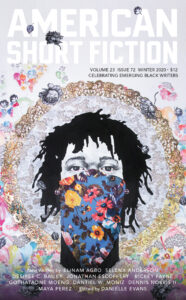

ASF is recognizing Black History Month by sharing, for the first time online, four stories from our Winter 2020 issue, which showcased emerging Black writers selected by guest editor and PEN American Robert W. Bingham Prize winner Danielle Evans. Here is author Rickey Fayne, reflecting on the experience of writing this story:

I began the story that became “Spare the Rod” as an assignment for a workshop led by Maya Perez (whose amazing story also appears in Issue 72). When I sat down to write, I had in mind a protagonist who was caught between failing at being a son and failing at being a father. As I followed him, I saw that his relationships with both his father and his son were haunted by the specter of white violence, turning love that should and could have been tenderness into seeming cruelty and callousness. When his father was in the army, white officers made him fight other black recruits. This experience embittered him, causing him to drink and casually neglect his children. When the protagonist was a teenager he and his brother were kidnapped and almost killed by a white neighbor in retaliation for a crime no one committed, making him cynically obsessed with self-defense. At the heart of this story is the question: is it possible for a person haunted by this type of violence to prepare their child to encounter it without reproducing it?

—

You can never just call up one ghost. You get one, and before you know it all the others are there listening in on everything you got to say. It’s like back when I was a boy, and the only kind of phone service folks out in the country could get was a party line. If you called one house on our street, you’d called them all. I can’t tell you how many times I picked up Ma’s rotary and ended up having to run out into the field behind Mr. Gibson’s to tell him his sister was on the phone, just for him to say, “Aw, Lula Jo don’t want nothing,” and go right on back to driving his mule, Apollo. Apollo was half blind and supposedly only kicked if you came at him from the left. Seemed to me, though, that he wanted to kick no matter which way you came at him. The day they shot Dr. King, Mr. Gibson was at the plow trying to wrangle just one more row from that hateful mule.

Anyway, that woman came to me again last night.

She sat down in the kitchen chair beside me soon as my son, James, went to his room, yellow dress and all, dripping a puddle under the seat. She comes every now and then, not wanting anything in particular, or so it seems, just to sit and enjoy my silence. She doesn’t talk and carry on the way some of the others do, not anymore anyway. I think mostly she comes around just to be seen. My wife, Catherine, was in Ripley visiting her folks, so I didn’t mind the company.

I was sitting up at the table trying to figure out what to do about James. He was getting picked on over at the school on account of those stitches running down the left side of his face. Truth be told it was a pretty bad cut. His momma treated it with honey, closed it with a threading needle and floss, and put some potato slices on it to bring the swelling down. It was as good as any doctor’s work I’ve seen, but when he went to school the next day the kids took to calling him Frankenstein. I told him he could sit out a while so as long as he made up his lessons. Sooner or later, though, he’d have to learn how to deal with people who didn’t like the look of him.

It had been a long day. I knew when I woke that it would be. The hogs got loose the night before, and running them down in the dark left me with a bone-deep aching in my legs. It’s fall and something in them can sense that pretty soon more than a few of them are going to be split down the middle, salted up, and smoked over coals.

—

Ma phones as soon as I finish getting my coffee creamed up with sugar, and before she can say what the trouble is, I hear Pa in the background tearing up shit, calling out for his pistol.

“I’m on my way,” I tell her.

I sit my coffee down, lace up my boots, and yell for James to stay put while I go to see about his grandparents.

The puddle is still under the chair where the woman had been. I make a mental note to mop it up before Catherine gets back.

When I pull up to my folk’s house—they don’t live but bout a mile or two down the road—they’re airing it all out in the front yard. Pa has given up on the pistol and settled for his rifle. Ma is on the porch in a blue housedress.

“Go on then,” she yells. “Go on and get yourself killed. I don’t give a good God damn if somebody puts a bullet in you.”

She has a black eye. Pa’s lip is bloody, so I figure he’s gotten just about as good as he’s given. I’d rough him up for it if I thought it’d make any kind of difference, but I know to my bones that it won’t.

“I’m gonna be the one what’s doing the shooting,” Pa says, laying the rifle down in the bed of his truck.

“Ain’t no use in you trying to stop me,” he says.

“I’m not here to stop you,” I tell him. “I’m here to help you do it.” Funny as it seems, it helps for him to hear the opposite of what he’s expecting.

He whips around to face me.

“You do what now?”

“I said I want to help you do it.”

By then Benny pulls up. I’d passed him on the road and waved for him to turn around and follow me. Benny and me went to school together, and he has a sort of calming effect on Pa. His uncle, Junior Ross, served with Pa in the war, only Junior never made it back.

“You don’t really want to hurt nobody do you, Mr. Louis?” Benny says, getting out of his truck. He has on a rumpled Ross family reunion shirt and flea market jeans.

“It ain’t about what I want, Benny,” Pa says. “It’s about what needs doing.”

