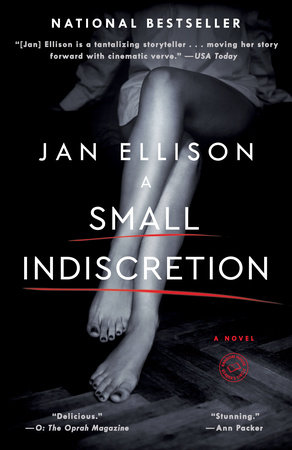

Jan Ellison’s debut novel, A Small Indiscretion, came out in paperback this spring. The book takes readers across decades and continents—from Berkeley to London and back again—to show us what happens to a happily married mother of three when the mistakes and youthful transgressions of years past unexpectedly turn up to meddle with the present. As with her O. Henry Prize-winning story, “The Company of Men,” Ellison demonstrates her ability to render without apology the not-so-nice sides of her characters, the imperfections and doubts that make them so recognizably human. We reached out to Ellison to talk to her about writing, unreliable narrators, and the term “literary suspense.”

Jan Ellison’s debut novel, A Small Indiscretion, came out in paperback this spring. The book takes readers across decades and continents—from Berkeley to London and back again—to show us what happens to a happily married mother of three when the mistakes and youthful transgressions of years past unexpectedly turn up to meddle with the present. As with her O. Henry Prize-winning story, “The Company of Men,” Ellison demonstrates her ability to render without apology the not-so-nice sides of her characters, the imperfections and doubts that make them so recognizably human. We reached out to Ellison to talk to her about writing, unreliable narrators, and the term “literary suspense.”

—

Rachel Howell: The book’s jacket describes the novel as “literary suspense,” which sounds like a punchier way to say “well-written page-turner.” It is somewhat rare, though, for a novel to be so largely character-driven while also being fueled by such a rich, suspenseful plot. Did you consciously set out to write a book that fell into this subgenre?

Jan Ellison: I don’t read suspense novels, and plot is not typically the most important criteria for me as a reader. I’m more interested in beautiful sentences and characters’ observations and an authentic voice. So it was a surprise to me when the first trade reviews came in and reviewers were using terms like “page-turner,” “emotional thriller,” and “psychological mystery” to describe the book. It would never have occurred to me to write a book described that way. But I suppose that when the various strands of the novel began to come together, I found that I was unconsciously dropping hints of what was to come and controlling the delivery of information. Sometimes I would find that I’d foreshadowed a thread of the novel before I’d written that thread, as if I were dropping hints for myself.

RH: The novel moves back and forth in time, between the distant past and the more recent events in Annie’s life. The structure is such an important component—not only in helping to build suspense, but as a way to reveal Annie’s character. Was the structure there from the beginning?

JE: Like the plot, the structure was late falling into place. I wrote the backstory and the present story somewhat separately, then tried to understand how they were intertwined in terms of plot, which would necessarily drive structure. I was juggling not two but three time strands—the distant past, the recent past, and the present, in which Annie is writing to her son as events unfold. It was difficult to figure out when the present narrative should begin, and how the recent past would catch up with the present thread and ultimately overtake it. There were months, maybe even years, when I didn’t think I was smart enough to finish this novel.

RH: One of things I love most about the novel is the way memory almost becomes a character itself. What Annie does, or does not remember, what she misremembers, even what she never committed to memory at all, all have grave implications for the choices she makes in the present. This makes her something of an unreliable narrator, as the best narrators often are, and yet she’s self-aware enough to recognize these shortcomings. “But maybe none of this is true,” she confesses at one point. How do you handle that delicate balance when writing a story like this, that is, expecting readers to believe Annie’s story when she can’t always trust it herself? Were you aware of this dichotomy as you were writing?

