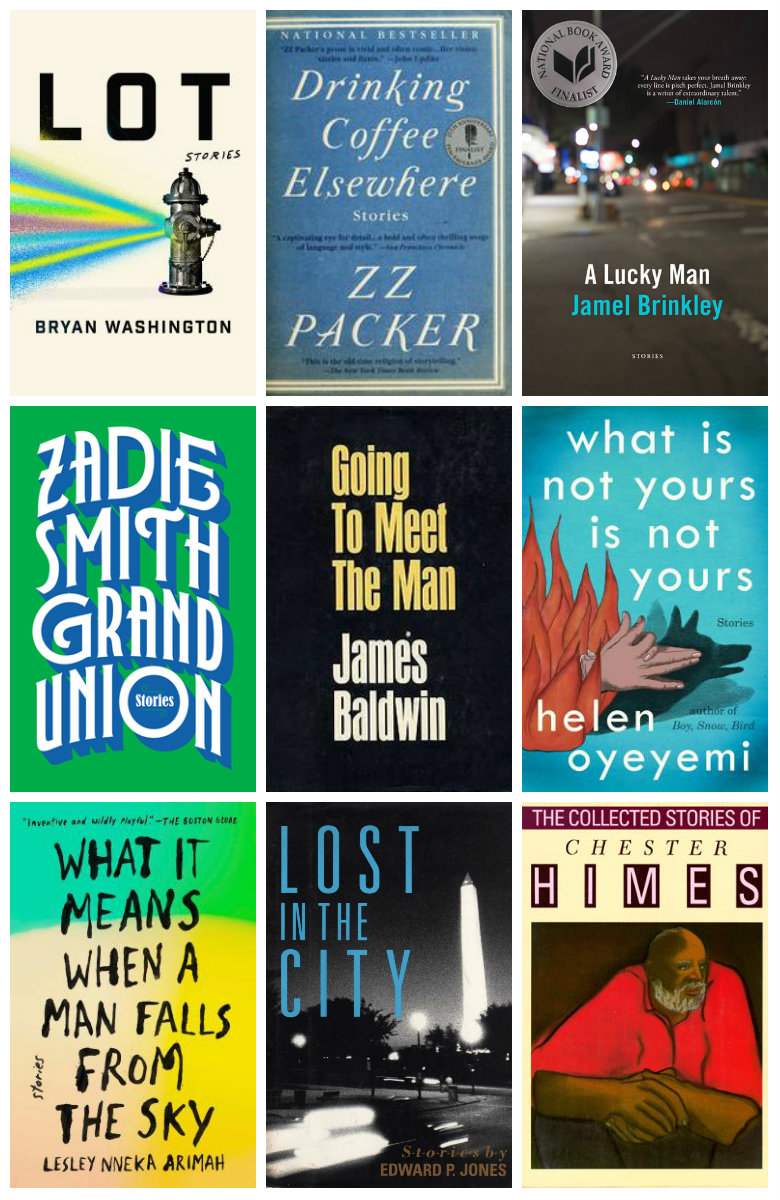

As Black History Month 2020 nears an end, we asked members of our staff compile a list of their favorite short fiction by Black writers. For this list, our scope was broad. After all, while Black History Month has its roots in American history, it’s not an exclusively American endeavor. Canada celebrates along with us during February, but in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the Netherlands, Black History Month is aligned with the start of the school year in October.

As Black History Month 2020 nears an end, we asked members of our staff compile a list of their favorite short fiction by Black writers. For this list, our scope was broad. After all, while Black History Month has its roots in American history, it’s not an exclusively American endeavor. Canada celebrates along with us during February, but in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the Netherlands, Black History Month is aligned with the start of the school year in October.

So, rather than give our staff arbitrary criteria about who should be included on the list and who should not (should the list be limited to living writers? Writers who are American citizens?) we simply asked them about the stories by Black writers they love the most, the stories that they haven’t been able to forget or stories that they’ve found themselves returning to time and again. The results of these questions are broad: from naturalism to fabulism and lush, metaphorically rich sentences to pared down prose, the stories included here are formally and stylistically varied, and their concerns are many. From Baldwin’s classic tale of brotherly reconciliation in postwar Harlem to the genre-busting, multiple award-winning tales found in Lesley Nneka Arimah’s debut collection (she’s appears on this list twice), we hope you love these short stories just as much as we do, and that you’ll take the opportunity to revisit some old favorites listed here (where possible, we’ve included links to the work online so that you can read the stories, too).

