“Whatever happened, it happened in extraordinary times, in a season of dreams, and in Natchez it was the bitterest winter of them all.”

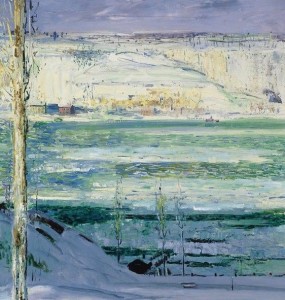

The opening of “First Love” is the best prose Eudora Welty ever wrote. In its welcome sweep, we perceive the “red percussion” of Indian fires in the distance, the mute wheel of gulls, travelers picking through the “glassy tunnels of the Trace” in the “strange drugged fall of snow,” and the “somnambulist” river lifting from its bed in subconscious craving for travel, for new geography. The world is frozen by an epic, battering cold, as if the Arctic has dipped its white paw into Mississippi. What’s more, this is a world of silence, which prepares us to enter the vantage point of Joel Mayes, the deaf-mute orphan to whom Eudora Welty yokes her story.

The opening of “First Love” is the best prose Eudora Welty ever wrote. In its welcome sweep, we perceive the “red percussion” of Indian fires in the distance, the mute wheel of gulls, travelers picking through the “glassy tunnels of the Trace” in the “strange drugged fall of snow,” and the “somnambulist” river lifting from its bed in subconscious craving for travel, for new geography. The world is frozen by an epic, battering cold, as if the Arctic has dipped its white paw into Mississippi. What’s more, this is a world of silence, which prepares us to enter the vantage point of Joel Mayes, the deaf-mute orphan to whom Eudora Welty yokes her story.

He has lost his parents—who knows exactly when or how. Joel’s memories are threadbare. Once, a crew of white settlers was guided silently through the canebrakes so as not to be slaughtered by the indigenous people. Even a mute child can yelp in fear, and with a cutting look from the pathfinder and a wave of the hatchet, Joel buried his mouth in the leaves. When the Indians passed by Joel’s hiding place, “they passed in the length of the old woman’s yawn.” His savior deposited him at a tavern where he could black boots for his keep.

“Flatboats and rafts continued to float downstream, but with unsignaling passengers submissive and huddled, mere bundles of sticks; bets were laid on shore as to whether they were dead or alive, but it was impossible to prove it either way.”

Joel’s world is a wilderness outpost, the very tail of the Natchez Trace. A place redolent with American myth: its Chickasaw and Choctaw, its Great Awakening and commercial travel, its brigands and cypress-kneed swamps and shifting lowland rivers that rouse themselves like bedded beasts. The Trace has de Soto’s peregrinations behind it and Meriwether Lewis’s suicide ahead. And Joel Mayes, an American nothing, like so many of us.

Eudora Welty immerses us in river water, in time, in Joel. “He did not despise boots at all—he had learned boots; under his hand they stood up and took a good shape. This was not a slave’s work, or a child’s either. It had dignity: it was dangerous to walk about among sleeping men. More than once he had been seized and the life half shaken out of him by a man waking up in a sweat of suspicion or nightmare, but he dealt nimbly as an animal with the violence and quick frenzy of dreamers. It might seem to him that the whole world was sleeping in the lightest of trances, which the least movement would surely wake; but he only walked softly, stepping around and over, and got back to this room. Once a rattlesnake had shoved its head from a boot as he stretched out his hand; but that was not likely to happen again in a thousand years.”

The passage contains all the mystery and promise that fiction can possibly hope for: the pleasures and agonies of human experience, the deft use of time, a genuine world, a roiling history that is both personal and universal. “First Love” has so much to recommend it. Aaron Burr and Harman Blennerhassett arrive in town, soon to take part in their fabulous trial. One feels, with excitement, the gears of plot catch. They connive in Joel’s tavern crawlspace, those splendid traitors, as the boy watches from the margins of history. With a delicious touch of clairvoyance, Joel pieces together Burr’s “genius” from the illumined looks the great man inspires on others’ faces. The space is transfigured. After all, it is a season of dreams.

