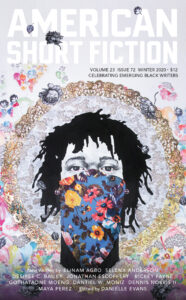

ASF is recognizing Black History Month by sharing, for the first time online, four stories from our Winter 2020 issue, which showcased emerging Black writers selected by guest editor and PEN American Robert W. Bingham Prize winner Danielle Evans. Here is author Denne Michele Norris, reflecting on the experience of writing this story:

I wrote “Audition” in a four week fury of inspiration during my first year living in New York City. It was a chaotic time, as first years in New York often are when you’re in your twenties. I was struggling to moor myself. But also, I was happy. Barack Obama had been re-elected. I had a part-time job that I loved at The Juilliard School, which paid my deeply discounted rent and allowed me time to write in the mornings. I was making friends, building a life. And I was slowly wading into the commitment of writing the novel from which this story is shaped. I understood that my character, Davis, would be with me as I grew up—he came to me ten years ago—and I also understood that the work of this novel would be to remain by his side as we, and our stories, grew up in tandem. Every day, stepping out of my apartment and heading to Lincoln Center from Park Slope, I felt wonderfully unmoored—like a country mouse who might be swept away in the endless energy of this larger-than-life city. Every day I hoped for that, and on many days, it happened. I didn’t know this then, but I wrote “Audition” because I wanted Davis to have the gift of catching a glimpse of his future—which was my future. And like mine, I wanted his father, The Reverend, to know that his child was going to be okay.

— Denne Michele Norris

—

It was crazy for the Reverend Doctor Preston McKinsey to think there was something sinister in the wind that day, but he felt it in the way it stung his cheeks—like a miniature slap to the face—and he saw it in the hardened pellets of sleet bouncing down the stairs as he entered the subway station. He walked behind his son, watching carefully as Davis negotiated the stairs and the turnstile with his cello. A memory arose: the long-held image of Davis at seven years old, marching through the tempestuous lake-effect snow on his way to grade school in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, his cello strapped to his back and his green Wellington boots almost reaching his knees. The Reverend wondered why he hadn’t driven Davis to school that day, though it was a mere two blocks from the house, a ten-minute walk even in the most inclement weather.

“Are you warm enough, Davis? It’s pretty windy and that jacket is thin.”

The Reverend unzipped his coat, unwrapped his scarf from around his neck, and presented it to his son. Davis ignored him. He moved away from his father, closer to the edge of the platform, his feet only steps from the yellow rubber that served as a warning to stay back.

“Davis,” the Reverend said. He was careful not to raise his voice.

As more people transferred from other trains, the platform became crowded. Instead of moving closer to Davis, the Reverend kept his eye on his son’s cello case, its outer shell the color of a ripe cherry. He watched as Davis peered down the tunnel looking for the lights that would signal the train’s arrival.

Perhaps Davis still needed space. He’d barely looked at his father in the last month, mostly staying in his room. He choreographed when to go to the kitchen or the bathroom in order to avoid an encounter. When there was one, he kept his eyes on the floor and stepped aside, careful not to touch, or be touched, by his father. At the last minute the Reverend had booked a flight to New York City, the idea of a cramped seat in coach more appealing than an eight-hour drive with his son seated next to him, petulance spitting from him at every turn. None of it was easy or went smoothly. When Davis wasn’t sulking, head down and hands in his pockets, he was a tightly wound bundle of stress. An invitation to audition at The Juilliard School had put him in a full-blown frenzy.

Davis was already rigorous with his musical training. He practiced scales, arpeggios, and etudes every morning before school and concertos and sonatas in the evenings. Recently, he’d been staying up late performing full run-throughs of the Elgar concerto and Bach’s third suite for solo cello, sometimes inviting neighbors or friends to sit nearby and listen. He was preparing for the start of audition season by building up stamina and working on managing his nerves. The Reverend could now sing every movement of the Bach. He was sick of Bach. And Davis was showing up to school unprepared. His calculus grade was plummeting. If he didn’t improve soon, his teacher warned, he’d be in danger of failing. The Reverend was frustrated: if Davis’s mother, Adina, were alive, she would be dealing with this.

The Reverend glanced at his watch. It wasn’t his first time in New York. He’d lived in Harlem for two weeks during a break from the Navy, drinking by day, sharing his bed with a different woman every night. This was before he’d been Saved, before he’d received his Call to the ministry. Before he’d married Adina, and before she’d gotten sick and gone home to the Lord.

