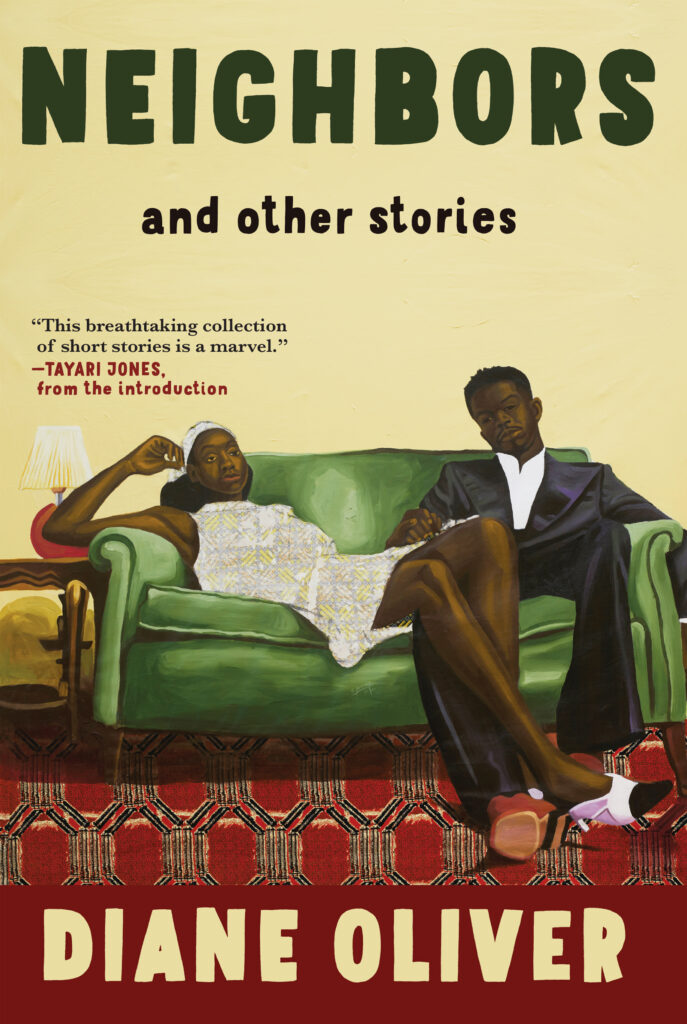

Diane Oliver had published a handful of fiction pieces, one of which won an O. Henry Prize, had edited her college student newspaper, and was about to graduate from the Iowa Writers Workshop–one of the few Black women to have attended the program–when she was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1966 at the age of just twenty-two. Her promising literary future suddenly cut off, she left behind a short, masterful stack of stories that are now being published in a new collection. The stories–like promises themselves–are remarkable in their humanity, their steadiness of voice, their subtlety and control, and the powerful sense one has of a writer willing to take her time, a sense made so bittersweet by the knowledge of how little time she actually had. With great pleasure, we will celebrate that upcoming book, and Oliver herself, with our Constellation Award for a Story Collection at our Stars at Night gala next month. And we are very honored to be publishing what will be the final story in Oliver’s book in our Winter 2023/24 issue. We are happy to offer the story,”Spiders Cry Without Tears,” here as well for everyone to read. Neighbors and Other Stories, by Diane Oliver, will be published by Grove Atlantic on Tuesday, February 13, 2024.

—

“Here comes Meg now.” Sally waved to the woman shaking her umbrella in front of the shop’s glass door. Meg passed the refrigerated case of variously colored gladioli and smiled her greeting to the manager.

“Aren’t you disgusting!” Sally said, circling Meg with a swoop of her hand. “Here everybody else is soaked to the skin. Do you always have to look so good?” Sally playfully made a face at her. “You know, honey, I just don’t feel like the day has started until you come.”

“I’m honored.” Meg smiled and hung up her raincoat.

“Gee, that’s a pretty blouse,” Sally said as they walked toward the worktable. “You’re lucky you can wear almost anything. My neck would be engulfed by all those ruffles. Say, did you have a good time last night?”

Sally turned to scrutinize her friend’s face and seemed relieved when Meg nodded. “He’s a good guy, honey. Warren thinks the world of him, and you should be thinking of settling down. I know. I know.” Sally raised her hand to her eye. “Enough is enough, shut me up quick. Besides, here comes one of your regulars.”

Meg turned on her warmest smile. “Good morning, Mrs. Davis. May I help you?”

The day had begun. Two days down and four more to go, days of blending ribbon with flower color, selecting the right container for the occasion, packing the delicate blossoms into the boxes. She really tried to be helpful when the customer asked, “What do you think?” Talking to people and helping them make up their minds suited her. Even at church socials she always found herself hostessing the women’s teas for foreign missions.