Pa gets like this every once in a while. He drinks away half the night and wakes up the next morning thinking somebody has done him wrong and wanting revenge. Usually it’s some slight that happened long before I was born, back when Pa was younger, meaner too if you can believe it. I can’t. He drunk-dreams it all back up to where he can’t tell the dream from the truth. There’s no making him see that it’s all just a memory floating up, that the person in the dream has already passed on and it was only their ghost paying him a visit.

The dead come for all kinds of reasons. They come with warnings, wants, and every manner of grudge. Though most I’ve seen come wanting. They come wanting everything you have and can’t give.

Some of the ones that come to Pa are soldiers from across the waters. They come trying to figure what happened and why. Why did they have to die and what was it all for? He tries to tell them that he doesn’t understand it any better than they do, but they don’t believe him. If he’s living and they’re dead, he’s got to know something, don’t he? He never actually gets to where he can hurt anybody, most times because there’s nobody living to hurt, but it’s right worrisome for him to ride around with a loaded gun in his lap.

Between Benny’s truck and mine blocking him in, there is no way for him to back out of the driveway. It’s rare for him to try and make it by us on foot, and I am hoping we can get him calmed down before we have to worry about that.

“Y’all boys go on home now,” he says, patting down his coverall pockets, searching for his keys. “This ain’t got nothing to do with either of you.”

Him knowing Benny is a good sign. If he was still in his dreaming mind, he wouldn’t recognize anybody outside of me and Ma. It usually means that he’s snapping out of it. But sometimes it takes him a little longer, and he knows his surroundings just well enough to make trouble. It’s faster if you can get him talking out what all he thinks happened to him, to get it out of his head and into the world. Otherwise it could take all day. Used to be he could work it out for himself. It’s only in the past few years, after he handed the working of the land over to me, that he’s gotten to where he wants to be outside and violent.

He turns to me. I can tell from the narrowing of his eyes that things are going the other way. The part of him that knows me is gone. Benny closes the door to his Dodge and walks around back of Pa’s Chevy. He sees what I see. We have to get him to the ground and it won’t be easy. Pa’s old but he’s every bit as strong as I am, stronger when he’s out of his mind. Luckily, he makes for me before he thinks to reach for the rifle. I plant my feet and hunker down. He lowers his head. Tries to run. He can come, but I won’t let him past me. Before he can, Benny grabs him from behind and picks him up. Pa kicks his feet out. I grab his legs. This is how we get Pa back in the house.

—

I started seeing the woman in yellow when I was just a boy. I’d wake up and peep out from under the covers, and there she would be rocking in the chair by the window calm and cool as all get out, rocking and smiling, rocking and smiling. The first time I just put those covers right back over my eyes and acted like that old rocker wasn’t creaking away until dawn. When I finally took notion to leave the bed, the afghan draped over the chair had soaked through and was damp to the touch. At breakfast Pa asked me how I had slept. I said fine. He said it didn’t look like it. I tried to get on with the business of the day, but nothing I swallowed went down right.

—

We wrestle him onto the couch, managing to Ma’s relief not to break the marble coffee table she’d had shipped from Memphis back when she thought her life was going to be bigger than what it was. Pa recognizes us so he doesn’t fight as hard once we get him down, but he don’t make it easy to keep him there either. It seems to me that now he’s fighting us more out of spite for being manhandled than anything else. After a tussle, we make him understand that we won’t leave until he calms himself.

This is how days like this usually go. Pa gets angry, then starts to feeling bad and wanting to make nice with everybody in listening distance. But it’s not long before he resents everyone he felt he had to apologize to, sorrier for himself than anybody else, and takes to drinking again.

Ma gets her overnight bag, and I walk her out to her car. I maneuver it into the grass around Benny’s truck and tell her that she doesn’t have to stay here if she doesn’t want to. I tell her that Benny and me can get her stuff together and bring it to her sister’s house if she wants. She puts her bag in the passenger seat.

“I’ll be back tomorrow,” she says.

Inside, Benny is standing over Pa and Pa is staring up at him. I smell something burning, and in the kitchen I find a skillet of half-fried eggs on the stove and a cast-iron of smoking black biscuits in the oven. He couldn’t even let her get through breakfast.

I tell Pa that I don’t want no apology. What I want from him is to talk out what all he saw right here, right now, so that maybe he won’t go to sleep with it worrying him and call up whatever ghost put murder on his mind.

“Mr. Louis,” Benny says. “What he do to make you want to hurt him so?”

Pa looks over at Benny, then down.

He’s calm now, but the anger has yet to leave his eyes. Benny looks at the pictures of Ma and her side of the family before taking a seat in the red wingback chair across from the couch. He can tell that Pa’s fixing to tell a long one. I stay standing.

“I ever tell you how I know your people?” Pa says to Benny.

Benny shakes his head no before I can catch his eye.

Pa starts in on some story about Benny’s great-grandfather Franklin casting off the yoke of slavery with both arms, picking the name Ross up off a gravestone because he liked the curve of the letters, working his way out of tenancy a generation before anybody else. I’d heard these stories a thousand times, how Junior was killed in an ambush, how the bank took what was left of the Rosses’ land from Junior’s father before he had a chance to show the papers to somebody literate, how much better off the Rosses would be if Junior had been around to manage things.

“What’s this got do with anything?” I ask.