There were so many people in this city, and it seemed that all of them were at this subway station, waiting for the train to come. Next to Davis was a group of twenty or so girls who looked to be around six or seven years old. They wore Catholic school uniforms patterned in green and black plaid, matching socks—white with lace circling the ankle—and black patent-leather Mary Janes. There were backpacks everywhere, slung over the backs of adults in jeans and Chuck Taylors. It was the middle of the day; he would’ve thought people would all be in suits, but that was not the case. And the smells—in New York there was always some disgusting odor snaking its way in and out of your nose, and the Reverend knew Davis wouldn’t appreciate it. This time the culprit was an old man wearing nothing but a pair of jeans—black, faded, stained with God-knows-what—and a torn gray sweatshirt that hung loose from one shoulder. His stench announced him before his sluggish, moaning presence did. As he moved, those closest to him shifted, so that the growing crowd appeared to be split in half, almost directly down the center of the platform. “I have a kind heart,” he kept saying, his voice as high-pitched as a child’s.

Davis and those near him stepped closer to the platform’s edge. The Reverend stepped in the opposite direction. It pained him to do so, to stick his hand in his pocket and fiddle with his phone, to avert his eyes like everyone else. He was a member of the clergy. He expected himself to live by a different, higher standard. He wanted to open his heart to the man. He wanted to give him money or food or a decent shirt. Mostly, he wanted Davis to see him in this way, to remember the kind of man his father strove to be.

This place is grim, the Reverend thought, and it trains you in its ways. And at eighteen, Davis’s existence was made entirely of moments—glimpses of joy and heartache and everything else. A young life was episodic; Davis’s understanding of the world relied heavily upon fumes—notions, impressions, ideas, and questions. What few experiences he’d lived were fleeting. The Reverend knew he deserved his son’s anger and, more than that, his disappointment. But it didn’t change the slow realization, as the Reverend stood watching, waiting, and listening, that Davis, though desperately wanting to be free of his father, simply wasn’t ready. He was bruised; by whose hand was of no importance. He had no business in a grim city like this.

It had only been a minute or two, but the crowd had thickened. Davis hadn’t moved, and the tip of the cello case was still visible. The Reverend watched it bob back and forth, just a fraction of a movement. He looked at the homeless man. He felt the wind whipping around his head, biting the tips of his ears.

He looked at his son. This city will eat you alive, he thought.

—

The Reverend often had to remind Davis to keep the curtains drawn over the sliding glass doors in the dining room. He was thinking of selling the house come fall, had recently installed new pine floors, and without care, sunlight could fade them quickly. On a particular morning nearly four weeks ago, the Reverend and Davis woke to the heavy rap of a rainstorm against the roof, no sun in sight. They scurried around the house, the Reverend preoccupied and Davis still half asleep. Davis absentmindedly opened the curtains on his way out, before rushing off to school, the Reverend already having gone to work. The sky was overcast; he wanted to let in some light.

That afternoon, the Reverend realized he’d left a file at the house. Since the church was out past the house, beyond Chagrin Falls, he stopped off at home, took a moment to catch his breath, before continuing on. After pulling into his immaculate black-topped semi-circle driveway, he parked behind Davis’s red Volkswagen Beetle. Deep down, he’d purchased the car for Davis because he’d liked its shiny red exterior, liked how it looked parked in front of their white Colonial, vibrantly green grass on one side of it, two rocking chairs and a jumbo checkers game on the other. When Davis parked it directly in front of the porch it was framed by the large white columns that had made the Reverend fall in love with the unassuming house their realtor had referred to as quietly pristine.

It was for moments like these that he had purchased a house that was so far removed from the actual city of Cleveland. Days when his head was filled with the arrogant foolishness of the pastors he worked with, men who were well-intentioned but didn’t always know, theologically, what they were talking about. Men who sought to lead others in their religious quests but stumbled privately, or sometimes not so privately. In tonight’s meeting, a committee representing their congregation would vote on whether or not to fire their pastor because of his blatant affair with a fat, boozy, single mother who’d been attending the church for a year and a half but never joined. Everyone, apparently, knew that the weekly offering she contributed was money he provided her with, and the way the Reverend saw it, things didn’t look hopeful.