JE: With any book that narrates events in the distant past, this question of reliability is going to come up. If the fiction is to be lifelike, you have to deal with the nature of memory, which is not the same as the nature of experience. You experience something, you store it away as a memory, then you take the memory out—and that changes it. Not only that, but the interpretation of an experience changes as more life gets piled on top of it. I don’t interpret my own experiences in Europe at nineteen in the same way I did then. I don’t even interpret them in the way I did when I was forty and starting to write this book. With another decade of experience, and another decade of parenting—in which my eldest child has become the age I was then—things look a little different. The emotions I remember having had are influenced by the emotions I have now as I look back.

So, in a way, all narrators looking back are unreliable, just as people looking back are unreliable. Experiences are raw material; story-tellers shape that material. In a way, A Small Indiscretion is a novel about its material, but it’s also about its narrator shaping that material.

RH: In the introduction to a short story anthology I own, the editor writes, “We are a duplicitous people. On the one hand, we are quick to judge the sinners of indiscretion. On the other hand, we are attracted to the sin itself, and vicariously—through soap operas, sit-coms, novels, and short stories—we live our own lives chock-full of sexual impropriety.” Why do you think readers—and writers—are so frequently (and unabashedly) drawn to adulterous fiction? Do you believe we cut fictional characters more slack for all sorts of behaviors, and if so, why do you think this is?

JE: Fiction mimics life, and sexual impropriety happens not only in soap operas and sit-coms and novels, it happens in real life. I don’t know anyone who reaches middle age without knowing someone who has had an affair, or left one relationship for another one. Falling in love, or infatuation (is there really any difference in the beginning?) is the root of much of life’s drama, and so it is much of fiction’s drama.

JE: Fiction mimics life, and sexual impropriety happens not only in soap operas and sit-coms and novels, it happens in real life. I don’t know anyone who reaches middle age without knowing someone who has had an affair, or left one relationship for another one. Falling in love, or infatuation (is there really any difference in the beginning?) is the root of much of life’s drama, and so it is much of fiction’s drama.

Do people cut fictional characters more slack? I don’t think so. Many of the women I met in book clubs were terribly judgmental about my character’s actions, which surprised me. They wanted to know why I made her do certain things, why she was so unwise and careless. As a writer, I’m not in the business of making a character do something; I’m in the business of following her as she moves through time, learning to predict how she’ll behave in certain situations based on her past, and her temperament, and her emotional and psychological states. I don’t try to write what is moral or logical or wise for a character; I try to write what is authentic.

To me, spending time with my narrator, Annie Black, was like being with a friend who is setting off on a path of self-destruction. Judging that friend is not helpful. Standing by them while they go off the rails, and holding them up as they try to get back on track is helpful. It’s what I did with Annie Black, and it’s what I would do with a friend.

RH: A writing teacher once told me that I was too close to, or seemed too similar to, my main character, and that I needed to find a certain distance in order to find my voice. Your bio mentions that you are a mother of four, that you lived and worked in London in your early twenties, and that it was your notebooks from that time that would eventually become “the germ of A Small Indiscretion.” Annie is a mother of three, who also lived and worked in London after college. Without asking how much of the novel is autobiographical (I’m sure you get that enough), I am curious how much your own life, and past, informs your work, how you manage to keep that distance while very much writing what you know.

JE: In my experience, the distance is gained as the writing progresses. This is true for any particular piece of writing—a story, a novel, an essay, even a poem—and it is also true, perhaps, of a writing career.

I often begin with the low-hanging fruit: places I’ve lived, my own experiences, emotions, memories, observations, friends, family. Stories people tell me or that I read in the newspaper. Conversations I overhear in restaurants. That’s the raw material. And often, the initial attempt to get this material onto the page is done in a voice close to my own. But once I begin to shape the material into something resembling a story, the voice will necessarily be transformed. The narrator becomes not me but a character, the story is not my life but a collection of sentences deliberately, fictionally shaped to deliver an emotional truth that is typically not my own.

My first short story, “The Company of Men,” took me five years to write and publish; I probably wrote 100 drafts. The story borrows heavily from time I spent in Australia after college, both in its setting and in the events that unfold. The first impulse for the story came out of an exercise in a writing class. The first full draft was clunky, a kind of slice of life. The final story is very different, especially in terms of voice. Even though some of what happened to the narrator happened to me, the voice is not one I recognize as my own—it’s a voice that emerged in the service of the story over many years of revision.

