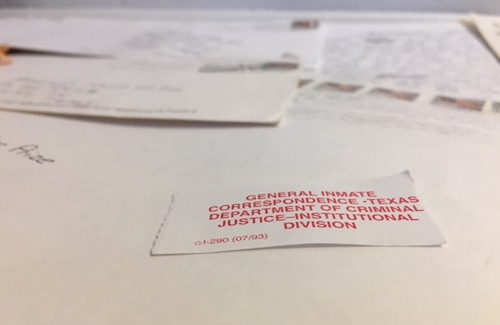

Submissions to The Insider Prize—a writing contest for incarcerated writers in Texas, which we held for the first time this year—came to us in envelopes of many sizes. Most had been previously opened, with a red TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS stamp on the inside of the lip of the envelope that had been taped shut after an inspection. Some were composed on a typewriter. Others were handwritten.

Submissions to The Insider Prize—a writing contest for incarcerated writers in Texas, which we held for the first time this year—came to us in envelopes of many sizes. Most had been previously opened, with a red TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS stamp on the inside of the lip of the envelope that had been taped shut after an inspection. Some were composed on a typewriter. Others were handwritten.

Like many literary journals, American Short Fiction accepts only electronic submissions. And while much of what I read comes from a screen, I often forget the human component to words, to the process of physically creating the letters and shapes that appear on a page. With these submissions, we felt the labor and work that had gone into the creation of words, and worlds. We physically held them in our hands. Receiving these submissions directly from the writers, I was reminded that literature is, at heart, epistolary.

These submissions reminded me just how many people are sitting in prisons across Texas, some of whom have been incarcerated for longer than I have been alive. This contest—inspired by Deb Olin Unferth’s relentless dedication to her students and Pen-City Writers, a creative writing certificate program at the Connally Unit in Kenedy, Texas—is an effort to remember. Chosen by Lydia Davis, these winning pieces intertwine loss and longing with a sharp, melancholic humor. American Short Fiction was honored to have Davis judge our inaugural Insider Prize, which she did with discernment and also phenomenal class and generosity, writing long, thoughtful, individualized letters back to each of the finalists. We remain exceedingly grateful for her participation.

Submission guidelines for the 2018 contest will be available shortly.

— Emily Chammah, Assistant Editor & Co-director of the Insider Prize

WINNER—CATEGORY: FICTION

Pushing Up Daisy

Keith Sanders

The first coherent thought she had after waking up was: Goddamn you, Glenn. What happened? Why the hell am I awake? Daisy’s second well-formed thought was that there shouldn’t be. There weren’t supposed to be any thoughts. Wasn’t in fact, supposed to be anything at all.

But maybe, just maybe, this was how it’s supposed to be. This thought gave Daisy some hope. How could she know what to expect anyway? Nobody could, not even Glenn. So maybe she wasn’t supposed to distinguish between before and after. Or it’s different in a way she wasn’t yet able to discern. Or: maybe nothing’s supposed to be different. The same wetness between her legs (always, always that reminder of her incontinence), the same persistent ache in her ankles and knees, the same uncontrollable bouts of IBS, all the same nagging, tiresome bullshit piggybacking on this 61-year-old thing people called a body was supposed to just continue and continue for—no. Who was she trying to fool? There didn’t seem to be any difference because there wasn’t any. Goddamn hope’s as treacherous as despair, Daisy mused.

And then she opened her eyes.

Daisy sat in the same recliner, inside the same Gulfstream trailer, as the night before. The pre-dawn light seeped in through the windows, suffusing the Gulfstream’s interior with a wan, orangish hue. She looked down at the inside of her right arm. The needle was still there, nestled deep within a vein. Not a junkie’s thin hypodermic, but an ice pick-thick vein penetrator like those used with IVs in hospitals. Or blood donor clinics. Which was where Glenn had said he got this one. He’d also said that he never in his fifty-eight years of existence ever “purloined a single item.” Glenn used words like “purloined.” Daisy didn’t care what kind of words he used because she thought he was full of shit either way. And had told him so.

Clear, pliable tubing was affixed to a rubber seal at the back end of the needle. Daisy allowed her eyes to trace the tubing back to its source: a makeshift IV bottle attached with duct tape to an upright wooden broom handle. It was one of those green-tinted two-liter plastic soda bottles that Glenn had repurposed for the occasion. If Daisy looked close enough, she’d be able to see that the IV still retained some of the clear liquid Glenn, late the night before, had poured into it. Glenn had promised her that it would work. Assured her that the device was “sufficiently detrimental to one’s well-being,” that he was assiduously following the instructions he’d found on a website dedicated especially to the construction of such devices.

* * *

Glenn. Obese Glenn, who could sit down only as an overly large person could: all at once. Rotund was how Glenn described himself. “Round, you mean,” Daisy had clarified. Round ruddy face with round wire-rimmed spectacles fronting a bowling-ball head stoutly rooted on top of a round body. Glenn the Round, that’s how Daisy described him.