The passage contains all the mystery and promise that fiction can possibly hope for: the pleasures and agonies of human experience, the deft use of time, a genuine world, a roiling history that is both personal and universal. “First Love” has so much to recommend it. Aaron Burr and Harman Blennerhassett arrive in town, soon to take part in their fabulous trial. One feels, with excitement, the gears of plot catch. They connive in Joel’s tavern crawlspace, those splendid traitors, as the boy watches from the margins of history. With a delicious touch of clairvoyance, Joel pieces together Burr’s “genius” from the illumined looks the great man inspires on others’ faces. The space is transfigured. After all, it is a season of dreams.

And yet, and yet, as a short story, that demanding form, “First Love” doesn’t quite come off.

* * *

If Eudora Welty’s first collection (A Curtain of Green) is most praised, her second, The Wide Net and Other Stories, is the work of a seasoned, risk-taking author who is confident in her abilities, if conscious she spent up a good deal of fuel on her debut. She is wise enough to return to her desk with trepidation. Small-town Mississippi, her proximate scene, that “carnival at Carthage” with its Baptist hairdressers and its pans of cut zinnias, is not enough. She reaches beyond herself, to the country of myth and dream, grabbing hold of Natchez to accomplish that rare thing: she vaults beyond her own estimable gifts. She out-writes herself.

Hence the startling pages of “First Love.”

In the collection, “The Wide Net” and “First Love” are most compelling. I have sung the praises of the former elsewhere and will not indulge myself here, except to say that it is as near to perfection as the short story, in its maximal variety, can be. Its strengths will be obvious to any thoughtful reader, the way it rides the swell of its conversations, giving the story a thrust that “First Love,” its neighbor in the collection, necessarily lacks.

In the collection, “The Wide Net” and “First Love” are most compelling. I have sung the praises of the former elsewhere and will not indulge myself here, except to say that it is as near to perfection as the short story, in its maximal variety, can be. Its strengths will be obvious to any thoughtful reader, the way it rides the swell of its conversations, giving the story a thrust that “First Love,” its neighbor in the collection, necessarily lacks.

For in “First Love,” Ms. Welty makes the brave choice to tether the story to a deaf-mute child; with care and precision, she undercuts her greatest natural gifts as a writer, voice and dialogue. It’s the stylistic equivalent of ripping out your own tongue. Voice is what made Eudora Welty a name, and though I must admit I hate the chirpy, anthologized “Why I Live at the P.O.,” the story spawned a thousand bad novels narrated by precocious genius-children. It warned me off her for years until I wised up, encountering the outstanding “Lily Daw and the Three Ladies” and “The Hitch-Hikers” in all their Chekhovian horror.

“The Wide Net” is fleet of foot, but “First Love,” after its masterful opening, begins to bog in Joel’s consciousness, in his one-sided obsession. Because the author does not (cannot?) allow him to communicate with the other actors, we must spend our time in Joel’s mind, observing as he observes. The narrative slows, a frozen river.

Or perhaps my complaint is that Burr pays little mind to Joel Mayes, the one who loves him most.

Most of us stand outside history, right? We are the plowmen and so what if Icarus falls. I am a West Virginian and like all my countrymen and women I’m skeptical of kings and newspapers, governance and fame; I have a peasant’s view of history, marked only by the wheel of the seasons. Reality teaches us that the celebrated Burr would never notice Joel. But “First Love” is not real. It is fiction, in all its artifice and glory. I crave Joel’s agency. I want the tale to pivot decisively on his decisions. Yet he remains the consummate outsider. His role is static. Yes, Burr wipes his face with Joel’s boot rag, in order to escape incognito, wearing the turkey-feather cap of a Choctaw, but one suspects that any handy rag would do. Yes, Joel’s realizations at story’s end ring true, but I need him to be more of a character, not merely a lens through which to examine a great man. The cathedral-builders are more interesting than the kings who scratch an itch for cathedrals.

Is this why the story doesn’t come off for me? I’m still not sure. I love the risks Eudora Welty takes here. I’ve read this book in two, and “First Love” is the tale to which I most return. There’s pleasure in every line. What a riveting failure, one that towers over the ‘successes’ of conservative artists. I admire the fact that she placed snares in her own pathway, even if she could not surmount them.

Or maybe she did; I might change my mind next week. As I said, I’m still in love.

Matthew Neill Null is a winner of the O. Henry Award and a recent fellow of the Michener-Copernicus Society of America. His short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Ploughshares, Baltimore Review, and West Branch, among other journals. He administers the writing fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts.