Bourbon and Milk is an ongoing series that dives into the perplexing spaces parenting sometimes pushes us and explores the unexpected ways writers may grow in them. If you’re interested in joining the conversation or contributing a Bourbon and Milk post, query Giuseppe Taurino at giuseppe@americanshortfiction.org.

Bourbon and Milk is an ongoing series that dives into the perplexing spaces parenting sometimes pushes us and explores the unexpected ways writers may grow in them. If you’re interested in joining the conversation or contributing a Bourbon and Milk post, query Giuseppe Taurino at giuseppe@americanshortfiction.org.

—

It’s five a.m., and I’m thinking of how my writing life has changed as a dad. A lot. That’s the simple answer. But I can’t help also thinking about the broader ramifications of our proliferation—i.e. its effects on our cats’ lives.

At some point we stopped getting the cats Christmas gifts. Their birthdays were the first to go.

Oh, man. I hear a kid. They’re so crafty. They adjust their schedules to suck up all available time.

For a while, six a.m. was early enough to squeeze in an hour of writing. Then, it was five-thirty, but eventually they caught on to that as well, which is how I got here. If the writing’s going to happen though, there is no other way. I have to fabricate time.

I wrote my first novel with the absolute luxury of time. We lived in downtown Philly. I would wake up at seven, make coffee, sit down at my desk, and write until eleven without interruptions. Around noon I’d walk to Percy Street where the bartender knew my order. I would sit there and think about how great it felt to have exhausted my mental efforts for the day. (At least, I’m fairly confident it went something like that.)

“I wanna do some writing. I wanna write some too. I write some too. I wanna write sumping too pease. I wanna sit in you lap daddy. I sit in you lap? Tytytvvy7vtv767btv76v7v78u. I wanna do it again. I do it one more time. I do it one more time.”

Pre-babies, these morning interruptions would have put me in a foul mood for most of the day, but over the last three years I’ve come to recognize them as something entirely different. I’ve come see them as catalysts for productivity.

*

Being a writer and being a present and conscious parent can very easily come at the expense of one another. Writing is, at best, solitary, and easily selfish a little further along the spectrum. Parenting is, in its very nature, a denial of self for the survival of another. That’s a little dramatic, I suppose, but there’s truth behind that thought. Finding balance has been one of my greatest tests. My writing occurs in the spaces between the conscious moments. Very early in the morning, and during episodes of Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood. My daughter has watched three episodes today. We’ll work through it in counseling. Preserving the thoughts in my head sometimes means “Daddy, where’s the blocks?” will go unanswered until I can get them down on paper.

I’ve been a stay-at-home dad for a while now. It’s the most difficult job I’ve ever had. I will have a cocktail at 2 or 3 today, depending on how the day goes. We potty-trained my daughter with potty treats. Why shouldn’t I get a treat for making it through lunchtime?

All that said, this is the most productive I’ve ever been as a writer. I squeeze four hours into one. I turn off my cell phone. I exhibit self-control. I’m not sure I knew what that was until someone else needed me.

I attempted to put my six-month-old down for his afternoon nap to work on this paragraph. I’ve gotten up from my seat twice in five minutes. He’s still awake. The last time I went into his room he was lying on his back looking up at me, smiling, teasing! Now he’s kicking his legs like he’s running. He’s running away with the last thought I was clinging to!

*

And the hours fly. A paragraph here, a scratched-out re-phrased thought there. It all adds up. Sometimes seeing the thought with a fresh set of eyes thirty minutes later allows for immediate revision.

My revisions, however, sometimes handicap my ability to devote thoughts to dinner. We have to eat? We didn’t make it to the grocery store. We didn’t make it out of the house today. My youngest is still in his P.J.’s and he’ll more than likely sleep in them tonight. He’ll definitely wear them to the restaurant.

*

“It’s a snake!” And it is. My three-year-old is holding up my pocket notebook so that the table of diners behind her can see her latest drawing.

At one time I would have spent my dinner distracted with observations, some of them snarky. I would have listened to other people’s conversations and periodically pulled out my notebook to my wife’s annoyance. After all, writing and present-living are often paradoxical, and when they’re attempted simultaneously, they can short-circuit one another into something graceless.

The pen and notebook still come to restaurants, but they now double as tools of a different type of distraction. My notebooks are piling up with words and drawings. The drawings are usually a crosshatching of lines, maybe a face with eyes or an animal. Some are dated with my daughter’s age next to them. This makes it a little more difficult to go back and find an exact sentence or idea, but it pushes me to transcribe my writing onto my computer more consistently.

*

I’m flipping through my current dinner notebook and just found a note from a few months back:

“On my third Father’s Day, I looked down into your eyes and saw that there will be a last time that you crawl up into my lap. I listened to you squeal and play with your mom. We laughed at you when you stumbled a bit because your feet are small and you’re top-heavy. You played with a cat toy for most of the morning, then you went down for a nap. I’ll be telling you about your first few months, your likes, your dislikes, and your quirks for the rest of your life. These memories will be burned in deep because they’re for both of us. You will tell your children about you from my recollections.”

My awareness of mortality has become much more present since becoming a father. This is a strange thing to think, as my first novel centered on an octogenarian. But this topic is difficult to escape with so many firsts and lasts occurring in such a short span of time.

Someday there will be a final child’s drawing in my notebook. It will all be fiction again. This prescience drives revelation.

*

“C – this is breaking my heart.”

We’re on an after-dinner bike ride and my wife is referring to the last of the tricycle days.

“Look what’s out tonight!” our three-year-old says. “It’s my shadow!”

She’s so excited. And she should be, it’s a beautiful moment. I’m glad she appreciates what she can.

I used to live in my fiction, exist in it. There are times I’ve fictionalized things I would have been better off enjoying fleetingly, intimately. But there’s no way to fictionalize this. It all unfolds much too quickly, and I wish I could stop it in order to fully appreciate the smallest clippings of time.

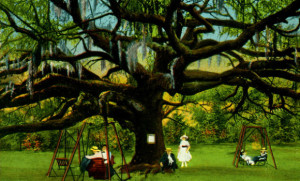

“At the intersection of night and twilight, when my eyes begin to fail because of the gray and blue hues melting into one another, the cicadas speak in unison and the old oaks cast shadows that move because of their swaying Spanish moss. Let it all trickle down in the filter of the trees. The palms diffuse sound and the oaks the light. We play games at twilight. The sky is pale and pink and melts on the water like a rainbow ice cube in god’s bourbon and branch. And that’s where I see my memories. They dance in the trees. At night I turn off the lights in the room and open the windows so that I can enjoy the natural blues and the shadows’ waltz. I kick a cat out of my chair and finish my nightcap in silence.”

The silence is pure fiction.

Christopher Hooks is the author of the novel Henry. He is the Director of Development for Bridge Eight Literary Magazine and a candidate for MFA at The University of Tampa. He lives in Jacksonville with his wife and children where he navigates the obstacles to finishing his next book.