Glenn had come by the Gulfstream for the first time three days after she’d moved here. “Here” being a trailer park in Arizona, where she’d been living for the past two years. After Daisy had saved enough money to quit her job, she bought a (very) used Gulfstream (though still gleaming like a shiny new dime) and drove it to the only place where she could both live off her monthly Social Security checks and be as far away from other people as possible: a torrid patch of desert in the southernmost corner of Arizona. Glenn lived in a trailer several lots away and had said that three days was the appropriate amount of time to wait before welcoming a new neighbor. Daisy told him that she was neither “new” nor a “neighbor,” that she didn’t want any welcoming, and promptly shut the trailer’s only door in his face. Undeterred, Glenn had returned every day and knocked on her Gulfstream’s door. After two months of “Go away” and “I don’t want any visitors, goddamnit,” Daisy had finally relented and let him inside. She would never admit it, but Daisy had found his polite persistence quite flattering. It wasn’t something she was used to.

Daisy had spent forty-three years waitressing at a truck stop situated on a well-traveled interstate near the meager flanks of a speck of a town in rural Texas. Working sixteen-, sometimes eighteen-hour shifts, six days a week, Daisy had to wait on, serve, and contend with bilious crowds of long-haul truckers. She had to endure a ceaseless mass of unwashed bodies in rancid, sweat-stained clothing, with fetid breaths and clumsily groping hands. Their interminable presence created a tangible, acrid residue in the air she had to breathe, in the spaces she had to move around it. Waiting on truckers for a living does something to you, Daisy had once tried to explain to Glenn. You can be around people like that for only so long before they start to crowd out the you in your head. And if you’re no longer you, then who the hell are you?

“You are you, Daisy, and no one else,” Glenn had answered. “Because you cannot alter who you are.”

“Weren’t you listening? I didn’t say that I could. They did the changing to me.”

Glenn was sitting on the sofa, next to Daisy in her recliner, and he leaned forward, but carefully because of his bulk. “If you cannot alter the essence of your being, and you are indeed a person, no? Then it follows that people also cannot alter your essential being.” He leaned back, point made. “I am also confident in your ability to apprehend my reasoning.”

“What the hell does that mean?”

“Only that you are astute enough not to deny other people the opportunity, and pleasure, to engage your wonderful personality.”

“Don’t be such a prick. You know that I don’t like other people.”

“Correction: you take issue with their presence.”

“Right now it’s one and the same.”

“But you like me, no?”

“I tolerate you.”

“Because my presence attenuates your loneliness. As it—”

“Fuck you, Glenn. All the way to hell and back. I told you: I am not lonely. You never listen to me and always go off half-cocked on some—what the hell are you smiling at?”

“‘Loneliness does not come from having no people about one, but from being unable to communicate the things that seem important to oneself, or from holding certain views with others find inadmissible.’” Glenn quoted.

“What the hell was that?”

“No, no. Not a what, Daisy. A who. I quoted Jung. Carl Gustav Jung? No? How would you say, ‘it doesn’t ring any bells?’”

“What is he, one of your lovers?” Daisy spat sarcastically. Glenn laughed. Her truculent attitude towards his homosexuality (his “sexual heliotropism,” as he preferred), never discomfited him. Quite the opposite, in fact: he adored it, just as he adored everything about Daisy.

“Herr Jung? Oh no, Daisy. He is much too old for me.” Daisy glared at him. “No? Do you not, ‘get the joke,’ as you say? Jung expired in 1961.”

* * *

Last night, after Glenn had finished putting the ersatz IV together, after pouring what he vociferously claimed was dissolved rat poison into the repurposed soda bottle, he had suddenly stopped prepping Daisy’s arm for the ensuing “delicate puncture.”

“Why, Daisy? What is your reasoning for wanting to do such an act as this?”

“It’s none of your goddamn business why.”

“No? Despite the fact that I am assisting you?”

“You promised to help and not—”

“Correct. But—”

“And not pester me with any fucking questions about it.” Glenn held the needle several inches above Daisy’s arm, waiting. “Because I’m tired. Okay?”

“Tired? Of what?”

“Everything. Nothing. Tired of being fucking tired. Satisfied?”

“No.”

“Of course you’re not.”

“But that is not a sufficient reason, Daisy. For sleeping twenty-three hours a day, perhaps. But not this.”

“I didn’t ask you to interrogate me, goddamnit. You’re here to help me. That’s all.”

“And I am.”

“What the hell does it matter to you anyway? Why is it so important for you to have an explanation, to have a fucking reason for everything? I don’t need one.”

“And me?”

“And you what? I’m not asking you to join me, goddamnit.”

“No. Why am I present, Daisy? Here, now, I mean.”

“Because I asked you to—”

“Correct. But I mean, if you are so steadfast in your determination, then why do you require my assistance? What is the purpose for my presence?”

“Are you backing out and reneging on me? Is that what you mean?”