The day had begun. Two days down and four more to go, days of blending ribbon with flower color, selecting the right container for the occasion, packing the delicate blossoms into the boxes. She really tried to be helpful when the customer asked, “What do you think?” Talking to people and helping them make up their minds suited her. Even at church socials she always found herself hostessing the women’s teas for foreign missions.

At first she had taken this job just to have something to do. Talking with strange people, day after day, at least kept her from thinking about Harry. Then Jay was in boarding school the whole winter long. All she did was wake up—the second cup of coffee lifting the heavy sleep that bandaged her mind—and think about Harry. Money was a problem but an unimportant one since Harry kept Jay in school. He seemed to think that sending his son to a military academy would turn Jay into a junior Harold.

And there were small sums of money from home— aunts dying here and there leaving her a few dollars to be banked. Primarily she remembered those days as a series of letters to her son. Letters written when she had nothing else to do. I miss you. I will be glad when Thanksgiving comes, or Christmas, or Easter. And there was really nothing else to tell him. Not even news of a dog because they had no pets. How do you tell an eight-year-old that each year fingernails become more brittle and strange men whistle from buses?

Thank God thinking about Harry had lasted for only a year. To be truthful, a little more than a year. Then she had taken hold of herself and marched down to the Women’s Shop to fill out an application blank. She had always gotten along well with people. Except, she thought wryly, the ones she married. Her father had been horrified when he received news of her job.

“Come home,” he said. “Bring the boy, I don’t like the idea of your living there, with no family.” He had come to visit once—“Nashville’s too big”—and returned home after a week.

The tinkle of the little brass bell hanging over the door heralded the arrival of a customer. He was not the usual kind of customer and that was what disturbed her. There was something about him at first, something she just did not like. Her feelings must have showed as she carefully snipped the dead leaves from a pot of mums. He wanted “something very special”—all right—she would give him so many choices, he’d be nervous before he made up his mind. She opened and closed display cases so rapidly that he barely had a chance to glance at one flower before another was brought to his attention.

All of her actions he took very calmly until finally he spoke. “With a chance to look at one, I might be able to decide.”

The words were spoken without emotion, and before she could control herself, she blushed. For a moment her dislike was intense; and even now she still could not be certain he was colored. As long as those gray eyes watched her, she was uncomfortable. And a lot of them had such straight hair. They were like human chameleons disguised as normal people. Finally he decided on a dozen red roses in an exquisite cut-glass vase.

Each week he appeared on schedule. A bunch of violets, a dish garden, a pot of daisies, a single beribboned dahlia. Always the gift card was signed simply “Walt”—no last name. He didn’t need one. He was a commission— nothing more!

Business was light during the morning. Hour after hour, in between the few shoppers, she watched a transparent stream of rain drip down the awnings that sheltered the shop windows. At ten of twelve Meg tidied the worktable, preparing to leave for lunch, and looked up at him. The navy raincoat was slick with water and glistened as he bent to place his umbrella in a corner near the door. She waited until he walked to her end of the counter.

“Please watch your umbrella,” she said. “Somebody might accidentally walk off with it.”

“Oh you people don’t steal.” For a moment she was not certain whether he was serious.

“Do you?” This time the mockery was evident.

“What’ll it be today?” she asked icily.

“Oh just let me look around a bit—maybe I’ll be inspired.” He gestured toward a bespectacled youth. “Go on and wait on the young man.” He casually examined several potted plants and moved toward her with a gloxinia as she smiled at her customer from the counter.

“I won’t need a card this time.” He glanced at his watch. “It’s your lunchtime.”

“Yes, but I’m not in that big a hurry.”

“You usually eat with a group of talking females. Why don’t you have lunch with me?”

Almost instinctively she turned to see if anyone was listening.

“I can’t go to lunch with you.”

“Somebody might see us?”

“No, I can’t go—you know that.”

He waited until she picked up her purse and then he walked beside her to the door. She could feel the customers staring, but then it could have been her imagination. And he could be a foreigner, some of them were even darker.

“Please have lunch with me, I promise to act just like a kind old friend of your family.” And assuming that she would follow, he raised his umbrella. She felt like a fool. In her haste to avoid him she had left her own umbrella behind the counter.

“Come on,” he said. “I can at least keep you from getting wet.” There was nothing to do but follow him through the glass door. She walked with him to his car, and even as they were driving across town she wondered how she came to be sitting there. He parked behind the grill near the garbage cans, and she had to crawl behind the steering wheel to leave the car. The driveway was pockmarked with mud puddles and inside the walls were blotched with blue paint. The ceiling, patched in places, was whitewashed.

As she walked through the door, the air rushed around them and conversations were silenced quickly until Walt found a table. Then the noise resumed.

“How you doing, Doc?”

“Hello, Doc.” The greetings were muffled and once or twice someone started to speak and hesitated, making her feel uncomfortable. Her eyes scanned the room. “REAL SOUL FOOD,” the sign over the jukebox was silver glitter sprayed on blue cardboard.

“Well, what will you have?” She looked around for a menu.