RH: I want to ask you about that short story, which is just lovely and brilliant, by the way. “The Company of Men” begins with a middle-aged woman, Catherine, looking at a photograph, the only souvenir remaining from a time in her life she largely remembers with fondness. And yet, it is not by accident that this is the only tangible reminder of that time—she donated the rest before her marriage, explaining, “I wanted to be rid of so many failings, so many unhelpful habits and longings, when I believed the past could no longer inform me.”

Likewise, A Small Indiscretion begins with a photograph from the past, only this one has been anonymously sent to Annie, a woman in her forties who also appears to have put the past behind her. In both stories, the photograph is the catalyst that stirs up ancient history, bringing it to the foreground again. One notable difference is that Annie places the photo in a hatbox, the one that once held her wedding veil, and where she “keeps the important artifacts.” Is the overlap purely coincidental or do you find yourself drawn to these artifacts in your writing for a particular reason? Do you think writers, more than most people, believe that the past continues to inform? How compelled are you to hang on to (or let go of) your own physical reminders of the past?

JE: I didn’t realize that I’d used the photo motif in both my first short story and my first novel until a reader pointed it out. The photo in the short story is based on an actual photo; the one in the novel isn’t. But in both cases, the photos are physical representations of the narrator’s profound nostalgia.

I’ve often wondered if part of the reason writers write is that they suffer from an almost crippling nostalgia. I certainly do. When my children were small, I photographed them and took video of them, of course, but that wasn’t enough. I also kept a notebook, because I was afraid to lose track of the intensity of the emotional experience of becoming a mother. I was terrified that I would not be able to recapture it. That fear was justified, because I certainly can’t conjure the emotional tenor of their babyhoods any more without my journals.

I remember a neighbor telling me once that before he got married, he threw away every piece of correspondence from his old girlfriends, and every photograph of him with a woman who was not his wife. I was shocked, and horrified. To me, he was wiping out his own past. He was nullifying the experience that had made him who he was.

I’ve kept every notebook, every photograph, every letter I’ve ever received. I don’t spend a lot of time sitting around sifting through these artifacts, but I like to know they’re there.

RH: This is your first novel, but you’ve published several short stories in addition to the O. Henry Prize story. Do you consider yourself more of a novelist at heart? Or will you return to the short story form at some point? How does the process differ for you? Do you find one more challenging than the other?

JE: When I first started writing, I was sure I was a short-story writer. My stories were long, though, and I had to work hard to contain them. When I started writing what became A Small Indiscretion, I had a number of short stories completed, and a few published, so I though the thing to do was write a few more and put them together into a collection. How hard could that be?

It turned out to be impossible. I set out to write a coming-of-age short story set in London, and the pages kept coming, blowing past story-length, pausing briefly at novella length, and then continuing to accumulate until I had more than 400 pages of material with no end in sight. In five years of steady writing, I never got to the end of the story, never had a first draft.

Then I heard this sweet little story from another mom about forgiving her ex in-laws after holding a grudge for many years. I wanted to write it down. A year and a half later, I had 600 pages of material for a new novel, and I’d abandoned A Small Indiscretion. Then I sort of accidentally rediscovered it and within ten months, it was finished and sold to Random House.

RH: Who are the writers you most admire? What books are on your nightstand right now?

JE: Countless books have been important to me, too many to set down here. But there are not so many writers whose whole body of work I have read, sometimes more than once. These are mostly contemporary authors, since that’s what I’ve been reading for the last twenty years. To name a few: Ian McEwan, Alice Munro, Alice McDermott, Susanna Moore, Jane Hamilton, Margaret Atwood, Carol Shields, and I’m going to add Robin Black, a friend and author I deeply admire, whose work deserves to be widely read.