“It’s got everything to do with it,” Pa says. “If it wasn’t for your great-grandpa Franklin,” he says turning to Benny, “everything would’ve ended up in the hands of the white folks.”

“Pa, we’ve heard all this.”

“I haven’t,” Benny says, and I realize that he might not have. Benny’s momma is kind of funny acting. I’ve known Miss Ross all my life, but when I see her out—when I try to speak—she looks right through me like she doesn’t even know my name. At first I thought it had something to do with Pa and whatever it was they had going way back when, but it’s not just me she turns her nose up at. There’s no telling what she has or hasn’t told Benny about Junior, or anything else for that matter.

“Anyway, when the war broke out, Junior’s number came up first, but folks barely had time to make peace with that before mine was called.”

I walk over to the window and peep out at the yard.

“My father drove us to Memphis so we could catch the bus to Atlanta for basic training. Ma had packed me a suitcase and a cooler full of chicken and corn pone. Junior Ross got in the truck with nothing but the clothes on his back, saying he figured they’d give him what all he needed when he got there. I knew then why Ma had packed my cooler so full.”

Outside, Pa’s dog is barking up a storm. I look around the yard, but I don’t see anything that would make him carry on the way he’s doing. It’s only after I take my attention away from the dog that Pa finds his way around to making some sort of point.

“I say all this to say that our families go back a long way, so it does me good to see the two of you getting along. The man I need to kill he, he took someone from me. He killed my best friend and your uncle,” he says, turning to Benny. “Junior would have been proud of you, Benny. You take after him in more ways than one.”

Pa turns to me, and his eyes tell me all the words his mouth ain’t saying. He’s his self again. I walk back over and stand beside Benny’s chair.

“Benny,” Pa says, “your uncle didn’t die at the hands of no Korean like they told your momma. He was killed by an American, a white boy named Jeb.”

“So that’s who come to you?” I say. “The ghost of the man who killed Junior Ross?”

“No,” Pa says. “Jeb ain’t no ghost.”

—

The woman in yellow came regular each night after the first. Early on she was silent, content to sit in Grandma’s old chair and rock and knit and hum like I was a visitor to be tolerated but not considered. Then one night she said, more to herself than to me it seemed, that my room used to be her room. But it wasn’t hers. It was mine and she was all right with it. It took her a while to be all right, but she was now.

I peeked out from under the covers and asked her if she was living or dead.

She said she hadn’t thought about it recently, but the last time she checked she was dead. Though sometimes she forgot and it seemed like she was alive.

I asked her how she died.

She said she’d rather not say, but if I really wanted to know, she would tell me.

I told her that she didn’t have to tell me if she didn’t want.

She said something about the sky, but I couldn’t make it out.

“Robert, who you talking to in there?” Ma had asked.

“Nobody.”

“Don’t sound like nobody.”

Ma walked in and the woman put her finger to her lips.

“Myself.”

She studied the room like she didn’t believe me but couldn’t find the right reason not to.

“You’re not nobody,” she said, finally. “You hear me?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Good. Now go to sleep. It’s late.”

“Drowning is one thing,” the woman said after Ma left, “but to have the sky enter you is another thing altogether. You look right up into that blue and you feel like you’re falling, but you ain’t. The sky is the one doing the falling. It’s the one making its way into you. That’s how I passed on. I let the sky in to have its way with me and then I couldn’t figure what was me and what was it. I couldn’t find my way back to the ground fast enough to keep myself from falling, and before I knew it the ground was coming up to meet me.”

“What do you mean the ground came up to meet you?”

“I mean just what I said. The ground can be a loving thing from the right distance, but it can get to be right hateful when you’re looking at it from faraway and too close.”

She didn’t say anything else that night. She just kept rocking away in that chair with her hands in her lap. I couldn’t get to sleep for fear of the ground coming up to meet me one day.

“Your momma thinks you were talking to yourself,” Pa said.

It was the next morning, a Saturday, and I was slopping the hogs while he was standing there watching me do it. He claimed to be getting a feel for what all the weather would allow us to do to the field. Said that the day had to have a certain look before you could seed.

“It wasn’t nobody there. I was just making conversation with myself.”

“That so?”

“Yeah,” I said.

The hogs were in a pen behind the house. After I finished up with them, there was a pregnant cow out to pasture that Pa had a mind to check on. If she was ready, he was going to teach me how to birth her, and all I could think then was how much I didn’t want to learn.

“They come to me too,” he said. “They don’t come to your momma or your cousins. They don’t come to your uncle or your grandpa or anybody else you might meet, but they sure as shit come to me.”

—

We take my truck because it has the most room and I’m the only one who bothers to keep the registration up. Pa is up front with me, Benny’s in back with the woman in yellow. The water from her dress is soaking into the seat, dripping down to the floor, washing the floorboard, and wetting my boots.

The question I want to ask but can’t seem to find my way around to is: why now? For thirty years, Pa has suffered this man to draw breath. What I don’t have to ask is how much of a mess of things Pa might make if I don’t keep an eye on him. Last time, after wrestling with him half the day, after thinking we’d finally put it all to bed, he slipped off. I’d barely had time to get home and get my boots off before Eva Watson called the house saying she’d seen Pa drive by—rifle hanging halfway out the passenger side window like an old bluetick—just before she heard a shot. By the time I caught up to him, he was at Buck Rogers’ old place sitting on the rotted-out porch looking lost. I hid his guns after that, but he just went out and bought new ones.