Seated in his car, the engine still running, the black leather seats still heated, the Reverend found comfort in the picture before him: the fog rolling in from the hills, the grass, the shiny red Volkswagen, the perfectly paved driveway, and the disappearing remnant of sunlight that had been hanging just over the giant maple between their house and the next. He watched it appear, then flee, as though lifting narrowed eyes over the edge of a book, taking in the waiting world, and then deciding no, not today. For a moment there was an extra gleam about the Volkswagen, and he was filled with a sudden urge to see Davis, who by now would have eaten a quick snack and be seated in his room on the third floor, practicing for his auditions. The Reverend didn’t have to be at his meeting right away. He could stand at the door. He could listen as Davis practiced, repeating certain phrases and measures over and over and over again. He had nothing to do with the music, had done nothing other than support his son’s prodigious musical talent. But pride overcame him when Davis put bow

to instrument. Certainly it was sinful to take such pride in something as frivolous as his son’s abilities, but the Reverend was a man, a father. And a son, any kind of son, was a part of you in a way that no one else could be. God knew this, he believed, and understood.

He turned the car off, stood, and closed the door behind him as he stretched his legs. It was not easy anymore to sit comfortably in his car for a commute that was just over an hour each way. He bent forward, touched his toes, irritated when the hem of his suit jacket rolled up his back and flopped over his head. It was a lovely day, humid, warm enough that he thought perhaps spring had arrived a bit early. The morning’s rainstorm had left the grass extra green.

When he reached the stoop, he put his key in the door and took a deep breath before turning around. Over the hood of the Volkswagen he gazed at his front yard, then the gravel road attached to his driveway. Across the street was a large field, then a forest that stretched as far as he could see. Beyond that, towns and villages grew dense, eventually becoming the suburbs that neighbored Cleveland.

Whenever he came home and Davis was practicing, melodies greeted him through the door: at times the gregarious opening chords of the Elgar concerto, at other times the bleak softness of Shostakovich’s sonata. He listened, but today there was no music. Standing there with his hand on the key, he was astonished at the quietude of his own house, his surroundings. He turned around. Yes, there was the Volkswagen, so yes, Davis was home.

—

The homeless man stood in the center of the platform. Slowly, his feet moving inches at a time, he began to turn in a circle. He extended his arms, seemed to be addressing specific people when he asked, “Why are you moving? I don’t want you to move on my account.” His words, much like his feet, floundered; they were soaked in weariness. Sometimes he paused, turning his head to the left, or the right, or behind him. Occasionally he looked at the ceiling, as though some great and pleasurable secret were stowed somewhere in its polluted blackness. In these moments the Reverend thought the man looked like a wide-eyed, beaten-down rodent, something to be held tenderly in hand, doted upon, protected.

The Reverend suspected that he was the only person who saw the man this way. People kept moving. The nuns gathered close and spread their arms along the backs and shoulders of the schoolgirls, who paid them no mind. Half of them were laughing and dancing and playing games, and the other half of them stared faithfully, he saw, at Davis. A little red-haired girl, the smallest of the bunch, moved her head up and down as though in a trance, her eyes never leaving Davis’s cello case. Davis hadn’t noticed. He was focused on the tunnel as though

the intensity of his gaze might accelerate the train’s arrival.

The Reverend wondered if Davis was aware of the man—his presence, his words—but then he saw the white earbuds still tucked in his son’s ears. He was probably listening to Bach. He couldn’t hear the man calling for compassion.

“I don’t want you to move away from me. I don’t want to hurt anybody. I have a kind heart.”

At this point it almost sounded like a question, but he kept saying it as he turned in slow, methodical circles.

—

As he entered the house, the Reverend was thinking that perhaps Davis had listened to his teacher, Mrs. Sawyer, who encouraged him to ease up a little on the practicing. Davis wanted to peak during the auditions, not before them. And he wanted to leave something—some grain of spontaneity—to the music itself in order to keep performing it as a living, breathing thing. He was not a machine, she’d said, nor did he wish to sound like one.

In the front hall there was a massive wooden staircase leading to the second floor; above it, recessed lights. He turned them on. He moved to the family room, which was empty, as well as the kitchen behind it. Stillness reverberated throughout the house. He wondered if Davis had a plan for dinner. In the kitchen, under a magnet on the fridge, he left money for pizza. No need for a note, Davis would know what it was for.

He was filling a glass with water from the sink when he remembered that he’d left his notes on the dining room table. He took a drink and walked through the kitchen, his dress shoes clicking against the tile floor. He noticed a difference in the way the sound rebounded when he moved into the dining room with its new flooring. But the curtains weren’t drawn, and light beamed through the window. His hand against the table, his thumb sliding under the card stock bottom of the legal pad and his fingers curling around the edge, there it landed against his skin—sunlight beaming through a part in the clouds, straight over the valley like a slice of heaven, just for them.

