The First Voyage of Amerigo Vespucci

The First Voyage of Amerigo Vespucci

In the beginning, so much depended upon pine nuts and morels. No, not buffalo as you’ve been taught—those came much later. In the beginning, it was the giant beaver whose shadow darkened the North American food chain, and who lugged his heavy beaver tail from state to would-be state as he fled the arrows of native hunters. Then corn was planted. The seeds of future books on improper diet and misuse of natural resources were sown in some southwestern pueblo. A bird cried out over an empty canyon. And all along the Mississippi, the gentlest beings drank deep of the fog, thanking their maker.

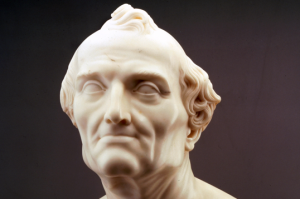

Then came Amerigo Vespucci, big as a house. He was taller than a Trojan horse and marbled as Michelangelo’s David, who was, it so happens, also born in Florence. He surprised the world, a merman bursting from a tall cake, strong jawed and near nude. Men and women fell in rap- ture at his feet, so it was told.

Yet Vespucci was wed to nothing, in 1497, so much as to the bank of the Medici family in Seville. While the legend-to-be stocked ships for other explorers and calmly counted his coin, some scoundrel forged a missive and signed it as Vespucci. And so a false, fictional Vespucci was born, and visited the New World. He scanned the rocky shores, the seemingly endless land, the forests and the pine nuts. He saw the natives sleeping carelessly in hammocks or perched in sweatboxes, smoking, considering the stars. He saw how vulnerable they were. What a treasure to leave unguarded! The faux Amerigo trembled in banker’s delight. The Vespucci who wasn’t really there leveled his sights on poor Chris Columbus and, shaking a fist at the sky, declared, “She will be mine.”

A continent is always a woman like that. The true Vespucci married late in life because, it was rumored, the wretched landform always got in the way. He hadn’t asked for such responsibility—parent to a name, a nation, a people—and he didn’t want it. He’d wanted nothing more than a humble life of service with some time spent on the ocean and upon his return a saucer of warm soup at the head of a long table. He’d wanted a son.

But you can’t always get what you want. A ship creaks in the nightmares of Amerigo Vespucci, and a sail snaps to; an unknown land mass looms on the horizon, ever closer, come to make him king of a country called darkness.

The Second Voyage of Amerigo Vespucci*

We found this land to be all drowned and full of very great rivers. There we tried in many directions to see if we could enter; and owing to the great waters and rivers, in spite of so much labour, we could not find a place that was not inundated. Only four boys remained in the canoe, who were not of the tribe. They had been castrated and were all without the virile member, and with the scars fresh, at which we wondered much. Having taken them on board, they told us by signs that they had been castrated to be eaten. We then knew that the men in the canoe belonged to a tribe called Cambali, very fierce men who eat human flesh. We made friends with them, and many of us went with them to their camps in great security. We ate a great many of the boys, as they were in season. It is a very good fruit, pleasant to the taste, and wholesome for the body. The land abounds in their articles of food, and the people are of good manners, and the most peaceful we have yet met with, and every day new people from the interior came to see us, wondering at our faces and the whiteness of our skins.

*Some sections taken from The Letters of Amerigo Vespucci and Other Documents Illustrative of His Career. Translated with notes and an introduction by Clements R. Markham. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1894. Early Americas Digital Archive, University of Maryland.

Ptolemy’s Cat

It is a little-known fact that Ptolemy kept a cat whom he loved, it is said, above all creatures. The cat was white as moonlight on the steps of the Parthenon. He was a born mouser. Regularly he delivered gifts of dead or maimed birds to Ptolemy’s doorstep or left them tangled in the bed sheets—their bloated bodies raked, burst, leaking crimson on the Egyptian cotton. A shower of grey and white feathers marked the path to the mapmaker’s door. Ptolemy found death distasteful as a rule, but the animal’s loyalty charmed him. So he started killing things in re- turn. First he killed the reputation of a local merchant by accusing the man of fraud. Next he aborted several voyages of discovery to Asia simply by marking them on his maps, “Here be dragons.” He murdered textual purity by writing the world’s first piece of music theory. He began to take joy in it. Between Ptolemy’s legs, the cat drowsed at night with his white limbs outstretched. The astronomer’s hand moved absently through his warm fur.

Almagest, as the feline was called, died in his owner’s arms at the age of twenty-three. Ptolemy’s wife, who had ever been jealous of the cat, drank a glass of whiskey and smiled. Ptolemy said nothing; he sank his spade. A full moon rose over the uncharted continent.

The Third Voyage of Amerigo Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci to Lorenzo Pietro Francesco di Medici:

These land masses are much larger than we anticipated. I mapped the stars, as you wished—Alpha and Beta Centauri and Crux, the Southern Cross—the stars forgotten by the Greeks. I stole all the pearls. We set out on the 14th of May 1501, and we sailed forever, for twenty months. Have you any idea what a ship smells like, full of men, after twenty months? No, certainly you don’t. You’re the type to delegate. We set out to discover new countries in your name. We found the Ethiopic Promontory, as Ptolemy called it; now it’s just Cape Verde. We saw the region of land between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, north of the equinoctial line. A black race inhabits that country, and they did not care for us. I’ll spare your lordship the details, but I lost Ferdinand II, my favorite personal assistant. I blame you for this.

The land is too large, with more people than our Europe has, and more animals. It is drowned in waters and hairy with trees. It has no need of us. The people wear no clothing, because they have no need of it. What can I say! The women are nude. Their bodies are bare and lascivious, yet comely. Wild as you can imagine, these women are. They prefer pleasure to the consideration of philosophical matters. The people live for a hundred years and seldom ail.

We’ll change all this, won’t we? Cloth and government, order, and a name for every star. I stole all the pearls like you said. To Him be the honour and glory, and the grace of the action.

Terra Ignota

My name is Amerigo Vespucci.

Sometimes I think I’m nothing but my name. Sometimes I think, well, I’ve made that name, I’ve earned it—I explored the continents, mapped the New World, and the name is mine now like a bright pearl lodged in an oyster’s dark mouth. When the fever ebbs, I know the truth. My name was made in error. A fool forged a letter. One could blame it on the mapmaker, but he only followed a false prophet—as we all do, when we seek to find anything truly new.

I lie here behind closed drapes, listening to the voices of children playing on the cobblestones outside. Flies clutch at the netting. The day is hot. Sevilla is a finger of land intruding on the inlet of my illness. I should warn the children of forests, of flesh-eating men, and women so lovely you wish you’d disappear in them and never go home, but my throat is too dry. I am dying. Where I go I cannot take my name.

KELLY RAMSEY studied poetry at the University of Virginia and earned an MFA in fiction writing from the University of Pittsburgh. She lives on Fishers Island, New York, where she is co-director of an arts collective and fellowship program called The Lighthouse Works.