“It really doesn’t make any difference,” he said.

She felt herself tighten. “What do you mean?”

“What I asked you. There’s no menu. If they have what you want they’ll bring it out. If not, they bring what they think you should have.” He laughed, expecting her to join in. As he spoke, she watched the waitress plod toward them. She wore no hairnet, but each strand of hair looked frozen into place.

“You want the special?” she asked. “Barbecued chicken and lima beans?”

“Two, and iced tea to drink.”

“That’ll cost you extra.”

“Now, Glendora, as long as I been eating here you know I know that.” The mask slipped and her eyes smiled. “Just want to make sure.” Carefully she studied Meg. “Your taste improving.”

He laughed aloud and pinched her arm. “Get moving girl, the lady and I have to go back to work.” She had not noticed until the waitress left that the talking in the room had quieted. Then with each step the waitress made toward the kitchen, the volume was turned up. No one bothered them until they were ready to leave. Then Glendora reappeared with a small paper bag.

“For the dog,” she said. “If you still let him eat bones.” He took the grease-spotted bag and winked.

“Glendora’s like everybody else around here. Sees that simple pup one time and likes him better than me. Hodge Podge and I thank you,” he said. Meg could tell from watching the lines deepen around Glendora’s face that the dialogue was part of a frequently played game. And although she knew he would never say, secretly Walt was pleased.

He might as well have been a widower he told her, although legally he could not call himself that. She could move around the house and occasionally venture outside, but most of the time Marian was confined to her bed. There were no children. At first they had not wanted any, then it was too late, maybe all for the good. Now neither one of them could have cared for children. He did not have time and the disease that crippled Marian solved the problem for them.

He obviously had thought a great deal before telling Meg even that much and then he was silent, talking about his patients or telling her how quickly their new house was being constructed. At night when she was safe in her own duplex, surrounded by normal neighbors, she would look at her son’s picture and wonder, aloud sometimes, what he would think of his mother. Probably nothing, she decided, as long as she never cut his supply of butterscotch cookies.

Involving Jay was silly, and as long as his picture was on her dresser Walt would never come to the house. Not that he would want to come anyway, he still met her for lunch, sometimes for dinner. She never before dated a married man, always trying to be certain Jay grew up without scandal. Having to live with a divorced mother was uncomfortable enough for a child.

She and Walt talked—oh about everything, things neither one of them could discuss with anyone else. Theirs was the kind of relationship where neither one of them was in danger of quoting something said by the other. Talking to him, even knowing that today he might enter the shop, she was unaware of the months passing.

When she had not seen him for weeks, not even in the shop, she would tell herself it was a good thing she had not become involved. Besides, there was always someone who wanted to take her out—one of Sally’s friends or a friend of someone in her bridge club.

“You know, it’s a good thing you’re not married,” Pattie Grier told her the other night. “You’re the only person we know who fits in with everybody.”

“I feel like a television commercial,” Meg answered, and the whole table laughed. Now, thinking about her bridge partner’s words, she was vaguely disturbed.

“You’re still young,” Sally was always saying. “You really should settle down. Warren and I will send Jim to pick you up at eight.” She heard Sally’s speech so often she was amused at her friend’s seriousness.

On Sunday evenings she could count on being invited to the movies and to Sally’s house for supper. The new discovery would always call and suggest another date, and she would go because she enjoyed being with other people. Through the years she lived in Nashville there had been a steady succession of men—there was somebody named Stan something and for a while she dated Warren’s cousin, Joe. Sally’s latest discovery was Mike, who worked out of town during the week, coming home for the weekend. Since she did like Mike, Meg had a good excuse not to be free when Walt called. She knew that sooner or later she was bound to lose the distance between them, and knowing this she became determined to put Walt out of her mind. Just when she had succeeded concerning herself with Mike, he would come in at noon the next day to buy Marian’s flowers and Meg’s lunch.

Her life at home and at the shop were completely separated. Jay came home only on vacations and now he went around with his college crowd. Once, teasingly, he told her about one of the neighbors declaring his mother hid away a new boyfriend. For a horrible moment she dared wonder how her neighbors discovered Walt. Then she saw he was smiling and remembered bumping into Wanda Hardy when Warren’s Mike escorted her home from a party.

At the Blossom Shop new orders came in weekly and so did Walt unless he called to meet her for dinner. In spite of herself she saved every hope for the weekend when he could put away the prescriptions and leave a nurse to wait on his wife. Sometimes even the weekends did not belong to her, but Mike was always there with the endless supply of tickets. And so she convinced herself that she did not miss Walt when Marian rallied and actually seemed to be improving. Then there was a relapse. At these times she never questioned Walt but was thankful she had him for as often as she did.

This funny relationship—sometimes weeks would pass before she even heard from him. Sometimes too, there would be a note about his wife in the news. Of course not on the society page, but she was active enough to be mentioned in the local news columns. From her bed, Marian still managed to speak up for charity groups, and to serve on community boards, even to have neighborhood meetings at her home.

