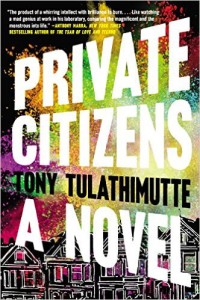

Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens is a searing and savagely smart dissection of the life and opinions of a group of San Francisco millennials: bipolar autodidact Henrik, ruthless aspiring writer Linda, porn-addicted romantic Will, and hazily embattled activist Cory. With relentless intelligence and wit—and prose that’s earning comparisons to David Foster Wallace—Tulathimutte examines his characters’ anxieties and aspirations, vanities and self-hatreds, and the gap between private consciousness and public personae. I emailed with Tony to talk about the challenges of taking on a generation as a fictional subject, the Glass-Steagall Act, dirty freeloading hippies, and why novelists are so afraid of writing about the Internet.

Tony Tulathimutte’s Private Citizens is a searing and savagely smart dissection of the life and opinions of a group of San Francisco millennials: bipolar autodidact Henrik, ruthless aspiring writer Linda, porn-addicted romantic Will, and hazily embattled activist Cory. With relentless intelligence and wit—and prose that’s earning comparisons to David Foster Wallace—Tulathimutte examines his characters’ anxieties and aspirations, vanities and self-hatreds, and the gap between private consciousness and public personae. I emailed with Tony to talk about the challenges of taking on a generation as a fictional subject, the Glass-Steagall Act, dirty freeloading hippies, and why novelists are so afraid of writing about the Internet.

—

Jennifer duBois: How did you arrive at the decision to follow these four characters’ perspectives? Were you casting the book with an eye toward capturing a particular social milieu, or did the individuals come first?

Tony Tulathimutte: As it goes with most of my writing, intention has little to do with it and desperation everything. In 2008 I was trying to resuscitate a writing habit that had been vegetative for two years, and after months of work I had managed to get four characters in a car, and had enough to say about them that, no matter how much I rewrote it, left me with a 40-page character study with no plot, action, or dialogue. So I just called it “Prologue” and went on from there. I chose the setting only because it was the time and place I was living in at the time, which I figured would supply lots of osmotic material, which it did.

JD: Your characters are all Millennials, yet some feel more distinctively Millennial than others. Cory’s storyline seemed like it could have played out similarly in another era—her thwarted idealism reminded me a little of Dorothea Brooke from Middlemarch—whereas Will felt explicitly situated in the present; I had the sense not only that his plot could not have played out in an earlier era, but that Will as we know him could not quite have existed. How did you conceive of your characters in relation to their generation?

TT: You’d be amazed, or maybe not, at how hard I tried to write about anything but Millennials. This was because I figured that our hash had been settled, that the jury’s verdict had come in, and not in our favor.

It took some time before I understood that Millennials were so maligned simply because they were young enough that they hadn’t been constructing the narrative themselves. It was the older generations who were doing all the maligning; and has any post-WWII generation not spewed contempt for what came after it, deriding it as lazy, entitled, narcissistic, misguided, and soulless? Dirty freeloading hippies, “Me Generation” boomer yuppies, disaffected Gen-X slackers, and now coddled, sexting Millennials—I think it’s mostly that young people who don’t have to defend their nation at war are considered privileged just for availing themselves of modern conveniences and forming their own values. (And we’re still fighting wars, too.) Of course the funny thing is that much of what is deemed a generation’s failings are natural outcomes of socioeconomic problems inherited from the disapproving older generation. Oh, you want me to move out of the basement, Dad? Well stop fucking with Glass-Steagall and give me back my manufacturing base.

Add to that the usual alienation of new music and slang, of not getting Tumblr or Snapchat or whatever, of course you’re going to hate younger people. The oldest Millennials, like me, are now in their thirties, so we’re already at the point where we’re seeing the same contempt for teen YouTube celebrities and hoverboards and VR, plus ça change. Probably because he just died, it seems to me that David Bowie, an era-mooting figure if ever there was one, gave us the pithiest version of the-kids-are-alright: “And these children that you spit on, as they try to change their world / Are immune to your consultation—they’re quite aware what they’re going through.”