—

“Recitatif” by Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison’s first published short story explores the relationship between two girls of different races, Twyla and Roberta, who meet at the fictional St. Bonaventure Orphanage in New York City. The interesting twist of the story is that Morrison refuses to disclose the race of Twyla and Roberta in an effort to challenge readers’ assumptions about racial identity and racial codes. This experiment with narrative ambiguity confronts biases and prejudices that reappear throughout the story in order to envision a future where stories can transcend racial division.

— Patricia Ruiz-Rivera

“Sonny’s Blues” by James Baldwin

There are a few lines in James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” that summarize exactly what it is I love about the art that moves me. Set in 1950s Harlem, the narrator reunites with his estranged younger brother Sonny, a recovering addict, and in an attempt to reconnect with him, he goes to see Sonny play jazz for the first time. During Sonny’s set, he observes one of the older musicians in the quartet and says, “Creole began to tell us what the blues were all about. They were not about anything very new. He and his boys up there were keeping it new, at the risk of ruin, destruction, madness, and death, in order to find new ways to make us listen.” In this luminous story, Baldwin does exactly that. Through language, masterful shifts in time, deep swells of interiority, rhythms and repetitions, Baldwin invites us into a conversation about brotherhood, fear, the dangerous weight of history, the hills of addiction, and the promises we make to those we love and the ones we keep in one of the most masterful and groundbreaking stories ever written.

— Adeena Reitberger

“‘Sorry’ Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea” by Helen Oyeyemi

If you have ever read any of Helen Oyeyemi’s fiction, you know she lets the strange, tilted worlds she builds unspool where they may, so that just when you think a story is about one thing, it becomes another. I think “‘Sorry’ Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea,” from her collection What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, is a wry, layered exploration of what it means to be admired. The narrative sweeps from character to character (including a woman who finds self-love in a teacup) before settling on a teenage girl, Aisha, as she reckons with the perhaps unforgivable misdeeds of a musician she idolizes.

— Michelle Raji

“Brownies” by ZZ Packer

The first story in ZZ Packer’s Drinking Coffee Elsewhere is as surprising and moving as any short story as I know. Set at the fictional Camp Crescendo, the story follows Laurel and her all-black Brownie troop as she navigates a terrible and awkward run in with the all-white Troop 909. For as funny as the story often is, it’s also a serious meditation on the nature of friendship, trust, manipulation, and divisions that seem unbridgeable. This story is the starting gun of a collection in which no story stumbles, but because “Brownies” was the first of Packer’s stories that I read, it’s got a special place in my heart and memory.

— Nate Brown

“Why I Like Country Music” by James Alan McPherson

James Alan McPherson made history with his second collection of short stories, Elbow Room, by becoming the first African-American writer to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. “Why I Like Country Music” is the first story in the collection and presents a playful yet poignant reflection on regional differences in black culture. A beautiful piece that features a Maypole, fancy boots, and young love, like all of McPherson’s masterpieces, this story is humane, intelligent, and deeply nuanced.

— Adam Soto

“The Era” by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

From Adjei-Brenyah’s 2018 collection Friday Black (and anthologized in Best American Short Stories 2019), “The Era” is set in a dystopia that’s far enough away to be comical and close enough to be terrifying. In “The Era,” children have been optimized for objectivity, and “truth” reigns over emotion. Ben, the protagonist, is an outlier in his family and school because he still feels deeply. A masterclass in voice and world-building, “The Era” holds a mirror up to modern societal values while pointing directly to one that’s missing: empathy. This story is electric (and really fun to teach to high schoolers).

— Anabel Graff

“Boys Go to Jupiter” by Danielle Evans

In this story (which was included in Best American Short Stories 2018), a young white woman unthinkingly dons a Confederate flag bikini in a photograph that goes viral on her college campus. What comes next is an astonishingly spot-on parable of our current era: the harm caused by ignorance, by a loss of context and openness, and the mechanisms of shame and doubling down. Claire’s choices frustrate us at every turn, but Evans makes room for her broken heart. This doesn’t absolve Claire, or us—instead the story seems to ask: What will you do with this new information, with this choice? And the next one? Evans manages to achieve all that and a pitch-perfect note of farce suited to this moment in America.

— Erin McReynolds

“Marijuana and a Pistol” by Chester Himes

This 2,000-word Esquire story from 1940 concerns a mind too far gone after a few puffs to recognize its own thoughts, its own body, and the world around it. With memory cut away from a wretched present, apocalyptic fantasies and a .38 revolver lead a man out of his apartment into the streets in search of a catastrophe he won’t have the wherewithal to call his own. In short, hydroponics avant la lettre.

— Philip Baker

“Bayou” by Bryan Washington

This buddy adventure tale takes place on the outskirts of Houston, where Mix and TeDarus discover a chupacabra next to the bayou, and wrestle with how this magical being might fundamentally change the course of their lives. With prose that is fresh, fun, and alive, Washington creates an expertly calibrated narrative that highlights the frailty and complexity of friendship.

— Amanda Faraone

“Escape from New York“ by Zadie Smith

The maestro behind White Teeth and NW is also a killer short story writer. In one of my favorites, Smith asks what happens when you pack three über wealthy friends in a rented Toyota Camry en route to nowhere in the wake of a devastating attack? Zadie Smith spins an NYC urban legend on its head in this darkly hilarious, tragic piece that paints a frighteningly original vision of 9/11. There’s also this great moment of epiphany from the narrator that Smith lands perfectly.

— Uriel Perez

“Girl” by Jamaica Kincaid

Written in the second person, the story “Girl” reads like a list of rules from mother to daughter, most of which are aimed at teaching the daughter how to be a woman. When the daughter’s voice does pop up, it appears in italics, a little boat floating on the overwhelming sea of motherly advice. The story is short and direct, but beneath the practicality is youthful desperation—becoming a woman seems utterly impossible.

— Stephanie Macias Gibson

“Little Faith” by Percival Everett

Set in Wyoming, “Little Faith” follows African American veterinarian Sam Innis on the search for a lost Native American girl. Riding his burly quarter horse across a richly described Western landscape, Innis inhabits a role traditionally slotted for white cowboys, thus subverting worn out stereotypes, yet as he struggles through dehydration and snakebite, he finds himself wrestling with his own assumptions about race and Native American culture.

— Siân Griffiths

“What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky” by Lesley Nneka Arimah

This story drops you into a very real world of climate crisis and racial tension, yet it also weaves in a more dystopian future where Mathematicians have discovered equations for such things as levitation and grief. The protagonist, Nneoma, is one such Mathematician—a grief worker, who draws emotions out of others “like poison from a wound,” and who is confronted by another grief worker overwhelmed by this process of taking on others’ emotions. The whole narrative is as wild and painful as it is sharp and surprising.

— Alexander Lumans

“Sis Becky’s Pickaninny” by Charles. W. Chestnutt

Written at the turn of the last century, this is perhaps the most affecting of the stories in Chestnutt’s Conjure Woman, a collection set in the fictionalized Patesville, North Carolina, in the late 1800s, all of which follow the familiar “Uncle Remus” format of an old African American farm-hand telling an elegant white outsider from the North folksy stories of antebellum plantation days in his heavy patois. But beneath this deceptively conventional format, we see Chestnutt brilliantly navigating the tastes and mores of his day to give a remarkable, subversive, wrenching account of life under slavery, free of the cloying nostalgia of the traditional form, that at once elevates and probes the rich culture he portrays. In this piece, Old Julius tells the story of how a careless plantation owner traded a young slave woman for a horse, sending her off to her new owner without her young child, and the machinations of another slave, with the help of the titular conjure woman, to see her friend safely returned to her son. Chestnutt juxtaposes the various reactions to this tragedy with a quietly damning guilelessness that is the signature force of his collection.

— Rebecca Markovits

“Arizona” by John Edgar Wideman

Framed as a letter to the singer Freddie Jackson, “Arizona” tumbles out as a series of digressions, associations, and memories that circle a central, painful question about the value of art. The effect is profound—like watching a tapestry being endlessly woven and unwoven—as Wideman’s narrator asks Jackson for guidance, or permission, or some kind of certainty in the story he can’t help telling.

