“The mind: a great weapon and an even greater weakness.” – Jace Beleren

It’s 7 A.M. on a Saturday in October 2012. I’m twenty-eight-years-old and yelling “Idiot,” “Fucking terrible,” and “What were you thinking?” into my steering wheel. I’m driving home from Time Warp Comics, where I’ve just lost a Magic tournament. And not just lost, but lost lost: eighteenth out of twenty-five at the midnight release for the newest set, Return to Ravnica. My opponents? Mostly kids who weren’t even born when I was opening three-dollar packs of 4th Edition on the sidewalk outside AJ’s Card Shop in South Carolina.

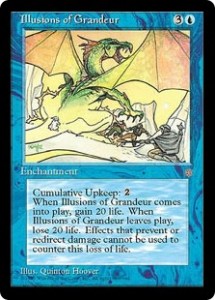

Magic: the Gathering turned twenty years old last August. I bought my first starter deck in the Spring of 1996, sixth grade. Back then, my favorite card was “Illusions of Grandeur.” My love for it was so great, I made it my first ever email account: illusionsofgrandeur@yahoo.com. The card’s art features a small rabbit sitting in the desert while the glimmering form of a dragon surrounds it, scaring off would-be thieves. On its own, it’s a pretty terrible card. But its sizeable effect (“gain 20 life”!) was impressive to teenage-me; now I understand why. That card embodied how I’d tried to survive middle school. I wanted to be cool, attractive, confident. In reality I always felt like that timid thing hidden inside the weak illusion. Yet, I’d hold that card and think: here is my ticket to winning. Less than eight hours ago, headed to the Return to Ravnica Release, I felt like I was the looming dragon; now the veil is pulled away and I am that rabbit again, paws on the wheel, shouting self-deprecating rabbity things.

For those unfamiliar with Magic, here’s an inadequate primer. You’re a wizard. You collect cards that represent your spells, like summoning a “Spiny Starfish” or calling down a “Lightning Bolt.” You and your deck of cards then play other wizards and their decks. The goal is to reduce the other wizard’s lifepoints to zero (starting from twenty) before they reduce yours. Back in middle school, my first decent deck was my “Dragon Deck.” It had great cards, some even worth money. But up against lesser decks (played by better wizards), I lost far more often than I won. It took me years to figure out what mattered was not having good cards, but rather being a smart player. Still, the game operates on a simple enough principle: get good cards, become good wizard; get great cards, become great wizard; beat other wizards, become greatest wizard, win admiration of everyone in middle school, lose V-card beneath the football bleachers, get invited onto Shark Week, be given a chess set carved out of meteorites.

It’s a game that will always have winners and losers.

At the Return to Ravnica Release, plenty of my adolescent opponents handed me 0-2 match losses. Most were very nice about it. Some were slightly condescending without realizing it. And a few, at thirteen-years-old, were already very self-aware dicks, which made losing to them all the worse. These young guys play every weekend (if not every day), the same way I did when I was their age. Later, in college, I would drive up from Charleston to meet all my old Magic-playing friends in Columbia. From there, we’d drive to Charlotte or Durham or Greenville for large tournaments in school gymnasiums. Before the first round, my friends and I would huddle up in the style of high school football teams. Together, as Team Sluggler, with our hands held in the middle, we’d shout in unison: “The only lifepoint that matters is the last!”

Admittedly, writing about failure feels as if it’s built to fail. How to explain your feelings of incompetence without your words coming across as a pitiful, melodramatic soliloquy? Everyone experiences failure, daily and in extremis—what more is there to illuminate about the subject, especially when talking about a card game with spell names like “Goblin Ski Patrol,” “Skithiryx, the Blight Dragon,” and “Jar of Eyeballs”?

In a Lifehacker article from 2011, “Why Comparing Your Level of Productivity to Someone Else’s is a Fool’s Errand,” Adam Dachis explains that you only see someone else’s productivity (not their break time or their struggles); yet, you compare your own total existence—an unbalanced comparison—dooming yourself to always come up short. The article invokes a Theodore Roosevelt quote: “Comparison is the thief of joy.” In Magic, the fundamental action is comparison: Am I a greater wizard than you? Have I collected better cards? Will I plan the correct moves far enough ahead like in a chess game except with “Gloom Surgeon” and “Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker” for pieces?

The irony is not lost on me that Magic’s gameplay is essentially a thief’s agenda. You play with the front of deception. You hold a hidden hand. You lure your opponents into false confidence by not aggressively attacking with your “Plague Rats,” or you inspire false caution by keeping Lands in your hand so it looks like you have more spells. In Magic, comparison is not the thief of joy. The thief could be distraction. Or poor foresight. Or lack of discipline. Because at the end of every single Magic game, someone leaves the folding table with zero lifepoints. Before that moment, no matter how soundly your opponent is beating you, there’s always a glimmer of hope that you’ll top-deck the perfect card and become the thief of joy rather than its victim. That glimmer of hope is the reason this kind of failure feels so immediate and personal. Whenever I lose, I always think there’s something I could have done differently. If anything, it’s regret that wears the thief’s cloak.