“It was Junior come to me,” Pa says. “It was Junior that came to me in the night. I hadn’t thought about Jeb in a good long while, but when Junior come to me he reminded me that it wasn’t my grudge to forgive.”

“You have to do it now, though? Why don’t you take a couple of days to think it out?”

“It’s gotta happen today,” Pa says.

It’s a three-hour drive to Dyersburg, two if we take the new highway but Pa would rather the back roads. After about an hour, I need gas and Benny says he’s hungry, so we stop over at a gas station in Henning. I fill up and Benny gets back in the car with a greasy brown bag full of fried chicken livers. Across from the station there’s a sign advertising the W. E. Palmer House Museum. We get back on the road.

—

You see them first out of the corner of your eye, a shadow flitting its way across a well-lit room, a stain on the carpet that won’t never get clean, a too-warm spot beside you in the bed. You blink and they’re there, as live-seeming and whole as any person you’d want to meet. They come to loved ones if their loved ones can see them, but if their loved ones can’t, they come to anybody who can. If you’re lucky, you’ll blink again and they’ll be gone just like they never was. But if you’re like me, if you’re like Pa, they never leave.

“It takes a good while to get used to,” Pa had said. “But after a time seeing them won’t bother you no more than a mosquito. You might even learn a thing or two if you listen good.”

We were watching the Cardinals play the Cubs. Ma had gone into the bedroom to read because she didn’t, and never would, trust the television. The news was just about the only thing you could get her to sit still for. This was back when Ma worked the line at World Color, before she quit because the ink had started to dull her sense of smell and her hands were stained a rich light green that wouldn’t go away. When I was small, I wanted to work at World Color, too, so that my hands could be green like hers.

“I was five when they first come to me,” Pa went on. “I couldn’t tell no difference between them and living folks and caught hell for it.” Pa was in his favorite chair. I was on the floor. This was before he started drinking himself dumb, barely making it home before dawn.

“You’re lucky,” he said. “You got most of your growing up out of the way before they come to you.”

I didn’t feel lucky.

—

Besides cotton, there’s not all that much to see between here and Dyersburg. Every once in a while something new gets built up, a restaurant, a bar, a bowling alley, but you can pretty much set your calendar to its closing. The only thing I’ve ever seen that has any staying power, outside of the gas stations, is McDonald’s. And for every one that crops up like ragweed, there’s some place good that goes under.

Benny is staring out the window and starting to get antsy. Fiddling with the funeral programs in the pocket behind the pas-senger’s seat. I never planned on putting them there, but after each funeral I reach around and slide the program in. I don’t know what I would do with them if they ever made it into the house. Through the rearview mirror, I can see that he’s bending the front cover of Mr. Gibson’s program back, then watching it spring forward. It shouldn’t bother me but it does.

Mr. Gibson died peaceful, in his sleep. When he comes, it’s always through the front door with his hat in his hand, offering me a handful of molasses candy in exchange for snapping a bucket of peas just like he did when I was a boy.

—

I don’t remember Benny saying one way or the other whether he wanted to ride with us or not, but he’s here, so the choice was made with his body if not his mind.

Pa’s sitting eyes front, stone still.

“Keep straight,” Pa says.

“I’m keeping straight.”

“No, you’re not. You’re wobbling. You’re all over the paint.”

The sun is just making it up over the line that separates tree from sky. When I was younger you could hardly see the sky for all the over-growth, but ever since Clayton Cotton bought up all the land on either side of Hwy 14, clearing out every green thing that refused to grow a coarse white boll, it’s gotten bigger and bigger, and today there’s not a cloud in it.

“You’re going to want to turn off here and take 70 the rest of the way,” Pa says.

“14 will take us all the way to Dyersburg,” I say.

“Not to his neck of it.”

I make the turn and it puts us directly in the path of the sun, and part of me wonders if it wouldn’t have been better to make this trip under the cover of night.

“Daytime’s better,” Pa says, reading my face.

I don’t ask why.

Pa never spoke of his time in the army when I was coming up, except to say I should never join. By the time I came of age the war in Vietnam was over, and the only folks that went into the military were the ones who couldn’t find a job or didn’t have any other way to pay for school, praying all the while that a war never broke out. Pa never had a choice. Neither did Junior Ross.

“Y’all are good boys,” Pa says. “Nobody could ask for better boys.”

Benny’s eyes meet mine in the rearview.

“Y’all know what I mean,” Pa says, turning toward the window.

Driving through Jackson reminds me of the few years I’d spent here as a student. College was fun until it wasn’t. Going to that school gave me Catherine but not much else.

“I shouldn’t be dragging y’all into this,” Pa says. “Y’all don’t have no place in it. Just drop me off down the road and I’ll figure it out. You won’t have to be there. You can just park a ways off and I’ll find you. You don’t have to be there for anything.”