Whether she would sleep with Walt had not been a question for Meg. After a while he just assumed that she would. That first time she had awakened before light began slipping through the venetian blinds, feeling that some bit of uneasiness should have come. But in the halflight there was nothing to disturb her. When the sun had been up for hours and she had to face herself—comb her hair and brush her teeth—perhaps she would be ashamed. Maybe for her grandmother’s sake even disgraced. She was probably the first Kelham to spend the night at a colored motel. And the thought made her smile. Then there was nothing, no emotion, only sleep returning. She had become accustomed to having him beside her.

Gradually as the years passed she gave up the idea of remarrying, as if she had ever seriously considered another marriage. Oh, she could have brought Mike around to proposing—once, playfully, half seriously he had asked if she would like an engagement ring. But the first go-round on those godforsaken army posts had been enough, and now Harry was a part of her life that no longer existed. On common-sense, practical grounds her life with Walt was nonexistent. Mike was a good thing to have around. He was like herself, permanently unattached.

Whether she wanted to or not she found herself comparing Walt with Harry. She often thought it was too bad she had not waited around for someone like Mike in the first place. He would have been the kind of boy her parents liked—never questioning anything, just accepting and expecting a pleasant, minor-problemed life. He fitted in so neatly with their way of living. They told her at home she was too headstrong, especially to be a girl. “Nutmeg,” as she was called then, often thought that the discontent felt by generations of Kelham women had built up and culminated in her.

She did not want to spend the rest of her life being a Kelham lady. All the girls in her family marched in the annual Daughters of the Confederacy Parade, smiling at the groups of Negro children who waved them to the cemetery. There was never any question about a new white dress until she was eighteen. Then her mother nearly had heart failure before Meg agreed to take part in the Memorial festivities. Her family did not understand where she got these crazy ideas. And, looking back at a childhood filled with piano lessons and Twinkle, Tweener, and Teener parties in that age order, neither did she.

Her father packed her off to the Episcopalian junior college to make sure she learned some sense. The college was located near an army base and although there was no written rule, everybody understood that Saint Mary’s girls did not associate with soldiers. Harry was a soldier then, neat—not good-looking in his uniform.

He seemed to know about everything. He too did not want to live in his hometown with people constantly gluing their eyes down his throat, expecting things of him he was never certain he wanted. Late one Thursday when everybody was leaving campus to begin an early weekend, her dorm roommate showered her with rice behind their locked door. She signed out for home and in November of her freshman year, she and Harry were married.

The excitement wore off too soon, but since she was an only child, her parents could not disown their baby. Her father even offered to help Harry find a job in the real estate business, but Harry was a soldier by profession. Her parents sent them money, enough to buy things for the baby and clothes for herself. She was never exceedingly happy or unhappy, although during the first year she supposed she thought in terms of contentment.

Harry’s desertion when Jay was eight was not really a surprise. She went home, enrolled Jay in school, and helped her father in the office until the school year ended. Then, looking around her house, at the relatives lined up on the mantel and the living ones lined up in towns throughout the state, she was determined not ever to be stuck in South Carolina. So, packing all of their belongings—nothing was much of a keepsake—she and the child came to Nashville.

“One daughter and only one grandchild.” Her mother felt cheated having reared only one child. Now Meg had betrayed her by limiting her number of grandchildren. Meg went home only occasionally, usually to attend funerals. First her mother and a favorite uncle brought her back to Sumpter in the same year. Then another uncle, and a cousin who cheerfully steeped her tea with whiskey, and finally her own father. Although the aunts urged her to come home again, she rented the house and returned to Nashville. And to Walt.

Somehow, even consciously being careful, the years made her careless. Thinking in terms of “Walt and I” was natural. One afternoon, just before closing, Sally asked if he were Portuguese.

“I mean how on earth did a Portuguese get this far south. Listen Meg, I don’t mean to get mixed up in your business but everybody is talking. They say he looks like he’s trying, well you know, to pass.”

She had become quiet waiting for Meg to deny the accusation. “I told everybody they were just being silly, that he was only your customer. And even if he did look White you wouldn’t be mixed up with colored people. Besides, I told them you were going with one of Warren’s friends.”

The pencil shook as Meg tried to set it down without Sally guessing the frequency of her trembling. “I usually take care of myself,” she answered.

Sally looked hurt. “All right, I didn’t mean anything. I should’ve kept quiet, but you know Mr. Morgan wouldn’t like what you’re doing behind his back.” She quickly turned around. “Oh honey, I wouldn’t say nothing to him about your private life for anything in the world, but some of these people just might. I didn’t want to say anything,” her voice was pleading, “but the other girls wanted me to tell you they knew.”

