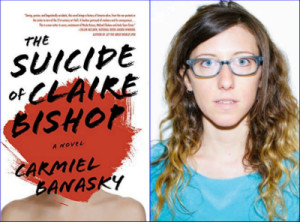

Editorial Outtakes is a feature in which we publish excerpts from novels and story collections that you won’t find in the finished books because, prior to publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features Carmiel Banasky, whose prologue to her debut novel The Suicide of Claire Bishop was cut from the manuscript at the proverbial last minute. Here’s the disappeared prologue, followed by Banasky’s commentary on the process of writing (and then cutting) this part of the novel.

Editorial Outtakes is a feature in which we publish excerpts from novels and story collections that you won’t find in the finished books because, prior to publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features Carmiel Banasky, whose prologue to her debut novel The Suicide of Claire Bishop was cut from the manuscript at the proverbial last minute. Here’s the disappeared prologue, followed by Banasky’s commentary on the process of writing (and then cutting) this part of the novel.

—

The Suicide of Claire Bishop

Prologue

2004

I am a lie. But I am not a liar.

What I am is a good enough man, which is why I’m telling you, Dear Listeners, starting right now, every truth I have ever known. Here is your first truth: My name is West Butler and I am the masked thief in the gallery, stealing the painting, always.

My face sweats behind my ski mask (pink, not black—don’t ask). I take the canvas in both hands and lift it from the wall.

I have dropped pieces of myself all over time. I’m afraid someone will figure out the mystery of me before I do, and they’ll glue me back together wrong. I’m punched through with self-loss.

Time falls around me. The gallery walls crumble brick by brick. Through the bouquets of mortar and dust, I see the ancient meadows of the city. They hover above the sidewalks, the traffic cones, running down to the estuary and the sea, marble-blue. I see the layered shinbones of our ancestors, and feel the soil between my toes, the wild marshes of the Bronx. Beyond that, hanging over it like the pewter shadow of a bird, is the liquid future, shimmering and proud. The high clouds. The satellites. All shot through with light.

Briefly, I enter the painting: the cobblestone street, the Brooklyn Bridge, the body of a woman falling. Every brushstroke an apology.

I crawl into the painting. I am the little man in the corner of the image, nearly invisible, walking down the painted street. I tap my foot on a cobblestone, smudge it.

Do you remember how, when she left, my heart crawled across the floor like a crab? At least I could find it again if I needed it, follow those tracks behind the bookshelf.

She took all her paintings with her but forgot her paints. I used one of her palettes and threw a few brushstrokes on an unstretched canvas tacked to the wall, not enough to see that I lacked her skill, then left the apartment. I don’t know where I went—for hours I was somewhere, because I could not have been nowhere—and when I returned home I saw the canvas and knew she’d been there while I was away, painting alone in the dark.

I have formed and reformed our story because that is how I will find her. Back then, I could think into her bones and know she felt my presence, my breath keeping time, a shoulder blade slipping under a palm. I time-traveled by conjuring her body.

But now I no longer feel her. Maybe she’s in India. Or Israel or Home Depot or the moon. If I’m right, clap twice. I try to think straight into her mind, but all I find is an ocean empty of her. My only buoy is the painting.

Without her, it’s all a circus. The tents are scattered and empty and the sky is gray, and the canvas flaps slap a staccato chorus in the wind. It looks like rain. Old popcorn cones and greasy soda cups and crepe paper spread across the ground like confetti, and all that waste will get soaked and disintegrate and turn to mud. And yet the painting remains. Dear Circus Master, won’t you let me try again? I’m balancing all the chairs of the world on the tip of my nose. Have you forgiven me yet, will you come back? I’ve saved you a seat.

—

The prologue was always in question.

But I didn’t cut it until the copy-edit phase, only three months before my September pub-date.

Months before that, back in January as we were entering into the last round of edits when review copies were to be printed, I started to freak out. This was my last chance to have other eyes on my book. I emailed my novel to a handful of good friends (mostly writers) with specific questions including a kind of poll: Should I keep the prologue? What does it do for you? What is it failing to do?

My argument for the prologue (and it was always an argument) was that it was my way of teaching a reader what kind of book this was going to be: a weird one. My novel is a two-voice narrative told by Claire, a Greenwich Village housewife, and West, a present-day data-miner with schizophrenia. Though we open on Claire in 1959, I wanted to guide the reader into the novel with West’s voice to emphasize the power he has over the structure of the book and its storytelling devices. I wanted to present his unordinary mind up front.

Most of my readers encouraged me to keep it, but not enthusiastically. It set the tone and it didn’t bump them, they said. But did it draw them in? Did it do all the work I wanted it to do? Or was it just a lot of throat clearing?

My mother thought so.

While I was writing, I often thought of my aunt as a test subject for my novel. I was looking forward to giving it to her. If my book could be for her as well as my more literary friends, both groups perhaps gleaning something different from the pages, then I had done my job. She passed away last summer and I never got to show it to her. The book is dedicated in her memory, as well as two other women who are no longer with us and who were always proud of me as a writer.

Luckily, I have my mom. She skimmed the prologue, didn’t know what to make of it, said plainly that it didn’t add anything and that she didn’t get into the story until the start of Part One. And from there onward, she loved it. This is a woman whose review of my previous work included phrases like, “too weird for me,” so I trusted she wasn’t just blowing hot air about the remainder of the novel. But the prologue left her with the feeling that maybe this book wasn’t for her after all. I know my aunt would have felt the same.

I teach my students that information about a character (backstory, thoughts, philosophies, etc.) won’t stick with the reader until the reader can really see and feel the character come alive, usually through scene. My prologue relies completely on West’s voice. There isn’t a character interacting in a scene to attach that voice to. And it raises questions that won’t be answered for many pages.

In the end, I decided that, to many readers, the prologue would act as more of a barrier than a well-lit threshold. I want my mother and her friends to find my book accessible, moving, and unsettling. But to get them to read it at all, I couldn’t first scare them away.

My editor was thrilled. He had suggested cutting it long ago, but had never pushed the matter. I think he trusted I’d get there on my own. Some of the sentences and sentiments from the prologue found homes in other West sections. But some darlings were cut for good, like the circus imagery at the end. There just wasn’t a place for it in the novel. I’m happy it found a home here.

Though we visit West’s abstract thought-processes later in the novel, the story starts in 1959, in Claire Bishop’s fancy apartment as she is sitting for her portrait. We are grounded in place and time, as it should be when you invite strangers, readers, into a new world. Above all, I want readers to be able to connect and relate to West, despite, or because of, his difference. I did not want to turn a reader off to him or the book due to lack of clarity. Rather, I want to trick them, I mean gently nudge them, into trusting a different kind of voice.

Carmiel Banasky is the author of the novel, The Suicide of Claire Bishop (Dzanc 2015). Her work has appeared in Glimmer Train, Slice, Guernica, PEN America, The Rumpus, and on NPR, among other places. She earned her MFA from Hunter College, where she taught Undergraduate Creative Writing. She is the recipient of awards and fellowships from Bread Loaf, Ucross, Ragdale, Artist Trust, I-Park, VCCA, and other foundations. After four years on the road at writing residencies, she now lives and teaches in Los Angeles.