“Mr. Louis, we not letting you do this alone.”

“You won’t have to do anything,” Pa says. “Just leave it to me.”

“How you want to kill him?” Benny asks.

“The same way he killed Junior,” Pa says. “Just the same way.”

He doesn’t say what that way is.

After another hour, we turn off the highway on to a side road. Benny leaves the programs alone and starts flipping his armrest up and down, and the woman in yellow is watching him like she’s never seen anything like it. Pa is bout sleep.

“I’m awake. Just resting my eyes.”

“Nobody said you weren’t.”

“I could feel you staring at me. You should be watching the road.”

“I’m watching the road.”

“Could have fooled me.”

I don’t give him the satisfaction of a response.

“Turn here,” Pa says.

I turn, and in another mile or so we reach Dyersburg proper. It’s been years since I had a good reason to drive up this way, and I notice that a lot of new things have sprung up alongside the old. Chain restaurants and strip malls pave our way forward.

“Now if we really gonna do this,” Benny says, “we need a plan.”

Pa nods.

“The way I see it, we got a few ways to get this done. We can leave him where he lays, take a few things and make it seem like a robbery. Another way to go would be to make it look like he did himself in. Make him swallow some pills and lay him out on his bed all nice and neat. Or we could bring the body with us and take care of him at home. If we do that it gives us a little bit more time before folks start looking at it funny. Of course that means some liability on the backend, but I’d much rather that than waiting around to make sure the police see things how we need them to. But I think with us being from out of town and all that we can get this done nice and quiet with nobody looking at us sideways.”

Pa turns around to face Benny, then cuts his eyes at me. He cuts his eyes at me because he doesn’t know what I know. He doesn’t know that Jeb won’t be the first white man that Benny and me have killed.

—

It was my sophomore year of high school and Candy Smith, a white woman not too much older than Benny and me, got caught with a man her husband thought might be Black. Before she married, Candy was a Laurent, and being a white Laurent still meant something to some people, even though her branch of the family had only known hard times. Her husband, Ken, was one of those people. His father delivered milk for Laurent’s Dairy for thirty years, and Ken’s first paying job, along with damn near every other white boy in the county, was at Laurent Farms picking strawberries. So when Candy Laurent agreed to go with him to the drive-in and then, a year later, to be his wife, Ken—a high school dropout who used his brother’s license to get a job as a long-haul trucker—could hardly believe his good fortune.

Everybody in town knew that Candy kept a boyfriend or two while Ken was out on the road, but nobody ever felt it was their place to say so. When Ken pulled up thinking, knowing, how nice a surprise it would be to Candy for him to arrive a day early, he saw a man walk right out of his front door, glance at him, and then take off into the woods. The first thing Candy thought to say was that someone had broken in and tried to have his way with her.

Ken called Sheriff Potts that very night, and the next morning Sheriff Potts, his deputies, and a band of overzealous volunteers—the likes of which are never in short supply—invited every colored they didn’t like the look of down to the station. But when it came time to pick one of us out to punish, Candy came clean and Sheriff Potts, shaking his head the whole while, let us all go.

Only Ken didn’t let it go. Even after Candy had laid the truth of it out and told him all about her boyfriends and how she met most of them at the diner she waitressed at, and how she loved Ken, loved only him, just lonesome was all, he couldn’t let it go. He’d fixed it in his mind that a nigger had run up in his house and tried to take what was his.

“Candy just a good-hearted woman,” Ken said to us the next week out in the woods.

Benny and me were walking back home from basketball practice when Ken called out to us from the road. I wasn’t any good, but anybody who’d seen Benny play knew that he might have a future in it, so white folks were always going out of their way to talk to him so that if he got famous, they could tell folks they knew him when. I figured Ken wanted to say something to Benny about basketball or to ask me after some work, since between hauls he sometimes helped out around the farm for a little extra money. Pulling a gun and walking us into the woods was the last thing I expected him to do. By then, Benny and me had put all that foolishness with Candy behind us. You can’t carry everything with you.

“Too good-hearted even to see justice. Too good-hearted for her own good. But you niggers know what’s what, don’t you? You know that justice ought to be served.”

Benny and me just looked at him.

“Yeah, I believe it was you I seen running that night. Yeah, you the light one,” he said, pointing to me with his pistol. “I thought it was an awful pale nigger. Maybe that awful pale nigger was you.”

“You got anything to say for yourself,” Ken said, water thickening to tears in his eyes. “You know what it’s like to go out and work for some-thing. Hmm? No, no you don’t. You niggers got it easy. Got everything handed to you. Especially, you.”

He was talking about me. Pa’s family had always had land, and poor white folks, especially those coming up from Memphis trying to find a cheaper way to live, resented it. That he was alone and carrying a pistol was a comfort. I’d seen Black folks die in ways much more painful and public.

“Good white folks out there working like dogs and here you got everything handed to you. It’s a damn shame.”

“Mr. Ken,” Benny said. “Ain’t nobody out here touched your wife but you.”

“Ain’t nobody out here asked you to put your goddamned two cents in either.”