“Well, you tell them we both know.” She was amazed at herself even daring to answer Sally. She did not understand from where the bravery came. She liked the other girls and thought they were friends of hers. They seemed genuinely happy for her when she was chosen assistant manager. But Sally never would have spoken unless she was really worried. And with her honest do-good nature, Sally was better off uninvolved in controversy. So, with the same quiet approach with which she once sought Sally’s friendship, she now widened the distance between them.

Meg was not aware of the slights at first. Everything seemed to happen at once; only later did she realize that the incidents had been building. At lunch, sitting at the Woolworth’s counter she and the girls talked about the usual things. At Thanksgiving they did not ask for her contribution to the shop’s needy family. She just happened to see one of the girls collecting money and gave her the dollar bill.

The Thanksgiving basket she did not even think about. What really bothered her was being ignored when the group planned a party for Christmas weekend. She would not have known about the party if Sally had not mentioned Warren’s buying a new suit for the occasion.

“But honey, I thought you knew all the details. The committee’s been planning for weeks. Emily called everybody personally to make certain they got the time down pat.” Then she stopped. “That ass, she purposely didn’t call you. We wondered why Mike didn’t act as if you had invited him.” Sally was quiet again.

“Never mind,” Meg turned away, “I couldn’t go anyway.”

For some reason they did not try to take away her job. She was not certain whether the other girls lacked nerve to complain to Mr. Morgan. But he did not act as if anything strange was occurring. After thinking of all of her coworkers, she rather thought the management did not know.

A long time passed since Sally had invited her out. Meg sat at the kitchen table, manicuring her nails. Sally was still friendly at the shop but they no longer spoke of personal matters. She could never keep anything from Warren, and he definitely would not approve of Walt. One of Warren’s major quests in life was to find restaurants that Negroes had not yet integrated. Then when his stronghold was invaded, he went in search of another one. She and Sally used to laugh at Warren’s great stalk. Now that she was contaminated, Warren probably had Sally strike her name from the list of people to be invited places.

Then, as if Sally had heard, the telephone rang with an invitation to Sunday supper.

“Jay is home for the holidays and leaving Sunday.”

“Oh honey, pack him off in the afternoon.”

She explained that she wanted to spend the last day with him because he was visiting his roommate for spring break and would not return home until June. Besides, she had told Mike she could not go to a movie that evening because of Jay. “What about a rain check?”

Her voice was much brighter than it should have been. Sally was silent for a second.

“Sure thing, honey.”

Immediately after Jay’s plane slipped off the ground, she rushed home to wait for Walt’s call. The telephone rang once when Jay phoned to assure her of his safe arrival. She still did not regret refusing Sally’s invitation—even after several months when she realized there was never another one.

Mike kept calling though. She could not decide whether he never saw Sally or Warren, or if he was just curious about her. He never asked about her life during the week, but then she did not question him closely at all. The last time she was out with him he asked why she was not wearing lipstick. With a shock Meg realized she was absorbing so much of Walt. He disliked lipstick, teasing her so much about wearing the protective coloration—that finally she acquiesced, returning to bare lips. In trying to please him she was turning into a little girl, incapable of rebelling.

She talked to Walt on Friday. He was in a hurry, speaking quickly, and in her mind’s eye she could see him doing something else, probably completing a form while he talked to her. She would not see him until later, next week, because Marian again was ill.

Tuesday during her lunch hour she and Sally were sitting in Woolworth’s coffee shop reading the newspaper before the waitress brought their soup. Just by accident her eyes skimmed the obituary column. She must have let out a soft cry because Sally put down the comics.

“What is it honey?”

“Nothing,” Meg answered, burrowing behind the paper, trying to keep her hands from trembling while she read. “. . . SURVIVORS include her husband, Dr. Walter Carter of the home; a sister, Mrs. Bernadine Cleveland of New Orleans . . .” Five minutes must have passed before she realized the waitress had come and left. The peculiar thing was that if anyone had asked, she could not have said how she felt.

There was nothing to be happy about; they would always have to be careful. The way her friends acted at the shop only meant they would have to be more cautious in the future. Oh, she supposed for a minute the possibility of marriage was a conscious thought. But she was not completely crazy or so much in love that she would subject herself to the solitude his marriage would impose. Putting the paper under the counter, she carefully lifted the spoon and watched the soup shake in her hand.

Every time the phone rang she jumped, and when he did call, he assumed that she knew. Just like that, as if she pored over the obituary columns waiting for news of his wife’s death. She never would ask why he had delayed calling. That would be admitting something and at the time she admitted “nothing to no one,” not even to herself. Walt saw her once in June and that was to tell her he had decided to take a vacation.

“A long one.” His eyes looked tired. “Marian’s sister is going to get the house in order and I could do with an airing out.”

They were sitting in the same grill, at the table under the largest patch on the ceiling. The waitress had taken the order on her grimy pad and they sat waiting for Glendora to bring their plates. Now when she followed Walt through the door, the men tipped their hats and the waitress acted as if she was not an eyesore, or a museum piece from another world.