Glenn had answered by inserting the needle into Daisy’s arm.

Earlier, he had crimped the tubing and held it together with an old clothes pin of Daisy’s to keep the contents of the IV from flowing freely through the needle’s opening. Glenn removed it now. The liquid swiftly traversed the length of the clear tubing and into the needle’s butt end, into Daisy’s vein and body. Both avidly watched the flow. Daisy’s face registered a touch of fear and uncertainty overridden by grim determination, while Glenn leaned back and smiled grandly at Daisy. She saw him smiling and then smiled, too. Daisy hadn’t felt such happiness in a long, long time.

“Why are you helping me with this, Glenn? Helping me with—”

“Close your eyes, Daisy.” She did. “Good, good. Are you listening? You will begin to feel sleepy. Do not attempt to resist. Give yourself over to the process. Give all of yourself, Daisy. Better?”

“Answer me, Glenn. You starting asking this why shit.”

“Because you are my friend. Why else?”

* * *

The Arizona sun crept above the desert horizon, making its frery entrance into the Gulfstream. Anxious to get up and pull the curtains tight before she became engulfed in a flameless inferno, Daisy yanked the needle out of her arm. She tore a page out of last week’s T.V. Guide and sopped up the blood that welled out of the angry red hole. Only then did Daisy notice that liquid flowed out of the needle in a steady stream. She found the clothes pin and clamped it to the tubing to stanch the flow. Daisy forgot that Glenn had crimped the tubing first, so the liquid continued to fast-drip out of the needle’s opening.

Daisy brought up her other hand and held it beneath the dripping needle. One drop. Then another. As each dew-like drop formed a shimmering bead at the needle’s tip, it grew until it reached a critical mass, then shuddered slightly before detaching itself and falling into Daisy’s cupped palm below. Another drop. Then another. Daisy blinked at the sun’s encroaching luminosity. She desperately wanted to extinguish its unwelcome refulgence, but the procession of droplets transfixed her. Each drop formed in the space vacated by its predecessor, as if sacrificing itself so the next one could emerge into the light of the world. So the next one could live, however briefly.

Soon Daisy had a small puddle of liquid cupped in her palm. She brought her hand up to her nose and smelled the suspiciously clear liquid. Nothing. Not a goddamn thing, Daisy thought. Then, as if on its own accord, her tongue flicked out from behind her lips and tested the puddle’s shallow depths.

It tasted salty. Like tears.

Keith Sanders is a playwright and writer doing life in a Texas prison. In his 29 years of incarceration, Keith has earned an AA, a BS, and a Master’s in Literature. Two of Keith’s plays have been professionally produced and staged, and he’s won First Place in Drama in the PEN American Center’s annual PEN Writing Awards for Prisoners three times in the past ten years. “Pushing Up Daisy” is adapted from a full-length play of the same title. Keith welcomes comments and correspondence regarding his writing. He can be reached at:

Keith Sanders #529987, Ramsey Unit, 1100 FM 655, Rosharon, TX 77583.

WINNER—CATEGORY: FICTION

WINNER—CATEGORY: FICTION

Lechuza

Edward J. Monroe

My father showed me how to fly a kite. It was a cool autumn morning, and we were in a meadow near a park.

“Okay, now hold the kite up in the air with one hand and run as fast as you can. When you feel it begin to lift, let go of the kite, not the string. That’s it. Now stop. Hold her steady. Now pay out some more line. Good. Wow, look at her fly! Good job.”

Side by side, we stood in silence for a while, staring up into the yellow, plastic, turkey vulture face of the kite, sipping and dipping erratically on the higher currents of the wind. From within the delicate balsa framework, two large, red googly-eyes peered down at us. I could feel dad’s unseen smile as surely as I felt the warmth of the morning sun and the cool fall breeze on my face and hands.

Tiny furrows on my thumb and forefinger burned as the kite string stripped from the spool in my other hand, the wind yanking its yellow passenger higher and higher into a perfectly blue sky. The spool stopped abruptly, the string exhausted, but the kite kept going, leaving me with an empty cardboard cylinder in one hand. The kite was only a speck, soaring away over the nearby forest until [the] speck in the sky disappeared. I ran after the kite until I could no longer run and the searing pain in my side doubled me over. It was no use. I fell crying, face down in the grass. My kite was gone forever.

That night in bed, I lay awake, wondering where the kite went, how far and how high it had flown. When I fell asleep, I dreamed I was floating, light as a feather, carried away on the wind. Then I was gently falling, drifting downward, settling softly into the cool, pale green current of the Guadalupe River and bobbing gently over rapids and through little whirlpools, lying on my back, watching cottony clouds morph into great icebergs, evaporating into wisps of silent steam.

My father became a grandfather, and even well on in years became the center of controversy in the family. We worried about his welfare and safety. The consensus was that he drank too much—sometimes until he fell down. We all took turns driving over to his place to check on him, concerned he might fall and hurt himself badly and not be able to call for help. We told ourselves his excessive drinking was because he missed mom so much. He was unable to move past losing her. It was tough on him; tough on us. None of us knew what to do or even what we should do. We considered the option of putting him into an assisted living center.

