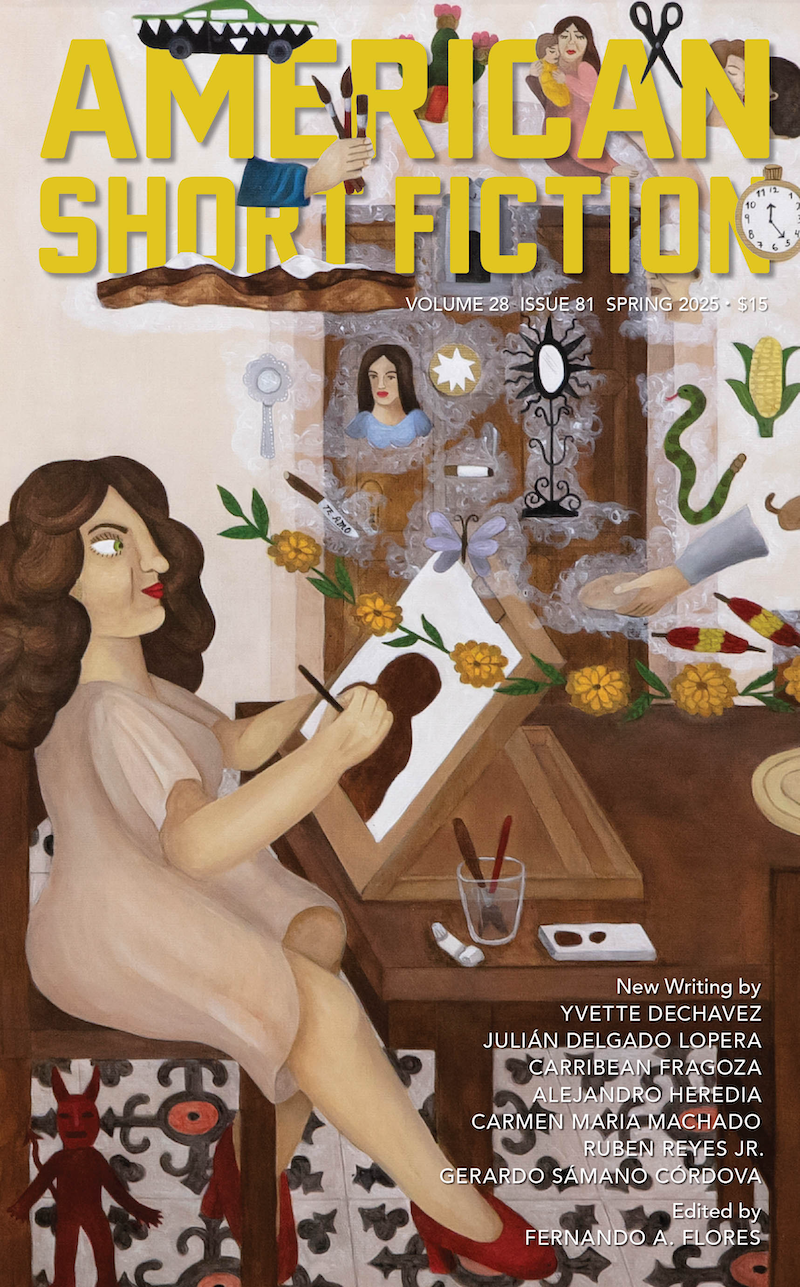

Guest-edited by Fernando A. Flores, featuring new stories by Yvette DeChavez, Julián Delgado Lopera, Carribean Fragoza, Alejandro Heredia, Carmen Maria Machado, Ruben Reyes Jr., and Gerardo Sámano Córdova.

I’d only hung out with Ana and Margarita a few times, and always with Rogelio, but I hated the way they talked, their eyes flitting back and forth between them like the mud-colored lizards hunting for flies in our yard. The two of them seemed to be in on a joke about life that I was too stupid to understand. But my mother was desperate to get me, her second daughter, married. I was twenty and husbandless, a bad look in my neighborhood in the Year of Our Lord 1970.

—

Goodbye, vida de mierda!

What you can’t see can’t touch you!

Welcome foggy green mountains crowned by gray cumulus. Welcome labyrinth of buildings desparramados death-dropping over the savana. Welcome top-hats, long coats, shiny shoes smoking cigarettes drinking all the tintos hailing all the taxis and giving zero fucks about Ignacio’s minuscule campo-turned-urban-boy existence. Welcome invisibility! How he’d missed that invisibility, muñeca. No cuchicheo gossipy gossip trailing behind. Everyone in Bogotá strutted down the streets like it was the end of the world and they were all late for it. No time to care about that body full of scars and bruises mapping the brutality of his campo upbringing. Hello, you’re in the capital, pollito, let the dreams come true.

—

Minnie knew her old friend would wiggle her way out of the situation, as usual would have everything under control. Minnie, on the other hand, was better off in no situation at all, for she never found an effective means to get a grip on things. Her mind was always spinning off, dreaming up images, landscapes, strange shapes. Her head floated like a tethered balloon above her body. Her mother used to say, “Minnie, the only reason you don’t lose your head is because its permanently attached to you.” But neither she nor Minnie had full certainty in that statement.

—

An hour later Emilio called to break up with me. It was true, he’d been distant for some time, but I still didn’t see it coming. I’d confronted him about it once, but he’d promised he was fine, just distracted as we all were by how slow and boring the end of the world seemed to be. Send me memes. Something chaotic, like you used to, I had asked, hoping the request would make him remember a better time between us. Before all this began, when we still laughed at the cruelty all around us.

—

It took me forty-five: teasing apart the pebbles of the shoulder blades with the flat on my index finger, kissing the scalpel to the fascia to release the skin, degloving the limbs, trimming the fat and flesh away with a pair of nail scissors. What an extraordinary thing, to see the skin alone—to worry it under running water like a washcloth, powder it as you would a baby. When I draped it over the form—stitching where the spine had been, pinning the face so it didn’t sit manically—it looked perfectly normal. That was the part that surprised me the most. How you could undo a creature so thoroughly and still bring it back together. Like your violence meant nothing at all.

—

Sometimes, the infractions were cut-and-dry, like the examples outlined during training. Ricky Maldonado posted throwback pictures of himself at Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby exhibition in Brooklyn. He was licking the sphinx’s pussy and honking her boobs. Reina hit the button and typed MISOGYNY. Cece Cortez coded a bot that catfished her former best friend using lines from Hugh Grant films. Reina typed IMPERSONATION. Clarence Le posted that he had sex with one of the married men running for city council, which was SPREADING RUMORS. (And, if true, SPILLING SECRETS.)

—

He wears a single-breasted suit, always indigo, pressed and spotless, which makes me think he has several of them, one for every day of the week, or more, in case of a backup at the dry cleaners. I wonder if he wears suits on weekends, away from our high-rise jobs. I can’t imagine him without his indigo single-breast, black shoes, white shirt, and silk tie. When I try, I only picture his exposed organs: a purplish beating heart, his ballooning lungs, bulging eyes, exposed teeth (perfectly crooked), and the fibers of his muscles wound tight enough to hold him upright. His clothes the container of who he is.

—

ASF Issue 81 Cover Art by Liz Hernández.

—

Yvette DeChavez, “Saint Gloria”

Yvette DeChavez, “Saint Gloria”