“I’ve got to straighten out things and now’s as good a time as any.”

She was sitting by the window and as he spoke, her eyes circled first the room, then the scene planted outside the window. The boards of the house next door were gray where the paint had peeled, exposing the colorless wood. Next door was a beauty parlor and they were close enough to hear the whirring of the electric fan in the window.

“Why don’t you come to Atlantic City for the weekend? You could fly down on Friday and be back by Sunday night.”

For a moment she was covered with excitement, actually going somewhere, a place where neither of them had to care what anybody thought. Even that was impossible. A lot of Jay’s classmates worked in the resort area during the summer. He had just graduated from the university in May; she would not take the risk of encountering his friends, and shaming him. He was still too young not to care what people thought.

“Well?” He leaned over toward her. “What do you say? No? Don’t you want to come?”

“Of course, but I can’t. I just cannot go.” She hoped he was not angry. He did not mention the trip again and when he stopped the car a few yards from where her car was parked, she jumped out before he could say goodbye. Both of them would be much better off if the night were a permanent goodbye.

He did not write from Atlantic City, not even a postcard. They never exchanged letters, yet every afternoon, hoping perhaps—she was never certain—she quickly shuffled the mail. There was nothing, just the bills and letters from Jay, who had a government job in Baltimore.

Saturday she came home thankful for the promise of a day of rest. She had told Mike she could not possibly have dinner with him. He had sounded hurt but she knew him well enough to know that he would call again. He was funny about her, telling her that no other woman he dated would dare be so unpredictable. “I’m just partial to pretty women,” he said, kissing her good night. Not that she was hard to decipher—one minute particle of Southern womanhood gone to hell. She would like to see his face if he knew about Walt. Warren probably had told him something, but Mike thought she was incapable of lying. He would call again, next weekend, curly hair slicked down, asking what she wanted to do that evening. She would go out with him, having nothing constructive to do, except not to think about Walt, to keep him out of her mind.

Meg recognized the car when she pulled into the driveway. Then she was slamming the door and running around the back of the house. He had never come here before and he would not have come now unless he wanted to say something final. She slowed her steps until she again was in control and there were his long legs straddled on the porch, his coat unbuttoned, his clothes looking positively thrown on him. A delivery man once, the girl who had stayed with Jay when he had chicken pox and she could not take leave from work—these were the only colored people who had set foot in her house. And now him. Immediately she was ashamed; even after these six years, she thought of him in terms of color.

She had to think a long time before she agreed to marry him. Then she realized there was nothing to think about. She had succumbed so long ago, the time did not matter. Jay came home one weekend for part of a weeklong vacation. She tried to act like a normal mother, asking if he was getting enough rest and eating his green vegetables. But since he had finished school, she really no longer controlled his actions. She waited until Sunday for him to get settled, then announced that she had thought of marriage.

“To who?” he asked, his head stuck in the refrigerator.

“Dr. Carter. Walter Davidson Carter to be exact.”

“A rich and wealthy surgeon. Hah! Mama, you’re coming up in the world.”

He chuckled and came over to kiss her on the cheek. “I’m glad Mama. Is he from around here?”

She watched him drink the Coke, counted to five, and said that the doctor was a Negro. He put down the bottle and stared.

“Mama, if you want to play games, come up with something else.”

She did not move and seeing her stand so still, he knew. “Mama, why?”

“He’s a good person, Jay.” Good indeed, she reminded herself of a soap opera heroine. “We have been together so long . . .” She stopped abruptly. No, not even that sounded right to say aloud. The words belonged to her own ears.

“Mama, you know I have nothing against them. They went to school with us but they didn’t bother anybody. My God, Mama you’re going to be one of them.” As if that thought was too horrible to utter aloud, Jay turned and left the kitchen.

Jay did not come home that night. Neither did he come home the next day. On Tuesday afternoon when she had almost given up talking with him again, he came to pick up his luggage.

“I’m sorry for you,” he said. “I only hope he’s too old to have children.” And then her ears stopped listening. In his eyes there was pity for her and unless she did not know him well after twenty-two years, pity for himself.

In February she resigned; in February she was married again—a simple transition. There was no need to move anything, none of her furniture would fit into his house. And so she had under the bed in the guest room, in a locked suitcase, Jay’s baby pictures, a few letters she had saved to remember something good about Harry, and a pair of shoes. They were the same shoes she had worn every other day for four months when she first met Walt. She supposed she should have pitched them out, or had the heels slimmed, but she preferred having them shut away. Knowing that they were there was important, knowing something in this house belonged to her.

For a long while she did not hear from Jay. Then a letter came, full of formal phrases. She could not expect to see him at home. Anytime she wanted to come upstate to visit she was welcome, alone. The letters came regularly, twice a month. On those days when the mailman brought the letters or even when the wrinkled blue envelope was overdue she found herself in the guest room, pulling the suitcase from under the bed.