When my brother invited me to go fishing one day, I knew his real motive was to discuss dad’s condition. With my young son and his beloved little dog GiGi, we met my brother at a favorite spot on the banks of the Guadalupe. My brother and I talked sparingly for a while because my son was in earshot. The youngster soon grew bored and went off to catch grasshoppers. In short, almost foreign sounding voices, my brother and I talked about dad’s situation. There were no easy choices. Nobody in the family wanted to send dad away, but if we did nothing, something bad could happen to him when he was home alone. Would we be able to live with ourselves then? Family used to take care of family. Why didn’t we have time for each other anymore?

We fell silent for many moments, each of us obviously struggling to come up with answers, perhaps too proud to admit we didn’t even know what the real question was.

My son returned and sat down on the damp sand between the two of us. He was clutching a plastic bag full of kicking grasshoppers, periodically thumping the bag with his thumb, trying to get the contents to settle down. I stood to stretch my legs, and it suddenly occurred to me. “Where’s GiGi?” My son shrugged and stuck out his bottom lip, concentrating on the grasshoppers in the bag.

I whistled and called the dog’s name. “Stay here with your uncle. I’m going to look for GiGi.”

What I really wanted to do was take a walk, take time to be alone with my thoughts, maybe sort it all out. I had a hollow feeling inside as I numbly followed the river deeper into the woods. Keeping an eye out for GiGi, I occasionally whistled and called, but mostly I was lost in reflection.

I came to a place in the woods I had never been before. All the trees on both sides of the river looked the same—dead and bare. It was eerie how suddenly the forest changed from a living, breathing thing to a desiccated cemetery of trees. Like ancient tombstones, the whitened tree trunks jutted far upward at odd angles from the ground. Perched in the skeletal branches were multitudes of vultures, staring down at me with great, coal-black, unblinking, emotionless eyes. I tried to shake their resolve by flapping my arms and yelling at them. None of them even flinched, their icy composure sending a chill completely through me.

I thought of witches gathering in a secret coven to hold Black Mass. I’d heard such stories as a kid. Lechuza, they are called in Spanish, half human, half bird. It is said that if someone whistles to one, it will follow him. They are perceived as omens of death. If someone sees one of them, someone close to him will die. And if one hears a Lechuza hoot his name, he will know that his time has come.

Deep in those woods, surrounded by sinister-looking scavengers, I began to feel it would be a good idea to quietly turn and go back, and it was then I heard a strange rustling sound high above. Instinct made me turn and look up. There, stubbornly clinging like Spanish moss from a forked branch was a tattered, torn and faded old piece of plastic that might have been yellow at one time, chattering mindlessly in a sudden breeze. As the wind died, the piece of plastic ceased its hectic dance and dangled, slowly revolving form side to side. Looking back at me was the faint impression of two large googly-eyes. Like the abandoned remains of a corpse, the ghost of my childhood story looked down on me and answered many questions. GiGi snuffed around my shoes.

When I returned to my son and brother, both had tired of fishing and were ready to leave.

“Thanks for finding GiGi, Daddy.” Boy and dog ran for the truck.

“What’s with the big smile, bro?”

“Nothing, man. I was just remembering an old friend.”

Born in Victoria, Texas in 1974, Edward Jeremiah Monroe was raised in a 19th century farm house (the Hiller House) literally a stone’s throw from the Guadalupe River. Along with his three younger siblings, his companions were various dogs, cats, chickens, rabbits, cows, and the occasional squirrel or other captured/rescued animal. Using writing as a means of rediscovering his early experiences with nature and to explore heavy matters of the heart has led to deep reflection, self-discovery, understanding, healing, and self-forgiveness for Edward, who hopes to one day reunite with his circle of support.

WINNER—CATEGORY: MEMOIR

WINNER—CATEGORY: MEMOIR

War

George K. Johnson

Doing time in the penitentiary is all about perspective. The way we look at different circumstances determines how we act. This means the difference between doing the time, or the time doing you. Personally, I like to make a game of it. If I took the hard road on some of the situations I have encountered, I would not like the person that I would have to become. I prefer to preserve a little humanity in my being. So I find a way to turn any situation into something other than what it is. I do this all of the time in the fields.

Working all day out in the Texas sun is no picnic, let me tell you. The field bosses work us like Hebrew slaves and give us water once an hour, usually. Sometimes we handpick crops, or just clean the weeds out around them. The fallback plan is flatweeding. That means cutting down grass and weeds with our aggies, which is what we call our garden hoes. This grass can grow up to head height and require a considerable amount of effort to cut down. It makes no difference that the prison system has machinery to perform all of these tasks. This is just something they came up with to break the hardheads and to punish the knuckleheads. Hard work and severe weather conditions will make a man get his heart right real quick.

To counteract the negativity, I turn to my imagination. I can daydream with the best of them while performing some menial task that requires more repetition than thought. Take, for instance, when we turn out to harvest the corn.

I like to think of it as going into battle. We travel the turnrows in a string of wagons pulled by a tractor to survey the battlefields. Our opponents stand ready to meet us. It is a wonderful sight. The cornstalks have been planted in straight rows that go on for as far as the eye can see. Their discipline as soldiers is amazing. All of these rows, with each soldier standing perfectly behind another, swaying only slightly as the breeze blows across their ranks.

The tractor stops and the field bosses, our commanders, call us down by squads to prepare for our assault.

“Three hoe, down here on the right,” our commander calls out. He is a skinny little black guy that stands five and a half feet tall and weighs about a buck fifty, but on that horse, with his sidearm, he is the top dog.

“Get your pairs right and your hats off,” he yells. “Ramos, shut the hell up and face forward.” He always has to ride the new guys a little hard. It allows him to assert his authority and lets the inmates, his soldiers, know he is watching them. Plus it gives him a chance to learn the names of the new guys through repetition, so I guess it serves a purpose.

Once two hoe has left, we march forward past the field sergeant, I guess he would be the Sergeant Major, to be counted before we are let loose on the enemy. The lieutenant, our General, watches silently.

“Twenty one, boss Winston. Let them get some green sacks and start them on the other side of two hoe. Take nineteen rows,” he orders.

“Squad it up, three hoe,” our commander yells. “Johnson, Bond, grab some sacks. You two and Smith are strikers.”

We are the squad leaders. That means we will be moving in and out of our squad, tying up full bags of corn and carrying them over to the down row. We also carry the extra sacks and hand them out as needed.

Our commander looks at two other inmates in our squad. “Pritchard, you take the lead. Heller, you’ve got the tail. Count me out nineteen rows.” The last man named takes off and counts the rows. Everyone else falls in on a row in between. We are ready to begin the assault.

“Pick that corn and knock those stalks down. Let’s go,” he roars as he orders us into battle.

The conflict has begun. The cornstalks put up a little resistance, but do not fight back. Their numbers are overwhelming though. We are sweating and breathing hard by the time we get to the end of the row. The only counterattacks are from forces allied with the enemy troops: colonies of ants, swarms of yellow jackets and wasps, and the occasional corn snake. The snakes themselves do not offer much of a threat, but they can get really big and make you think twice before messing with them. Especially if you have a phobia for snakes. Fortunately, I do not and will capture one to scare the crap out of my coworkers. Their reactions are worth the effort.

Our commander rides up behind us on his war mount, occasionally yelling at us to pick up the pace or to talk a little trash to one of the inmates he feels is lolligagging. I make a comment about his horse being deformed—it has two assholes on it. Those who hear the joke, laugh out loud.

“Shut the hell up, Johnson. Get those full sacks on the down row,” he bellows at me.

I just smile at the others and answer, “Yes, boss.” It makes the time fly and offers some respite to our misery.

As the day goes on, so does our battle. Three hoe is called to cease our advance and collect the spoils of war left in the wake of our troops. A short, flatbed trailer is pulled alongside the down rows and we stack the full sacks on it. Once that trailer is loaded, we go to a reefer container to transfer the cargo. Though it has a cooling system, it is not engaged until after the container is full and we are outside. Heaven forbid a little cool air comes our way while we work.

At the end of the day, we are tired, but victorious. The enemy has fallen and we have pillaged his treasure. In our squads, we walk out of the battlefield toward the wagon, our feet dragging from exhaustion.

As we load up the wagons, I take a look back at the war zone. It is definitely not the same. Gone are the perfect rows of soldiers standing and proud in their ranks, reaching for the warmth of the golden sun. What is left is a ravaged landscape littered with the broken remains of our fallen enemy. Egrets serve as carrion birds. Scavengers who scrape a free meal off the land after a battle has been fought. Instead of consuming the “flesh” of our enemy, they scurry around, snapping the crickets and other insects exposed now that the stalks are trampled to the ground.

I feel pity for my enemy. There was never any animosity towards them. I was just following orders. Now they lay fallen and broken, left to rot in the sweltering sun. Eventually, a plow will come to turn up the field, but until then, the fallen soldiers are simply left there without regard. Somehow, I see this as being dishonorable on our part. What we did seems cruel; the act criminal in itself.

My only consolation is that I have stolen some of the ill-gotten bounty for myself. Out of my rubber boots, I pull the four bars of pebble gold I have stashed there. I slowly strip back the green silk covering them, admiring the succulent beauty of the treasure underneath. Juice runs down my chin as my teeth rip the nuggets from their settings. Okay, this battle was worth the effort. This stuff is just plain delicious.

My brothers-at-arms share my sentiments as they reveal their own stolen loot, pilfered during our engagement. Ears of corn appear from inside of shirts, back pockets, out of the tops of socks, and from inside folded hats. Corn silk goes flying in the summer breeze as they strip their treasure. The collective “mmmm” reflects the delight of every man aboard. We joke and talk about what we might do tomorrow. This day is over and it was not so bad because we chose not to let it be that way.