It then occurred to the Reverend that he might find Davis out back, taking a break. There was a gazebo near the end of their property, down by the creek. In front of it was a birdbath. From childhood, it had been Davis’s favorite part of their home.

The Reverend opened the sliding glass door and stepped gingerly into the grass and the sprawling fog. As he cursed the early morning rain and the mud that would later line his shoes, he started walking to the gazebo. Davis had always loved reading outdoors on days like this. When he noticed another boy, a white boy—shirtless—standing upright in the gazebo, he stopped. The Reverend was close enough to notice the boy’s exposed skin, pale—almost red in some places. He studied the boy’s lengthy athletic frame, the baseball cap he wore backward, the loafers on his feet, and the jeans that were bunched around his ankles. He moved rhythmically, aggressively amid the thickening, unhurried mist.

It was Davis lying flat on his back on the bench inside the gazebo, legs apart and heels pointed skyward. The Reverend watched the boy move slowly over Davis’s body, saw those pale hips colliding against his son. He heard the boy grunt, he heard the boy breathe heavily. In the same moment, he heard Davis—the sounds he made delicate and airborne, flitting around the valley.

The Reverend tried to look away but couldn’t. He watched as the boy bent down and kissed his son’s hairless chest. He watched Davis arch his back, allowing the boy to slide his arm under it. The boy grunted again as he straddled the bench and pulled Davis upright, so that Davis was sitting on the boy’s lap, supported by the boy’s legs. And the boy’s hands were everywhere, moving all over his son’s body, as thoughDavis had been invaded—first around his waist, then at the nape of his neck, then gripping his arm.

The Reverend backed away toward the house. He removed one shoe at a time, then his socks, before stepping into the dining room. He walked barefoot through the hall and went upstairs to the master bedroom. In a corner of his closet, tucked underneath his ministerial robes, was a shoebox filled with black polish, cream, and several brushes. He grabbed the box and went downstairs. In the kitchen he started a kettle for tea but then thought better of it. He went to the dining room, opened the liquor cabinet, and poured a generous portion of whiskey into a tumbler. He went back to the kitchen for ice cubes and dropped them in the whiskey. When he returned to the dining room, he turned one of the upholstered dining chairs so it faced the sliding glass door and plunked it down with an authoritative thud.

He sat. He spread his legs and placed the shoebox on the floor between his feet. The whiskey went down like water. A fleeting thought: why didn’t he drink more often? The feeling wasn’t entirely unpleasant—like a marble rolling around in his head.

He opened the box and began to polish his shoes. No longer could he see Davis. No longer could he see what his son and that boy were up to, but he would watch their shapes emerge from the glistening fog that had settled around them.

—

A light rain came. The Reverend heard the boys before he saw them: Davis’s surprised shriek followed by his boisterously honest laughter—the kick he got out of himself! But it seemed the other boy did too. There was his laugh, sudden like a geyser shot from the ground, a booming mountainous laugh carried across the yard by its prominent bass. The Reverend rose from his seat. He stood at the window, inches from the glass, light shining upon him, tumbler in hand.

When he saw them walking together—his son’s hand gently sliding up and down the boy’s arm, his head nuzzled against the boy’s shoulder, the other boy smiling and talking and moving his own larger hand down Davis’s back—the Reverend felt something like a hand invade his chest. A fist gripped his heart. His arms went numb. Pain bolted through him and he bent at the waist, wondering if these might be his final moments. But the feeling passed, and in seconds he was right again—that startling sensation of seeing something that, on some level, he’d always known was true, coming to fruition.

He wished he’d missed the way the boys stepped from each other when their eyes landed on him standing in the glow of the dining room’s chandelier. He might have been looking at the grandfather clock, thinking it time he left for his meeting. He might have been focused on the whiskey, his eyes and lips tempted by the translucence of the ice cubes and the way the liquid caressed the tumbler. But he didn’t miss it, and from their faces, from Davis’s widened eyes and the other boy’s sheepish mouth that kept opening and closing with nothing to say, it was obvious they knew he’d seen their furtive movement.

The other boy, now wearing a faded blue T-shirt that stuck to his muscular chest, cocked his head to the side and grabbed Davis’s hand. He started to pull him toward the door. He stared the Reverend down, challenging him, determined—he was young and foolish and entitled. But Davis knew better; he pulled the other boy close, whispered in his ear. For a moment the boy fought him: he gestured emphatically at the house, at the Reverend, the intensifying rain darkening his hair and pasting it to his skin. This was a conversation, the Reverend realized, that had happened before. But Davis shook his head, no, and touched the boy’s chest, softly pushing him away. The boy took a deep breath. He looked out over the yard toward the gazebo. He lifted his gaze past the oak trees that lined the McKinseys’ property and the house that sat high on the hill beyond the creek.