She avoided looking at the box beside her simple piece of luggage. The same elegant lettering engraved on the cardboard box was etched on the label of her stole.

“Happy birthday, baby. You’ll look good in this.”

The box was conspicuous on the sofa when she came home from driving. She did not even have time to comb her hair before he, warm and antiseptic, was bending over her and the package. Funny she had never noticed he had such a distinct smell, like his office. Her fingers untied the knot and the cord, dividing into quarters the words “Dillon Furriers,” fell to the floor. She picked up the stole and, rubbing the fur against the nap, did not know what to say.

“I’m glad you like it.” He did not ask but assumed that she was pleased. Not until after supper when they were sitting in front of the television watching some medical drama that absorbed him did she remember.

He had talked once of having picked out a stole for his wife. The furrier held it in reserve as a spring surprise for Marian. With warm weather she would go outdoors again. That spring had passed. Now another autumn was almost ending and Marian’s stole had come home from the furriers. She looked at Hodge Podge stretched across Walt’s knees, making a rug of blond ringlets on his pants leg. The tears went down her throat and to the cushion inside. He could have picked out another kind of fur—at least a different style in which to wrap his wife.

During the Thanksgiving holidays at the one dance Walt decided to attend, Helen and Pete Harbison greeted them in front of the hatcheck counter. Helen had been one of Marian’s childhood friends.

“Marvelous,” Helen said, covering her with a glance while the men checked their wraps. “Marian would have loved it.”

“Loved what?” Peter asked. “Who would have loved what?”

“Let’s go inside,” Helen answered, “you two come along.”

Since Thanksgiving the stole had remained underneath the bed.

For the length of time she stayed, Meg might as well have not gone to college. All of her neighbors were graduates. She knew nothing about sororities except to comment on the college girls who occasionally came to the shop, but after a while there was nothing else to say about them. And the stiff little brunches and bridge meetings in her honor to show Walt they accepted his wife. She always felt the party began after she left.

Some of the women were friendly. They always told her how nice she looked. They asked her to join the medical auxiliary, and included her in plans for neighborhood barbecues; but at the end of these get-togethers, she received no individual invitations. Always she was invited only with the group and she had to wait for them to make the first gesture. Of course she called them for lunch and to play bridge, but again they came and left in a group. After a few months she stopped entertaining altogether.

So seldom did the doorbell ring that she found herself nervous when answering the door. Yesterday she was almost speechless when she saw Debbie Gabriel standing on the other side of the screen. Debbie, who had been Marian’s college roommate, did not seem to notice the strain. Hodge Podge yelped so furiously with happiness at seeing her that both of them were embarrassed.

“He remembers,” she murmured, half apologetically.

“I wish he’d be half as affectionate toward me.” Meg meant the half-serious words as a joke.

“No, he’s Marian’s dog.” Debbie picked up Hodge Podge before she cut short her words.

Even when Walt was home the dog ignored her— maybe she should say especially when Walt was home. Hodge Podge had been a gift to Marian from Walt, but Marian was not able to feed the puppy or take him for walks and in a few weeks the dog belonged to Walt.

Debbie and she talked about the Christmas holidays and a new fruit cake recipe she planned to try. Meg had learned to cook as a child and ordinarily she would have enjoyed exchanging recipes. But both of them were trying to leave Marian’s name out of the conversation and after several embarrassing silences, Debbie left, explaining that she had to pick up her son from band practice. Debbie was the only woman who had come to visit without her husband.

Walt’s house was like a mural on a funeral home calendar. She could always mark the days, blot out each number, and then rip the month away, making visible the next allotment of time. No matter how many days passed she still woke up in the morning, washed the breakfast dishes, and if it was the maid’s day to clean, made herself busy in her own room or car. In either space the windows were always open and she did not know whether she was letting something in or trying to keep inside something she could not describe.

After Debbie left, she sat in the living room trying to decide when she finally had adjusted to the routine of this house. She had adjusted quietly, exactly as she had to every other phase of her life. There was a sun deck over her head, and French provincial in the bedroom. Lots of women would envy her in this position, and as she walked through the house, straightening the books, finding odd jobs ignored by the maid, she admitted to herself that she was past caring.

Tomorrow morning at eight o’clock she would get up in time to make coffee for Walt and herself. Since he had to watch his weight, breakfast was always the same—a boiled egg and orange juice. At least his simple breakfast gave her a chance to dress, to take her time in smoothing liquid make-up over each tiny imperfection of her complexion.

One of those weekday mornings when she had come out of a heavy sleep and sat down at the kitchen table, her face merely licked with a damp washcloth, she saw what had not occurred to her. She looked down at her hands, even nail polish did not camouflage the wrinkles and she was shocked not having before seen her age. A natural process, of course, but to discover that now she was completely dependent on Walt. She no longer had a choice of going or staying. Since she had become a part of this world she could never completely return to what she had left. Who else would want her? She tried to think, to come up with an honest answer, and at the end of her thoughts there was only an abrupt “no one.”