That said (swear to god I will eventually answer your question), now that we’ve come up and are beginning to fashion our own collective narratives, some people indulge the opposite and equally misguided impulse to gleefully assume the generational mantle, to mythologize and identify by your cohort—“Only 90’s kids will understand,” and so on. Both they and the naysayers end up painting a pretty deterministic picture of identity, where the lowest common denominator becomes the most definitive, and the basis for community.

The problem is that this view of identity is so incentivized. The term “Millennial” was coined in 1991 by two demographers and has since been leveraged by trendspotting media, political strategists, and marketing consultants, who all learned the wrong lesson from Marcuse and have an interest in designing and segmenting targetable identities. To see a “real” self reflected in what you buy, who you vote for, the hobbies you pursue, or the media you consume grants you membership into communities, allays your anxieties about self-actualization, and gives you something to brand yourself by on social media. In that sense, to sheepishly or proudly buy into a prefab Millennial identity—or, at the rate that radical positions are being co-opted, any identity at all—is to wind up doing the dark beast’s fell bidding, even if it’s for a good reason.

The project of trying to sum up or crystallize a whole generation travels in precisely the opposite direction from the novelist, who’s concerned with individual difference. You’re trying to draw out and particularize the huge chorus of voices within each character, instead of identifying an entire cohort of people by relatively superficial traits. I can’t deny that a cohort shares qualities in common; it’s just that those qualities are usually the least interesting things about us. My characters are reconstitutions of myself and some people I knew, and any perceived generational affiliation is a side-effect of that. At the same time, I know this book will be taken as a book about Millennials whether I like it or not; I mean, the M-word is right on the jacket copy. I just hope no one drags me for neglecting X or Y Millennial experience when my only goal was to write about this handful of privileged characters in San Francisco.

Sorry, here’s my answer. Henrik and Cory both feel at odds with their generation, in spite of whatever privileges they carry within it; Cory’s professional duty to cater to “young people” has made her resent them—a resentment she’s nonetheless implicated in. With Will, you could say that his storyline is so contingent on the specifics of modern technology that he might not have been conceivable in earlier decades, but you could imagine a historically analogous role for him, as an alcoholic surveillance-happy jealous boyfriend: private eye, maybe. If anything would’ve kept Will from being portrayed as a fictional protagonist, it’d likely be his Asianness. And Linda, for whom identity is a sensitive issue, aggressively resists all characterization from without, declaring: “Who gave a fuck about the generation?”

JD: One of the most arresting aspects of Private Citizens is the way it blends intimate characterization with kaleidoscopic social observation. We stay deep—nearly entombed—within our narrators’ minds, yet emerge with something bigger than the sum of their respective experiences. Did you experience any tension between capturing your characters’ inner lives and reflecting the world around them? How did you negotiate that?

TT: The dichotomy you’re describing, which is plastered in large white letters across the book’s cover, is a traditional division I’ve thought about a lot since a high school French class I took called “The Individual and Society,” where we read Balzac, Voltaire, Sartre, Ionesco and Molière, and the model they implicitly endorsed was essentially this: you’ve got a bare, pure human soul, contesting against or crushed by or fleeing the forces of the society it’s in. It’s French guy vs. the world.

TT: The dichotomy you’re describing, which is plastered in large white letters across the book’s cover, is a traditional division I’ve thought about a lot since a high school French class I took called “The Individual and Society,” where we read Balzac, Voltaire, Sartre, Ionesco and Molière, and the model they implicitly endorsed was essentially this: you’ve got a bare, pure human soul, contesting against or crushed by or fleeing the forces of the society it’s in. It’s French guy vs. the world.

While I was working on my book I was jokingly describing it as an antisocial novel, since even though it has all the trappings of a traditional social novel (subculture tourism, contemporary urban setting, multiple POVs), the characters spend most of their time either alone or so retracted into their thoughts that they may as well be. I don’t think there’s any tension, though, because there’s no clear division. My cog-sci training might bias me in my belief that what we do, what we think about, and how we feel about it is mostly not up to us and is heavily determined by our circumstances—see any number of studies on cognitive priming, groupthink, primacy and recency, the observer effect, etc.