The boy lifted his hands in the air as though admitting defeat. He turned and left along the side of the house. The Reverend remained where he was as Davis watched the boy leave. He studied the rise and fall of his son’s slumped shoulders, the defiant lift of the head he’d cradled in his arms when Davis was an infant, the cold cheekbones that appeared sharper in the rain and the burgeoning moonlight.

He stared at Davis. He’d never understood his son, but he understood himself, and it was best—he knew this—to back out of the dining room, whiskey bottle in hand, and turn off the light. He went upstairs and walked past his own bedroom. He wanted to be near Davis. He wanted to be as far away from him as possible. When he reached his son’s room, he walked around the bed. He passed the music stand and turned an open page. He passed the dresser, which held several vintage model cars, the kind he used to see on the road when he was a kid. He’d tried so hard with Davis to get him interested in cars.

The way he’d been when he was a boy.

He sat on his son’s bed, waiting for him to enter the house. He didn’t turn on the television or listen to music or open a book. He waited, listening as the raindrops thickened, as they began slapping the windows and the roof and streaming down the gutters. He listened until he heard the screen door, all the way down in the kitchen, close gently. Of course it closed gently. Davis did everything gently.

The stairs creaked. As Davis climbed them slowly, the Reverend continued to drink. He didn’t have to see his son to know when he arrived at the door.

“In here?” the Reverend asked. He kept his voice low and his eyes on the pillow, his words a statement more than a question.

Davis entered the room.

“I’m not telling you to come in. I’m asking if what I just saw happening has happened in this room.” The Reverend found the strength he needed to turn around and face his son. “In my house.”

Davis stared at him. “Dad,” he said. He put the palm of his hand out as if telling his father to back down.

The Reverend stood and raised his voice. “Has it happened in this house? Right here, in this bed?” He picked up the pillow and threw it on the floor. “This bed, that I paid for, in this house that I’m still paying for?”

He looked at Davis, who lowered his eyes to the ground.

“How many times have you allowed that boy to—”

“His name is Jake,” Davis said. The Reverend turned to face him once more. How child-like Davis looked. How ashamed, standing with his head down, backing into the doorway. But then he lifted his eyes. Slowly, clearly, carefully, he continued: “And we’re together.” He waited, then spoke again, more quietly, the whisper of a smile gracing his lips. “I have a boyfriend.”

For a moment, there was nothing. No sight, no sound, all senses erased. Until, from the Reverend, a single, simple, matter-of-fact demand. “You should go.”

But Davis didn’t move. He watched as his father turned back to the window, poured more whiskey into the tumbler, and lifted it to his lips.

Davis stepped into the room and sat on the edge of the bed. “This is my house, too. This is my room.”

“Boy, don’t test me.” The Reverend took another sip. “This is my house. You don’t pay for a Goddamned thing!” He slammed the tumbler down on the windowsill and wiped his upper lip with the sleeve of his shirt. Moments later, he was pulling Davis from the room and dragging him down the stairs. It was easy; Davis had always been small for his age. For a moment, the Reverend enjoyed his son’s fear. Then it broke his heart.

When they reached the foyer, the Reverend tried to speak, but there were no words, so he pushed his son out onto the front porch into the pouring rain. He shut the door behind him and waited a few minutes while Davis stood there, too scared to use his key to reenter the house. He listened as Davis pounded with his fists until he tired himself out. He listened as his son uttered a half-hearted “Fuck you” and walked down the steps and into the driveway. He waited while Davis opened, then closed his car door. Under the soft rumble of the Beetle’s engine, Davis’s words had seemingly imprinted themselves on his brain: “His name is Jake. And we’re together.”

—

It had become difficult to pick Davis out of the crowd, just that dash of red from the cello case, at certain moments invisible, at others staring back at him, steadfast and reliable, the smile of an old friend. A woman’s hair, piled high on her head like a bushel of wheat, blocked his line of vision. If he could only get a little closer to Davis, next to him, or behind him, even—if Davis would just allow him to do that . . .

But the platform was narrow and the crowd had grown dense. Space was tight, even surrounding the homeless man. The Reverend noticed that the man had stopped turning in circles.