Walt could have someone else. Someone to him as she had been during Marian’s illness. Only she was not incurably ill. He owned her exactly as he did the house, the cars, and those poor people who thought their hearts would collapse if her husband retreated from medicine.

Just then Walt strode through the door, bringing the morning paper. Hodge Podge, scuttling along behind him, stopped to sniff at her before hopping into a chair. Instead of moving the dog, Walt sat at the other end of the table. Although he smiled as he cheerfully said good morning, she saw herself as he saw her, aging, even under make-up. Since then she had busied herself not thinking, filling her mind with whatever she saw, or heard, or read. And read and read.

Tomorrow morning she would awaken at seven-thirty and by eight she would be dressed—not exactly as she was today, because tomorrow was not a shopping day. One of the ground rules of her routine was that no two consecutive days would be devoted to shopping. She had been downtown all morning, making a few purchases, but spending a great deal of time looking, waiting until lunchtime.

Out of habit she found herself standing in front of Woolworth’s revolving door. She entered the dime store and walked past the hair-care counter and notions to the snack bar. Lord, there had been so many lunch counters in her life. She probably could turn into a Woolworth’s counter if she tried hard enough. Putting her packages under the counter, she looked at herself in the mirror. Her brown eyes reflected absolutely nothing.

The waitress was slow, but no matter, there was no place to go but home. Soup here or soup at home made no difference. In her kitchen the people she talked to usually were characters from the Literary Guild book selection. Here at least the people moved, swiveling themselves on stacked-pancake stools to face the countertop.

“You’d think those people would be satisfied by now.”

The words slurring together came from her right, the woman’s face appeared from behind the newspaper. “All those demonstrations, really they’ve run things into the ground.”

Meg looked past the woman to the article on the front page and read the dateline from some small Georgia town, one she had not before heard of.

“I don’t know,” she said, trying hard to be polite.

“Well, it seems to me,” and the woman tugged at the scarf covering her hair, “seems they’d be satisfied and try to use what they got now.”

“I don’t know,” she said again and turned to watch the waitress bring her soup.

She did not know—and by now she should know what to think. Even a year before her opinion would have been no problem; she did not have to think at all. Now she found herself trying to hurry the day, waiting for the next morning when all of the hours until tomorrow would have passed. Then there would be one less newspaper headline to remember, to associate with her own life.

Tomorrow she would get up and unpack all of the bags and boxes that had been purchased last week and today. Then, up to the attic to bring down the luggage stored away since their last vacation.

This year Walt was taking off for a month to travel in New England. She would need unlimited changes of clothes, and packing would take a great deal of time. If she worked slowly she could stretch the job into two mornings. Lord, she could remember the days when there was not enough time to finish anything. After lunch, by the time she could drive home from downtown, the kennel manager would be expecting Hodge Podge. The dog was growing old and Walt did not feel travel would be healthy for him.

Taking the spaniel to the kennel would be her afternoon excursion. Imagine that. Nothing to do but take a simple dog to a kennel or spend the afternoon watching soup grow colder.

Meg turned to look again at the headline, but the woman with the newspaper was gone. Everybody at her end of the counter had gone. In a few minutes she would be sitting alone. Suddenly Meg could not wait for the waitress to return, and reaching into her purse, she pushed a dollar bill on the counter. Strangely conscious of no longer carefully counting her change, she picked up her packages and slid off the stool.

She did not run through the store; her heart was beating so quickly she only felt as if she ran. She stumbled past the door marked PUSH and walked blindly to a display window. Staring down at the case filled with beach toys she tried to keep her eyelashes from becoming wet. “Dear God. Dear God.” Over and over again. She stood by the thick glass not knowing the words could be so deep within her. Finally, the sound of her own voice comforted her, the words pushing her home and toward Hodge Podge’s kennel.

Diane Oliver was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, and after graduating from high school, she attended Women’s College (which later became the University of North Carolina at Greensboro) and was the Managing Editor of The Carolinian, the student newspaper. She published four short stories in her lifetime and three more posthumously: “Key to the City” and “Neighbors” published in The Sewanee Review in 1966; “Health Service,” “Traffic Jam,” and “Mint Juleps Not Served Here” published in Negro Digest in 1965, 1966, and 1967 respectively; “The Closet on the Top Floor” published in Southern Writing in the Sixties in 1966; and “’No Brown Sugar in Anybody’s Milk’” published in The Paris Review in 2023. “Neighbors” was a recipient of an O. Henry Award in 1967. Diane began graduate work at the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop and was awarded the MFA degree posthumously days after her death, at the age of 22, in a motorcycle accident in 1966.

“Spiders Cry Without Tears” is excerpted from NEIGHBORS AND OTHER STORIES © 2024 by Diane Oliver. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.