This all could go the other way. I could be miserable and catch an attitude, but what purpose would it serve? Hell, the people who run the prison system would prefer that I be miserable while serving my time. But I decided long ago not to give them the satisfaction. So I treat all of this as a game, every aspect of it. Sometimes I win, sometimes I lose, but one thing remains constant—I am doing it my way!

George K. Johnson has been incarcerated for 25 years. During this time, he has earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology from Sam Houston State University and Masters Degrees in both Humanities and Literature from University of Houston Clear Lake. His preferred genres are fantasy fiction and gothic fiction, though writing about prison life allows him to put his emotional experience in a positive light. Sometimes, it allows him to take a jab at the system as well. George is currently rewriting a fantasy novel originally rewritten for the benefit of his two sons, who are characters in the book.

WINNER—CATEGORY: MEMOIR

WINNER—CATEGORY: MEMOIR

Support

Ryan Forbes

TELL ME ABOUT RYAN.

MOM: When he was in middle school, I told him that when I was his age we were lucky to get two of the three channels available on TV. He said, “Mom, stop using such antiquated analogies.

SHANNON: He’s my hero. He has saved me so many times and. . . I don’t know how he does it.

CASEY: He’s a Pokemon.

FIRST BOSS: He’s my hero. He once had a threesome with two island honeys.

ANDREA: He will do something incredible one day. I hope I get to see it.

TY: He’s a hateful person. I pray for him every day that he gets help, especially in his situation.

CJ: He’s. . . white?

WHEN DID YOU MEET RYAN?

MOM: I am his biological mother, no matter what he says or thinks.

ANDREA: At a concert in Aspen. He silently stood by himself. [Laughs.] Typical Ryan. I came up to him and told him, “Smile, you’ll live longer.”

BRAD: My first day up at college. His parents brought their giant dog everywhere, even the bathroom of the dorm. The dog was so big, it could drink from the sink!

STEPH: One of the Tuesday night happy hours at the Shops.

TY: CeDAR [Colorado Dependency and Addiction Rehabilitation Center].

WHAT IS RYAN’S DEFINING TRAIT?

ANDREA: To me, he’s a romantic. I told him he should write a book teaching men about romance.

SHANNON: I guess “putting-up-with-shittiness.” If that is a trait.

JOE: He’s the most laid back guy I have ever met.

CASEY: God hating him.

TY: [Laughs.] Unforgivable actions and words.

CJ: He’s. . . uh. . . bald?

TELL ME ABOUT YOUR FAVORITE “RYAN MOMENT.”

BRAD: When he did stand up comedy. He told this joke about asking a girl if she had “ever made out on a couch before.” [Laughs.]

CASEY: The Pipe Bomb. . . Like the grenade a soldier has to jump on to protect the team, only she was a pipe bomb. Pokemon had a party at his condo and was “that guy” that night. So he decides to dance the Pipe Bomb. He can barely milk and she is so big, he can’t wrap his arms around her. Then she leaves and Pokemon chases after her, tripping on the steps, and falling on his face. Fuckin’ Pokemon. [Looks down and laughs sadly.]

ANDREA: In California, at our brunch just before our wedding. He went around introducing himself to all of my friends and family. He smiled and laughed with everyone. It was one of my happiest moments just sitting and watching him. [Cries.]

LISA: Probably the lunch we had when we first met in person. He was completely honest and didn’t make any excuses. At first I wanted to leave when he told me what he did, but he was just so. . . accountable.

DAD: During his bar-mitzvah party. The party was at Rice Stadium. I went down to throw footballs with the kids out on the field. We had spent so much time putting everything together for that party. It was so great seeing the kids have fun.

TY: I have no favorite moment. All moments have been tainted by what he did.

WHO IS RYAN’S BEST FRIEND?

SHANNON: Brad.

BRAD: CJ or Ronnie.

CASEY: CJ.

MILO: CJ.

CJ: Ronnie.

RONNIE: [Laughs.] We were best friends. I wanted him to be my maid of honor and to sing at my funeral. Then he got upset about something and stopped talking to me. He is such a girl.

ANDREA: Well, it was supposed to be me, but I don’t know if I ever really was.

WHAT DID YOU AND RYAN DO TOGETHER?

STEPH: Hung out at a couple of happy hours and went on a date at a haunted house. . . that he said he would pay for.

NICK: Played video games, went to the comic book store, and ate Chinese food.

BRAD: He liked to play Smash Brothers. Usually, we would play Bond. Back in the day we played Beer Pong, P-n-A, and King’s Cup. We also hiked the M, camped, and floated the Madison a lot.

CASEY: Drank and talked shit to each other.

JEN: Watched TV and movies. I “made” him watch girly movies, even though I know he secretly loved them. And we hung out with the boys.