Benny put his hands down and took a step toward Ken. The leaves were dry enough for you to hear each foot fall. We were in a clearing just shy of Pa’s property line. Not a month before Pa and I were down here breaking up a whiskey still. Nobody was foolish enough to hide one on their own land, but a law came down that the sheriff could arrest anyone within a hundred feet of a working still, so if you came across one, especially as close as this one was to the cow pasture, you pretty much had to bust it up. If one of the hogs hadn’t have gotten out, caught the scent—there wasn’t much hogs loved more than sweet corn mash—and led us to it, we might never have seen it. My ears were just past ringing with the sound of axes striking metal.

“Ken, if you gonna shoot us then go on and shoot us, but I ain’t gonna stand out here in the sun all day catching your spit.”

I put my hands down. I saw what Benny saw. Ken either forgot or didn’t realize he’d left the safety on. Benny speared him. He drove his head into Ken’s gut and took him to the ground. Ken dropped the gun, and while Benny was laying into him, I picked it up and flicked the safety off. But before I could think about whether or not I wanted to pull the trigger, whether or not I had in me what Pa has in him, I heard a crack and felt the gun recoil. Benny stood, breathing hard and heavy, and Ken, he was lying flat, eyes open, arms out like it was a white Christmas and he was about to make himself a snow angel. He was staring up at me like he wanted someone to watch him do it. When Ken’s ghost comes, when he lays himself out on the carpet, when he plants himself in front of the wheels of my truck, he looks up at me just like this.

—

We pull up to Jeb’s house near about noon. It’s a good ways from downtown, and his closest neighbor, from what I can tell, lives two miles up the road. We park behind a stand of live oaks and track how many cars drive by. In the span of half an hour we see one. We work out that Benny is going to go up to the house first. He’s going to knock on the door to make sure Jeb is home and no one else. He’s going to say he’s got car trouble and needs to use the phone. If Jeb’s a good Christian, he’ll let him. If he knows his way around an engine, he might even offer to take a gander.

“There’s things you need to know,” Pa says once Benny’s gone. “There’s things you need to know that I haven’t found a way to say.”

The woman in yellow used to want things. She wanted things that no one living could give her. That’s what Pa’s voice sounds like to me now. Like he needs something that no one living can give him. She’s with us in the truck, staring out the side of the window nodding her head to whatever song it is she’s humming out. The notes edge toward something familiar but never quite seem to make it there. If I didn’t know any better, I’d think she was doing it just to get on my nerves.

“I know,” I tell him before he can get it out.

“Naw,” Pa says. “There things I done that I’m not proud of . . . People I haven’t done right by . . .”

“I know,” I say.

Pa lets out a loud sigh and turns toward Jeb’s house. From the driver’s seat all I can see is trees and brush. Mostly live oaks and scrub, but on the other side of the ditch I notice blackberry brambles. My son, James, won’t eat fresh blackberries but he’ll eat them in a cobbler. I asked him why once when we were sitting down to a cobbler his mother made, and he told me he didn’t like the seeds. I told him that they still had seeds in the cobbler. But when I said this he just shrugged and went back to eating.

“What’s your wife up to today?” Pa asks.

“She’s out visiting some of her folks.”

“She does that a lot,” he says.

I don’t say anything to that.

Benny makes his way back to the truck. He’s eating something, but it’s wrapped up in a napkin so I can’t tell what it is.

“He in there,” Benny says, chewing. “Don’t seem like he’s expecting anybody anytime soon.”

“What are you eating?”

“Biscuit and bacon,” Benny says, and as he says it a piece of bacon falls out of his mouth and onto the ground. Seeing it makes me think of how fat Benny’s dog Tyson is. There’s probably people who don’t eat half as much as what that dog picks up off the floor.

“He made you a sandwich?” I ask.

“Yeah,” Benny says.

“What of it?” I don’t know what to say to that.

“How did he seem?” Pa asks.

“He seemed like an old white man,” Benny says.

Pa turns toward the house again. I crane my neck to get a better angle, and I can see it now. It’s nice but not too nice, set a ways off from the road. If nobody does anything about the trees, in a few years’ time you won’t be able to see it at all.

“I told him I had to lock up,” Benny goes on. “He’s in the house waiting.”

Pa gets out the truck and walks around to where Benny is.

“You boys don’t have to do this,” Pa says. “I can go in alone.”

“Is that what you want?” I ask.

Pa nods.

Benny claps Pa on the shoulder and walks around to the passenger side. He’s still eating. I try not to think about how I’m going to be the one digging the crumbs out of the seat cushion when we get back. Pa starts up the driveway, glances back at us, and keeps walking. He’s not carrying his gun, but I can tell that he’s got something up his sleeve. He seems different from this morning, though. Benny brushes off his pants, sticks the napkin in the cup holder, and asks about turning on the radio, but music on top of the woman in yellow’s humming would be too much for me, so I tell him no.

—

Pa told me once that ghosts don’t care anything about time. All that matters to them are the things that happened to them. It don’t matter to them how long ago it was.

“Let’s go watch,” Benny says to me.

We walk around the side of Jeb’s property, making our way through the brush and blackberry brambles. The berries stain Benny’s shirt like dried blood as we wade through them. I try to be more careful.