This seems like a weird position for a novelist because soul-plumbing and moral accountability have been the whole deal for so long. But it makes no sense to try and convey individuals as brains-in-vats without reference to their world, whether it’s as stuffed as a Zadie Smith novel or as barrenly metaphysical as a Beckett play, because the meanings of actions and thoughts only come across relative to their context. This is the question that Henrik deals with, having been raised poor and without a community, therefore lacking much of a social context. It’s no accident he looks for solace in hard determinist philosophy and physical science: you don’t have to angst over personhood if you can convince yourself you don’t have a real say in the matter, that you’re just a biochemical phenomenon and consciousness is a funny joke.

JD: Generational eras are defined by fundamentally different kinds of change, I think—the ’60s altered reality, the ’80s altered attitudes toward reality, and the ’00s altered the relevance of reality. Those first two shifts have been extensively explored in fiction, but contemporary novelists seem pretty squeamish about tackling the Internet; those that do tend to approach via satire or fabulism. Private Citizens might be the first realist novel I’ve read that deals with the Internet so substantively—exploring not only its broad implications for society, but its meaning in the lives of individuals. What are your thoughts about taking on the Internet in fiction? Do you have a sense of why many novelists seem hesitant to do this, and did you experience any of this hesitation yourself?

TT: The Internet is scary for some novelists because its constant mutation, in form as well as content, makes a fast and nebulous target for a very slow medium; by the time we can step back and digest the broad impact of, say, Google on people’s lives, we’re already onto freaking out about smartphones. We get a grip on the mysterious anonymity of Craigslist dating ads, but then it morphs into OKCupid and Tinder. (My book takes place the year the iPhone was released, not a moment too late.)

To my mind there’s nothing trickier than usual in writing about the Internet, especially if that’s where you live. I’d been working as a UX consultant in Silicon Valley when I started, and felt I had enough of a head start to maybe not be completely eating dust when the book came out. I was wrong, but by the time I was three or four years into writing it, relevance and immediacy had become the least of my priorities. It doesn’t bother me that some of the Internet technology I wrote about is no longer used any more than it bothers me that there are chariots in Ben-Hur. Why spend seven years working on something that’ll go obsolete in another seven? Leave that to technology.

JD: Private Citizens is relentlessly specific about the world its characters are actually living in—there’s no attempt to avoid dating the novel in the eyes of future readers—and in some ways, the book already feels like a snapshot of an era and a city that don’t quite exist anymore. Did you conceive of Private Citizens as a time capsule while you were drafting it? Did San Francisco’s dramatic change over the course of your work shape your sense of the book you were writing?

TT: The San Francisco in my book is a relic. I think I heard that median rent doubled in three years after I left. When I last visited in 2013, Dolores Park was a construction zone and everyone at my favorite bars was wearing the T-shirt of the tech company they worked for. There aren’t many places for people to be driven out, since commuting to the city from Oakland on the BART is a lot harder than commuting from Brooklyn, so the influx of money caused a pretty nasty greenhouse effect. I lived there at a time when you could still say it was undergoing gentrification, instead of endgame capitalism. Case in point, on Valencia Street, the battle line of gentrification that divided the Mission from the tech-millionaire burb of Noe Valley, there used to be a restaurant that had replaced a KFC—it was winkingly called Spork. Now Spork is finito and it’s just a regular sushi place with $14 rolls.

Like I said, everything gets way chill once you accept that up-to-the-minute cultural reportage is a better fit for the Internet and TV. Even if that was the aim of this book, as it is in a Tom Wolfe or Jonathan Franzen novel, it just becomes a snapshot in a few years anyway. It didn’t change my approach to the book much, except that at a certain point I wasn’t relying on my surroundings for detail anymore, but from memories of the recent past, which, now that I’ve written all over them, are barely even memories anymore.

Tony Tulathimutte has written for VICE, N+1, AGNI, Salon, New Yorker online, Threepenny Review, and others. He is a graduate of Stanford University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and has received an O. Henry Award, a Truman Capote fellowship, a MacDowell Colony fellowship, and the Michener-Copernicus Society of America Award.

Jennifer duBois is the recipient of a Whiting Writer’s Award and a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Award. Her first novel, A Partial History of Lost Causes, was the winner of the California Book Award for First Fiction, the Northern California Book Award for Fiction, and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Fiction. Her second novel, Cartwheel, was the winner of the Housatonic Book Award fiction and was a finalist for the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Award. She teaches at Texas State University.