— Marta Evans

“Nutcracker” by Tia Clark

There are certain tells you’re reading a Tia Clark story: a brilliant sense of economy, an immediate immersion into (and investment in) character, and, as in “Nutcracker,” a fabulous—and often unsettling—tension that builds just beneath the surface. Clark is adept at tying this tension to the emotional heart of character, and advantaging the world to say something of great meaning. I remember the first time I read “Nutcracker,” and the breath I released after the final line. A truly stunning work of short fiction.

— Peter Kispert

“The Kind of Light that Shines on Texas” by Reginald McKnight

Twelve-year-old Clint must go to a barely desegregated school in Waco, Texas, after his father is sent to Vietnam. While he navigates layer upon layer of racism from both teachers and classmates, Clint also must navigate his opinions about the other two African American students in his class. The story’s language is stunning and the humor sharp, and though I went to public school in Texas two decades later than Clint, the dodgeball descriptions and casual cruelty takes me right back to junior high.

— Stacey Swann

“The First Day” by Edward P. Jones

In this now-classic short story by Edward P. Jones, the narrator, an unnamed five-year-old girl sets out, hand in hand with her mother, to attend her first day of school. What follows is a series of disappointments. First, her mother fails to get her enrolled in Seaton, the school across from their church where she thought she would go and “learn about the whole world.” Then, at the larger school which serves her area, the narrator watches as her mother must ask for help filling out paperwork, admitting that she can’t read or write. A humiliating moment, which the young narrator can’t quite describe. “My mother looks at me, and then looks away,” Jones writes. “I know almost all of her looks, but this one is brand new to me.” This story’s devastation lies in Jones’s masterful rendition of a young, innocent narrator who doesn’t yet understand the cruel dynamics of the adult world around her. Every word of this brief story is poignant and powerful.

— Ashley Whitaker

“Bear Bear Harvest” by Venita Blackburn

“Bear Bear Harvest” is a stylized family drama with a coming-of-age center that slowly reveals speculative and horror flourishes. This story effortlessly takes on so many topics—DNA, race and lineage, community, sustenance, ritual— through the wry and observant voice of an adolescent girl who is the reader’s guide to all of the family business. Every time I read this story, I admire every sharp and energetic line and then brace myself for the ending.

— Melinda Moustakis

“Who Will Greet You At Home” by Lesley Nneka Arimah

We follow a mother-to-be in a place where babies are constructed out of materials at hand—yarn, human hair, etc. A baby becomes flesh as long as the mother is able to protect the child for a full year. Arimah manages to invent a folk mythology that feels both timeless and revelatory, with a prose style full of short, conversational sentences that seduce you into grappling with difficult questions about identity and parenting. I’ve returned to this story many times since it was first published.

— Maurice Chammah

“A Lucky Man” by Jamel Brinkley

The title story of Jamel Brinkley’s stunning debut collection is a deep dive into the beleaguered mind of a middle-aged black security guard at a very white, very wealthy prep school who has become obsessed with surreptitiously photographing the faces of women on the subway with the new smartphone his daughter has bought him—a secret recently discovered by his more successful and preternaturally beautiful wife. We ride along for what we sense to be one more in a long line of quietly embarrassing days in the steadily declining life of a man caught between an unaccountable obsession and a dwindling sense of his own masculinity in the face of a changing world that, in more ways than one, has left him behind. A final humiliation at the hands of a zealous white mother twists the knife in this open wound of a story and brings every illusion about this lucky man’s place in the spaces he occupies crashing down around him.

— Aaron Teel

“Ancient History” by Victor LaValle

From Lavalle’s 1999 collection Slapboxing with Jesus, “Ancient History” drops us into the lives of two high school friends, Horse and Ahab, months after graduation. Horse is getting married to his longtime girlfriend, Melissa, and Ahab has enlisted in the Marines. Told in alternating first-person POV from the perspective of each boy, the story delves into the kind of disdain and love only best friends can feel for one another, as the two protagonists lean into the ways they’ve found to escape their neighborhood—even if it means the possible dissolution of their friendship. No epiphanies. No closure. Just a litany of crisp sentences and moments that, cumulatively, break your friggin’ heart.

— Giuseppe Taurino