Around the side of the house, there’s a window that allows us to peep into the living room. Jeb is smaller and weaker than I’d imagined. He’s wearing a green flannel shirt tucked into a pair of pleated slacks. He must be a few years older than Pa.

Jeb is sitting there watching Pa pace back and forth. They’re talking. I can’t imagine what about.

“What they jawing about?

“I don’t know.”

Pa sits down on the couch beside Jeb, leans forward, and looks down at his hands like he’s frightened at the sight of them. Jeb puts his hand on Pa’s back. Benny asks me again what they’re doing. I tell him that I know just as much as he does.

Pa turns to the window. He sees Benny and me and makes to stand up. Benny starts walking around to the front and I follow him. Pa meets us at the door like it’s his house and we haven’t been invited.

“Jeb is a good man,” Pa says. “I just got a little mixed up is all.”

“These your boys?” Jeb asks, standing up. There’s an expression on his face that I don’t like.

“Yeah,” Pa says.

“They seem like good boys,” Jeb says.

“You the man that killed my uncle?” Benny asks. Pa and Jeb just look at each other.

“Why don’t y’all have a seat?” Jeb says.

On the wall facing the door there are pictures of people that must be Jeb’s children and grandchildren. Every one of them has Jeb’s scrunched, bat-like face and scarecrow frame. I hadn’t thought too hard about what I would find here, but what I see is not what I expected.

“I got a pot of coffee on the stove.” Jeb says. “You boys want any?”

Benny says that he’ll have some.

The place smells almost nice, kind of like cinnamon but with a tinge of cat urine. There is a litter box by the door, but I don’t see a cat anywhere around. On the coffee table is a half-built ship in a bottle, a schooner.

“That’s just a little pet project I’ve been working on,” Jeb says, handing Benny an orange mug of black coffee. Benny always drank his coffee black. I never did see how he could stand it.

“You can just push it on over to the side. It won’t hurt nothing, and please, have a seat. My wife would turn over in her grave if she knew I had company and left them standing.”

We sit.

“You boys are the spitting image of your father.”

I turn to Benny. His eyes are staring down into the black well of his coffee. I know from the look on his face that he’s heard Jeb but doesn’t care. I figured out a long time ago that Benny is Pa’s too, but I never got around to saying anything to Benny about it. His face tells me he knows it, that maybe he’s known it all along.

“What are we doing here?” Benny asks.

“I’m sorry,” Pa says. “Sometimes I just get a little confused is all.”

“Confused?” I say.

“Yeah,” Pa says, cutting his eyes at me. “Confused.”

He looks over at Jeb and there’s something in the way he does it that’s off. I’m a pretty good judge of when Pa is in and out of his mind, and right now he’s in. There’s something else going on with him. I try to decide whether or not it’s worth my time to figure out what it is.

“So what did happen?” Benny asks.

Jeb tells us all about their unit. It was one of the first to integrate and a sort of informal boxing tournament came about between the draftees. It started as a way to settle disputes during basic training, but it continued after they’d seen some action and started missing home. Junior Ross knocked out just about everybody he was pit against due to the strength of his left jab.

“It was almost like fighting a man with two right hands,” Jeb says, rubbing his jaw.

On the mantle above the fireplace there is a large glass placard that reads “Salesman of the Year ’72.” Behind it, there’s a cross, the Catholic kind with Christ nailed to it, only the expression on his face refracted through the glass is one I’ve never seen before. It’s almost like he’s angry, and while Jeb’s speaking it’s all I can see.

“Nobody was supposed to be hurt. Not like that.”

“So who killed him?” Benny asks. He’s holding his coffee with both hands, gazing into the black of it.

“It was an accident, you see—”

“Junior got knocked out,” Pa says. “We got him to the infirmary and for a while it seemed like he was going to be alright. But when the doctor checked in on him the next morning he was dead.”

“Any white soldiers die that way?” I ask.

“No,” Jeb says.

“Seems strange to me,” I say, “that someone could just knock him out like that. Him being such a good boxer and all.”

“Me too,” Benny says.

“The other fellow was a good fighter too,” Jeb says. “I haven’t seen anybody that can hit like that in a good while.”

Pa glances down at his hands. His knuckles are knotted up and scarred. I see in them everything he hadn’t let himself remember before now.

I start to speak, but before I can, I feel something brush up against my leg. On the floor, I see an orange-and-white cat winding its way around my boot, staring up at me, blinking. I nudge it away with my foot and it trots over to Jeb, eyeing me like it doesn’t know what my problem is and it doesn’t want to find out.

“Come here, Josie,” Jeb says, picking the cat up and scratching it between the ears. The cat looks over at me with the smug face of a child spared the rod.

“I don’t think he meant to hurt him,” Jeb says. “Just didn’t know his strength. We were all just boys. We didn’t know what we were doing.”

“Who was he?” Benny asks.

“It’s not my place to say,” Jeb says, turning to Pa.

Benny sets his coffee cup down beside the coaster Jeb laid out for it, stands up, and walks out the door. I haven’t seen him smoke all day, so I imagine that’s what he’s going to go do. That’s probably why he’s been so short and antsy. I don’t allow smoking in my truck on account of James’s asthma.