SHANNON: When I worked late nights at the Lewis and Clarke Motel, he would come over and protect me from drunks stumbling in from the bars. I remember one time a particularly creepy homeless guy stopped flirting with me and started putting his arm around Ryan. [Laughs.] Definitely my hero.

FIRST BOSS: I would make him tell me his incredible stories! Like the one where the SWAT team surrounded his apartment because of his answering machine message. Or we would go find a karaoke bar so he could repeat his Billy Ocean success and serenade some honeys. Or we would have contests like the one where he chugged three beers faster than I could shotgun three beers. The man is a god!

ANDREA: He would take me and Oriah everywhere. We traveled across the country together, we stayed in the fanciest hotels, and he was always up for anything. If I came home and said I wanted to do something new, he wanted to do it with me. And we had a great time together. He even discovered adventures for us. When he found out about this movie theater that serves dinner and has leather recliner seats in Vail, he immediately made a special movie night for all three of us. It became one of our favorite places. He also took Oriah skiing and tried to look out for her. . . even if he took the stepdad role a little too seriously.

LISA: We talked. Sometimes that meant me just rambling something off at him. We ate at every vegan cafe in Denver we could find. We went to comedy shows, glow-in-the-dark yoga, and he helped me put together a blog for my writing.

CJ: We would just randomly go places. Usually get lost a lot. We also went to a bunch of strip clubs when I broke up with Ronnie.

MOM: One time Ryan was out with his father skiing and he. . . [Laughs] fell asleep. . . while skiing. [Laughs.]

WHY DON’T YOU CALL HIM “RYAN”?

CASEY: The first time I met the guy in college, four of us go for a drive to watch a forest fire. Then, we all come back to my dorm room and Corey and I order a pizza. This guy eats half of it—without paying. So later, Corey and I are walking around talking about this guy who ate half our pizza. How he’s some middle-aged bald guy posing as a college student mooching as much pizza as he can. He’s bald and fat and hungry.

“Like some sort of Pokemon,” Corey says.

And I am like, “Yes! He’s a fucking Pokemon!”

So we decide to call this fuckin’ guy Pokemon because he’s such a fucking Pokemon! Then he turns out to be the nicest dude ever and younger than all of us.

BRAD: Because he likes playing Pokemon. At least that’s why I call him Pokemon.

NICK: Because one day I saw a friend of his call him Furby. It was great. The name fits. So I decided to popularize the name. His friends, other [high school] students who did not know him, teachers, and even his parents called him Furby. It stands as one of my greatest achievements.

ASHLEY: He never told me his name was not Mike.

MOM: The doctors told us Ryan was supposed to be a girl. So we had a whole other name picked out and everything pink waiting for him. I was in labor with him for over twenty-four hours. I tried to have him on his grandfather’s birthday. He just wouldn’t come out until 12:01 AM the next day. When he came out, I asked if it was a boy or a girl, and the doctor said, “It’s a redhead.”

WHEN DID YOU LAST SEE RYAN?

CJ: Ummm. . .

MOM: In August, his sister flew out here [Colorado] from North Carolina and his father drove all three of us down [to Texas] for his carpentry class graduation. His father would not even have dinner with us. He just showed up at the house at 2:30 in the morning yelling at me that it was time to leave.

ANDREA: [Cries.]

NICK: At a cafe in Niwot, right after the accident. I didn’t even know what happened until months later.

BRAD: He visited just before he went to prison. We got the Fifth Floor Roskie gang together for a weekend and played some laser tag. Then he stayed with me and Karla for the rest of the week, mainly just hanging out with us and the kids.

LISA: The sentencing hearing. He was a mess, I mean. . . obviously. They took away his freedom, family, and friends for ten years. He was devastated and scared.

CJ: . . . Like . . . umm . . .

STEPH: A few years ago. . . I think. . . at Scruffy Duffies bar in the shops. Though someone else that might caught my attention. . .

TELL ME ABOUT THE ACCIDENT.

TY: He got drunk, got behind the wheel, and murdered someone.

BRAD: Well. . . he said he was out drinking, walked home, got into his car while he was blacked out, and drove into another car. I guess his car caught fire and the police found him a ways from the crash site. The other guy died.

DAD: The bars over-served him, then kicked him out! They are completely liable!

MOM: He had just started taking anti-depressants and they must have interacted with his epilepsy medication, causing him to black out. The lawyer never brought it up at the trial!

ANDREA: He had just moved to Dallas. He went out. . . and drank. He did not drive to or from the bars. At his apartment, I know he didn’t take his epilepsy medication. That medication. . . during our marriage he would take it and he would be dead to the world. Then sometimes he would . . . do . . . things while he was still asleep. [Cries.] They found him barefoot in his pajamas . . . The lawyer didn’t bring up any of this! [Slams fist.]

STEPH: What accident?

HOW DID RYAN REACT?

MOM: The treatment facility clearly violated HIPAA.