Right now I’m taking a bit of a fiction break and binging on memoirs. I just finished a gorgeous, heartbreaking, and ultimately hopeful memoir by Kay Redfield Jamison called An Unquiet Mind.

RH: What do your children think of your work? Have they read the book?

JE: My two eldest had the book in their rooms for several months, and every so often, I’d check their bookmarks, which never seemed to move past page thirty or so. My son said maybe it was a little too character-driven for him. My daughter reported that because she knows me, and she knows where my ideas come from, it kind of freaked her out. So I’m off the hook for now.

RH: I’m always interested in hearing about a writer’s process, when and where one writes, whether one types early drafts or writes longhand. Could you share a bit of yours?

My writing “process” is a bit frenetic. In the early phases of a project, it’s less about sitting down and making an orderly march toward a first draft than it is scribbling bits and pieces on yellow notepads, or into a word file on my computer, a catch-all for anything that might end up to be associated with the novel I’m working on.

I transcribe the writing from my scribbled notebooks into the word file, then at some point, when it’s 100 or 200 pages, I’ll stop to see what I’ve got and try to organize my material in a Scrivener file. Scrivener is a useful tool because you can see the manuscript, or in this case, the material for a manuscript, in outline form, and it’s easy to move things around. Once it’s all in there, I start moving toward a first draft. With A Small Indiscretion, by the time I had a first draft (seven years in), I was nearly done. This time around, I’m making more of an effort to drive forward to the end of the story before doing too much revision, but I’m not at all sure that effort will be successful.

When I’m generating new material, I try to do three hours a day, five days a week. When I’m editing, I try to get away from home for a few days and work twelve or fourteen hours a day until a revision is complete. I used to write in a café near my house, but now I’m lucky enough to rent a studio. It’s just a few minutes from my house, but the separation is helpful in taking me out of parenting-mode and into writing-mode.

RH: Are you working on anything right now?

JE: I was making good progress on my second novel, which is based on the 600 pages of material I generated when I took an eighteen-month break from writing A Small Indiscretion. It’s called The Safest City, and it’s set in Silicon Valley in 2011. It concerns itself with similar preoccupations as my first novel, but is very different structurally. It has several intimate third person narrators, some male, some female, and it doesn’t move back and forth in time.

Then in December, I arranged to get away for a few days to work on it, and left at the crack of dawn on Monday morning for our place in the mountains, where I often do my best writing. Half way there, I realized I didn’t have the right power cable for my new Mac. I veered off the freeway toward Modesto, home to the only Apple Store between me and the mountains. It was 8:30 in the morning. A security guard let me into the mall to use the bathroom, then I couldn’t find him to let me back out. I had ninety minutes to kill. I had my computer with me, so I sat down on a bench outside Forever 21.

Two women in tennis shoes and sweat pants were walking the mall, passing me again and again, so that I caught small snippets of their conversation as they made their morning loops. A short story occurred to me, and I thought I’d take a few notes. In the six months since then, I’ve written 150 pages of a third novel, provisionally titled The Mall Walkers, about a sixty-year-old woman, Patricia, who learns something horrible about her husband, gets in an RV and starts driving north in search of her adopted daughter, who has left home to find her birth mother. So far, Patricia’s gotten as far as—you guessed it—Modesto, where she finds herself in a shopping mall early in the morning, and things begin to get interesting.

It’s anybody’s guess which of these novels I’ll finish first.

Jan Ellison is the author of the debut novel, A Small Indiscretion, which was a San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of the Year. Recipient of an O. Henry Prize, her essays about writing and parenting have appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and elsewhere. A graduate of Stanford, Ellison lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband and their four children.

Assistant Editor Rachel Howell received her BA from Kenyon College and her MFA in Creative Writing from the low-residency program at Queens University of Charlotte. After ten years in Austin, she recently returned to her hometown of Nashville, where she lives with her husband and two young children. Her short fiction has appeared in the Atticus Review. Currently she is training herself to write amid the chaos and noise of full-time motherhood.