Davis chose this moment to bend down and talk to the little Catholic schoolgirls that surrounded him. The small girl with the frizzy red hair poked and prodded him, and when he turned to her, she stuck her right thumb in her mouth and with her left first finger, she pointed at the cello case. The Reverend was surprised that Davis could crouch to his knees, making himself the same height as these grade-school girls, even with the cello on his back. He couldn’t hear what the girls said, but he imagined they were asking Davis what this giant thing was and why he carried it; what did it sound like, and could he maybe come to their school and give them a concert.

The homeless man was babbling now, impossible to understand—something about the military and a doctor. He seemed to be extending an arm behind him. He fingered the ripped collar of his sweatshirt.

The red-haired girl giggled. The Reverend watched as Davis brought himself to her ear, told her some kind of secret. He couldn’t see his son’s face, but he knew the sweet smile that was spreading over his lips. It killed him to think that if Davis remained as he was, he might never know fatherhood.

The man began pulling his sweatshirt over his head. To the right of his crooked spine was a scar that traveled all the way to the base of his neck, the skin raised, pinkish, cracked from drought. The keloid was lighter than the rest of him—his skin so black and rough it might have been charred. All the while, he spoke of his injury. With every movement he made, people squeezed closer together and farther from him.

An announcement came over the loudspeaker that an uptown local train was arriving momentarily. People pushed closer to the edge, happy for an excuse to distance themselves from the man, his stench, and his words. They hurriedly grouped according to which door they planned to enter. The Reverend was continually baffled by their knowledge of exactly where to stand, expecting the train’s doors to open right in front of them. Vague lines formed. Paths cleared. Three or four quick steps and he was standing behind Davis. The homeless man was headed their way, his eyes, seemingly, on the cello. The Reverend rested a hand on his son’s shoulder, but Davis stepped to the side—just an inch or so—and shook himself free.

Then the red-haired girl whose hand Davis had taken in his—the little one to whom he’d whispered something special—tumbled headfirst onto the subway tracks. For a moment she lay there, a pool of blood quickly forming where her head had smacked the metal rail.

The nuns screamed. The other girls screamed. And Davis turned to his father, his face like nothing the Reverend had ever seen because the train was now approaching, its horn blowing. Davis grabbed for his father’s arm, but the Reverend, in this moment a man unthinking, had already abandoned his son’s side.

On the tracks he crouched next to the girl and turned to look at the approaching train. Through the window he was able to make out the conductor who honked the horn, urged the brakes to work faster. At most he had fifteen seconds. He slipped one hand under the girl’s head and felt her blood spill into his palm and spread between his fingers. With his other hand he supported her calves. The train was close now; its turbulence shook him in his bones. He tried to lift the girl, but she wouldn’t move. Her laces were caught in the rail. The shoe was tight and there wasn’t enough time to pull her free. Part of him wanted to leave the girl and save himself. But she was awake now, and he saw immediately that her eyes were the same fossilized amber as Davis’s.

“Close your eyes,” he said, and she did.

The train blared its horn in short, emphatic bursts, and it didn’t seem to be slowing. “Get down!” he heard someone say, followed by many repetitions of “Down! Down! Get down!” He understood that the onlookers hoped the train might pass over him and the girl.

He flattened himself, the girl underneath him, between the rails, praying the space was deep enough, wide enough. But there wasn’t time to look. The tracks quaked. People screamed. The train sped toward them. He shivered. He prayed. And then there it was, its engine passing above him, its wheels screeching on either side of him, he and the girl facedown, buried deep in the fetid water that shook with the might of Goliath.

Denne Michele Norris is the editor-in-chief of Electric Literature. A 2021 Out100 Honoree, her writing has been supported by MacDowell, Tin House, VCCA, and the Kimbilio Center for African American Fiction, and appears in McSweeney’s, American Short Fiction, and The Undefeated. She co-hosts the critically acclaimed podcast Food 4 Thot, and is hard at work on her debut novel. Follow her on Twitter and IG @thedennemichele and visit her website at dennemichele.com

Denne Michele Norris is the editor-in-chief of Electric Literature. A 2021 Out100 Honoree, her writing has been supported by MacDowell, Tin House, VCCA, and the Kimbilio Center for African American Fiction, and appears in McSweeney’s, American Short Fiction, and The Undefeated. She co-hosts the critically acclaimed podcast Food 4 Thot, and is hard at work on her debut novel. Follow her on Twitter and IG @thedennemichele and visit her website at dennemichele.com

You can purchase a copy of ASF Issue 72, in which Norris’s story first appeared, in our online store.