DAD: [Sighs.] He reacted like nothing was wrong. He wanted to hang out with his friend and go to his cousin’s wedding. The lawyer recommended rehab and we found one that could run brain scans to find proof that his epilepsy caused the accident. Instead, they brainwashed Ryan and he joined their cult of addiction. Ryan wouldn’t let us speak to the lawyer anymore. He refused my advice about bringing up epilepsy and the bar over-serving him. The lawyer let Ryan plead guilty without a trial. His uncle helped him make that ridiculous movie in his defense. And Ryan got a tattoo.

LISA: Just totally accountable. He never made any excuses about the accident. He took total responsibility for his actions and his drinking. He talked to other addicts about the accident and answered questions they had. Even though I don’t think he needed the AA meetings, he went all the time. Look, my mom was killed by a drunk driver when I was two years old. If Ryan had not been so accountable, I would not talk to him. I would not hang out with him. And I would definitely not have testified at his sentencing hearing.

ANDREA: He stopped drinking, made a whole bunch of friends, and spent some time with me and Oriah. He. . . was so calm. Even Oriah noticed. Oriah just got her driver’s permit then. She drove Ryan to the store, and from then on wanted Ryan to be the one to accompany her on drives. She told us how much more relaxed he was than me. I don’t think he full knew what was ahead of him. How could he?

TY: No one can recover so perfectly! He was hiding something.

WHEN DID RYAN HURT YOU THE MOST?

CASEY: That night at the Circle Inn when he left with my dead friend’s widow. That was back in the day and water under the bridge.

ANDREA: Leaving me the last time. He moved to Denver for a new job while we were separated. He had told his family we were divorced. I couldn’t believe it. I was just. . . so mad.

DAD: When I found out about the accident. His [younger] sister is the same age as the victim. I can imagine how heartbroken I would be if I lost her.

MOM: The accident completely devastated Ryan’s father. He couldn’t sleep for months.

TY: When he told me that he hoped that I relapsed while I was at CeDAR instead of after I left treatment. Who would do that? Relapsing is the worst thing you could wish upon someone. That was completely unforgivable.

CJ: Like. . . physically?

HOW IS RYAN HANDLING PRISON?

SHANNON: His letters are always so upbeat, I don’t know how he does it. He probably does more in there than I do out here.

BRAD: He seems to be doing pretty good. It’s funny, we used to talk about computer stuff and now we talk about building stuff.

ANDREA: [Laughs.] He knows how to use tools now. I can’t believe it. He sounds so positive in his letters. I know he will do something great.

WHAT DO YOU EXPECT RYAN TO DO WHEN HE GETS OUT?

MOM: He will come back here and take care of me. You see I suffer from Crohn’s disease and Ealers-Donlose Syndrome. Let me show you my leg. . .

ANDREA: He says he will not work with computers again, but he is too much of a geek. He loves computers too much. He will probably make a website that helps people who went through incidents like his.

LISA: Definitely go on a vacation and enjoy his freedom a bit. Maybe after that be a public speaker, telling his story.

DAD: I guess we’ll see who hires him.

BRAD: He says he just wants to start to family.

YOU’VE BEEN QUIET, WHAT DO YOU THINK?

SISTER: . . . I mean he’s my brother. My brother is . . . my brother. I don’t really know how to describe him. I guess no matter how many questions you ask or who you talk to, it’s not the same as meeting him.

CJ: What’s up with all the Ryan questions?

Ryan Forbes is an award-winning author, a (former) professional computer scientist, solar-powered, a lifelong skier, a wannabe husband, an erstwhile step-dad, a phoenix, part dog, the best or worst karaoke performance you will ever witness, up for a challenge as long as it’s not past his bed time, one of millions of modern day American slaves, a pacifist in a war zone, a feminist in

training, a Sagittarius, as well as a man of many hats and one red beard. Ryan is many things. Just don’t call him a Texan.

Lydia Davis, who served as our inaugural Insider Prize judge, is the author of one novel and seven story collections, most recently, Can’t and Won’t (2014). Her collection Varieties of Disturbance: Stories was a finalist for the 2007 National Book Award. She is the recipient of a MacArthur fellowship, the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Award of Merit Medal, and was named a Chevalier of the Order of the Arts and Letters by the French government for her fiction and her translations of modern writers, including Maurice Blanchot, Michel Leiris, and Marcel Proust. Davis is the winner of the 2013 Man Booker International Prize.

Emily and Maurice Chammah are assistant editors at American Short Fiction and directors of the Insider Prize. Emily is the winner of the PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers, and her fiction can be found in The Common. Maurice is a staff writer at The Marshall Project, where he reports on the U.S. criminal justice system.

Deb Olin Unferth is the author of four books, most recently the story collection Wait Till You See Me Dance. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The Paris Review, Granta, Vice, Tin House, the New York Times, and McSweeney’s. An associate professor at the University of Texas in Austin, she also runs a creative writing program at the John B. Connally Unit, a penitentiary in southern Texas.