“Is he gonna be alright?” Jeb asks.

“Yeah,” I say. “He’ll be fine.”

Jeb picks up Benny’s half-empty coffee cup and places it on the coaster.

“Is he mad?” Pa says.

“He’ll be fine,” I say. “Are you okay?”

Pa leans forward, makes like he’s going to cry, and seeing him do it makes me want to reach across the table and give him a good lick to the back of his head like he’d have done to me when I was a boy. But before I can, Jeb takes Pa’s hand in his and squeezes it. The sight of it makes me sick to my stomach. No one had been there to hold my hand when Pa took notion to come for me.

“I’ll be outside,” I say, standing up. “Let me know when you’re ready to go.”

I find Benny smoking a cigarette under a sycamore tree halfway between the house and the road. He’s smoking it nice and slow, so I figure that this is his second. He’d have burned through the first one already.

“Anything I want to know?” Benny asks. He grinds the cigarette into the tree. The red ashes linger on the bark. I wonder for a second if the grass underneath will catch.

“Naw,” I say. “There’s nothing you want to know.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I see something move in the sycamore. I look up but I can’t make out what it is. I turn to Benny. His eyes are on me.

“Momma used to say owls carry death,” Benny says, “and when you hear them you know that it’s somebody’s time somewhere. When I was little I used to sit up by the window and try to figure out who they was hooting about. One night I slipped out of bed, went out the back door, and cut across the yard to try to track it. But it seemed to me the closer I got the less I could hear it. Finally I caught up to it. It was up in a pecan tree, but it wasn’t alone. There was a whole mess of them up there, and when I walked up to that tree all I could see was those big moony eyes of theirs peering down at me. When I saw that I knew Momma was right.”

“What are you trying to say, Benny?”

“I’m saying I heard an owl last night.”

I look to the house. Pa’s still inside.

“I think Pa has a few more good days left in him,” I say.

“He might,” Benny says, lighting another cigarette. “And then again, he might not.”

—

Nobody is in a talking mood, so we ride home in near silence. I drop Benny off at his ma’s house and say I’ll see him later. I tell Pa to lay off the liquor and that I don’t want any more calls from Ma like the one I got that morning. He grunts something in reply.

When I pull up at the house, there is a white-tailed doe standing in the middle of the driveway. She doesn’t seem to want to move; I have to damn near nudge her with the truck to get her to get out of the way. I wait for a minute in case her mate is anywhere around and near as bold as she is. By the time I get into the house, the sun has gone down.

James is at the kitchen table with a bowl of cornflakes and an almost empty box. If I let him, cereal would be the only thing he ate all day every day. From the side, it seems like the stitches are bleeding, but when he turns his head to look at me, I see that they’re just a bit swollen.

“You hear from your momma?”

He shakes his head no.

“She should’ve been back by now,” I say.

He nods his head and keeps chewing. This isn’t new information to him.

“You want me to make you something else to eat?”

He shakes his head no again. It’s a wonder how he got to be such a quiet boy. He certainly didn’t get it from my people.

“I’m sorry about what happened to your face,” I say.

“I know,” he says.

“You know I wasn’t really trying to hurt you?”

“Yes sir.”

“But you know now what to do when you see a knife, don’t you?”

James looks down at his bowl, which by this point is pretty much just milk and cornflake crumbs. “Yes sir,” he says.

I teach my son how to protect himself. He knows when to run and when to fight. He knows to get close when he sees a gun, to back up when someone flashes a knife. Try to pin my boy down. See if he knows how to kick. Try to grab a hold of him. See if he knows how to bite. I don’t go easy on him. I come at him like someone who means to take his life.

“You still hungry?” I ask him.

He shrugs.

“Tell you what. I’m going to make two bologna sandwiches. If you want one then you can have one. If not, I’ll have both. That all right with you?”

“Yes sir.”

“Good. Now go turn on the TV or something. I don’t see how you can stand all this quiet.”

—

The day we killed Ken was the day the woman in yellow spoke to me for the last time. We left Ken’s body in the woods, went to my house, and waited for Sheriff Potts to pick us up. Only Sheriff Potts never came, not then or any of the slow, flutter-hearted, over-the-shoulder-glancing days that followed. I gave Benny a change of clothes and put the bloody ones in the oilcan behind the house to burn with the leaves.

“Don’t let it burn you,” she’d said to me as I put the flame of Pa’s lighter to Benny’s workout shirt and dropped it in along with his pants and shoes. The fire spread out across the bottom of the can. I could feel its heat against my face and the air outside was just cool enough for that heat to feel good. After it burned down some, I took off my own shirt and fed it to the dying flame. When the fire went out, I searched the yard for something else to burn but I couldn’t find anything that needed it.

I try to show my son that life’s not about doing what you want to do. It’s about doing what needs to be done so that you can keep on living. I’ve never been one for the by-and-by, and I can’t claim to know what this life or the next is all about, but I know that if my son were given the choice Ken gave us that day in the woods, I’d want him to choose his life. I’d want him to choose his life again and again.

You can purchase a copy of ASF Issue 72, in which Fayne’s story first appeared in our online store.