II. “Delusions of Mediocrity”

In tenth grade, as my collection expanded, I discovered a new favorite card: “Delusions of Mediocrity.” While the card doesn’t have quite the same appeal as “Illusions” (it only adds ten life instead of twenty), it does include a line of flavor text that reads: “When nothing but second best will do.” I adopted that motto. I changed my email: delusionsofmediocrity@hotmail.com. I’d come to treasure the idea of aiming for the middle of the pack, for “second best,” or even “eighteenth best.”

In tenth grade, as my collection expanded, I discovered a new favorite card: “Delusions of Mediocrity.” While the card doesn’t have quite the same appeal as “Illusions” (it only adds ten life instead of twenty), it does include a line of flavor text that reads: “When nothing but second best will do.” I adopted that motto. I changed my email: delusionsofmediocrity@hotmail.com. I’d come to treasure the idea of aiming for the middle of the pack, for “second best,” or even “eighteenth best.”

My first two years of high school, I struggled. Algebra was a foreign language of unknowns. I could memorize German vocabulary but could hardly speak coherent sentences. For the first time ever, I even loathed my English teachers. Getting a C suddenly took on the sheen of great achievement; yet, it still felt like disappointment. I’ve always made the worst out of not doing the absolute best. So these freshmen- and sophomore-year delusions of mediocrity were a welcome reprieve from that perfectionist burden. They made “failure” okay because instead of shooting for the stars, I was just aiming for the fluorescent lights in the ceiling.

Around that same time, Varsity Blues came out. I saw it twice in theaters. Because A) Ali Larter and B) James Van Der Beek as backup quarterback Moxon uses the worst Southern accent to say one of my all-time favorite cinematic lines. When I watch this movie now, a different moment sticks out to me. After head coach Kilmer has been kicked off the team at halftime of the District Championship for choking Moxon, the quarterback gives his climactic inspirational speech: “Before this game started, Kilmer said ‘forty-eight minutes for the next forty-eight years of your life.’ I say ‘fuck that.’ All right? Fuck that. Let’s go out there, and we play the next twenty-four minutes for the next twenty-four minutes, and we leave it all out on the field. We have the rest of our lives to be mediocre, but we have the opportunity to play like gods for the next half of football.” It’s such a weird speech. Is he saying, “We are obviously average people, but when we play this game, we’re not”? Again, mediocrity rears its ugly dragonhead as the preferred end result. Second best will do fine. Eighteenth best will do fine.

But I don’t want to short-shrift failure. It’s not simply Roosevelt’s loss of ecstasy in the face of others’ superiority. It’s not only falling short of what you wish you were. And it’s not just losing a game, football, or Magic. It’s also a James Wright poem:

Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota

Over my head, I see the bronze butterfly,

Asleep on the black trunk,

Blowing like a leaf in green shadow.

Down the ravine behind the empty house,

The cowbells follow one another

Into the distance of the afternoon.

To my right,

In a field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year’s horses

Blaze up into golden stones.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

I’ve written this poem on the first page of all my notebooks. The sharp, sudden blow of its final line never fails to split the length of me: I have wasted my life. I draw both fear and comfort from its disparate conclusion.

When I consider how long I’ve played Magic and yet still struggle with any consistent level of success—let alone mediocrity—I too fear I have wasted seventeen years. I fear they’ve amounted to little more than a vast collection of painted cardboard, thousands of dollars handed over to Wizards of the Coast LLC, and a lingering distrust of my own abilities. That last one is what hollows me out most on the early morning drive home from Time Warp. Shouldn’t I have more to show for my lifelong efforts? Shouldn’t I at least have learned to take failure in stride?

In middle school, when the Magic addiction was so rabid among my peers (I myself had a pack-a-day habit at AJ’s), I developed aspirations. I knew I wasn’t good, but I wanted to be. I didn’t have the best cards or the money to buy them, but I wanted both. All I had was my inchoate “Dragon Deck.” I traded for more cards, play-tested into the weekend predawn, read Inquest and Scrye. I tried not to waste my time. And while in retrospect, that time does not feel wasted—I knew the words “fecundity” and “juggernaut” on the SAT purely because I owned those eponymous Magic cards—it is difficult now, in 2014, to not feel like I hit the ceiling long ago. The failure becomes not only the inability to break through it, but also the realization that I’ve spent so long pressing on its brightly lit yet immovable surface.

In Wright’s 1964 reading at the Guggenheim Museum, he prefaces “Lying in a Hammock” by saying that he wrote it because he had been trying (and failing) to write a review of a bad book; instead of writing the review, he got drunk, woke up hungover, and wrote this poem. Did he waste his life because he got drunk? Or because he was trying to write a review of a bad book? If failure is wasted opportunities, then my feelings are warranted. But if failure is instead spending time doing something you don’t enjoy doing, then my playing Magic (regardless of my loss-to-win ratio) is not a failure at all because I love playing it.

III. “Control Magic”

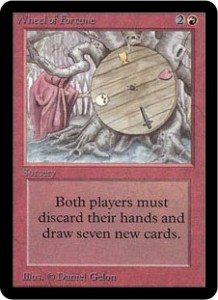

At the end of high school I remember trading for two specific cards. One was called “Wheel of Fortune”—an out of print card, simple by all appearances. But the simplicity belied its strength. You and your opponent each discard your current hand and redraw a new hand of seven cards. It can radically shift a game’s tide, or it can cement a win. The card’s picture (a cloaked figure standing beside a wooden wheel marked with a heart, a skull, a cup, and a dagger) calls to mind the caprice by which I seem to live the majority of my life.

At the end of high school I remember trading for two specific cards. One was called “Wheel of Fortune”—an out of print card, simple by all appearances. But the simplicity belied its strength. You and your opponent each discard your current hand and redraw a new hand of seven cards. It can radically shift a game’s tide, or it can cement a win. The card’s picture (a cloaked figure standing beside a wooden wheel marked with a heart, a skull, a cup, and a dagger) calls to mind the caprice by which I seem to live the majority of my life.

It’s not like I’ve never won a game of Magic (or a tournament). I have. However, I’m far more likely to chalk up these wins to good luck, whereas each of my losses is my own fault, not Fortune’s. It’s a strange double standard rooted in my perfectionism. Success: a gift from the gods. Failure: a paucity of one’s own fortitude.

The other card I traded for was brand new. A rare one called “Worship” from Urza’s Saga. As long as “Worship” was in play and as long as you controlled a creature, your lifepoints could not be reduced below one; it, in effect, made you immortal, immune to mistakes as long as you held onto that one all-important creature. Instead of adding life to your total, “Worship” provided a catchall safety net, and it only required that most significant of lifepoints: the last one.

The other card I traded for was brand new. A rare one called “Worship” from Urza’s Saga. As long as “Worship” was in play and as long as you controlled a creature, your lifepoints could not be reduced below one; it, in effect, made you immortal, immune to mistakes as long as you held onto that one all-important creature. Instead of adding life to your total, “Worship” provided a catchall safety net, and it only required that most significant of lifepoints: the last one.

These cards came into my life at a time when positivity and uncertainty joined forces. In eleventh and twelfth grade, I started getting all As. I was editor for the school’s literary magazine. I had an English teacher who would prove to be one of my most influential mentors. I had my first girlfriend. And I’d gotten better at Magic. Then, come August 2002, I was on the verge of going to college. I would be living away from home for the first time. I would be leaving behind a girlfriend of almost a year and friends of ten years. I would know no one, let alone other Magic players. As often as the “Wheel of Fortune” lands on a heart or a cup brimming over, it also lands on a skull or a dagger pointing toward you. But when things look darkest, it’s helpful to remember moments of victory. And so I worship at their altar.

Ironically, the victory I always return to happened when I was still a fledgling Magic player.

In middle school, I was a member of the Chess Club, run by Mr. Kneece, the Industrial Tech teacher. I’ve always been a slow game player—chess, Magic, pool, HORSE, you name it. I’m cautious, defensive, silent. I think out all my options because I don’t want to make a mistake that will cost me the turn, the game, the match, the tournament, my integrity. Of course, you learn from mistakes. Your failures become your fuel. But it’s the quantifiable nature of Magic and loss (the zero lifepoints) that makes it all the more stinging. Most sports require an accumulation of points to win, not a decimation of others’ (like Cornhole and Curling). Chess is a close kin to Magic. They’re both about tactical attrition. But while you can still win a game of Magic with only one lifepoint, you cannot win a game of chess with only one piece.

Mr. Kneece always hosted an end-of-the-year club tournament. In the last weeks of eighth grade, I started burning my way through the tourney bracket’s opponents. There were some close games against Zander and TC, but I survived because I’d learned from my father to play strong endgames. In the finals, I played my good friend Dug. In addition to being one of the school’s best Magic players, he was also a great chess player. I still beat him.

However, once you won the club bracket, you then had to play Mr. Kneece. That last week of Chess Club, Mr. Kneece and I sat on opposite sides of an apple barrel, the gameboard set between us. Fluorescent bulbs buzzed overhead, sawdust drifted through the air, Mr. Kneece’s sandy moustache twitched every so often. The rest of the club crowded around us. I was more than nervous. I’d never beaten him before.

We both opened standardly, played conservatively, watched for the other one to make a mistake. I favored my Knights and he his Bishops. At some point mid-game, I knew I’d made a wrong move. Mr. Kneece pounced. But in his aggressive attack, he left his back row open. We traded more pieces. We each lost our queens. After hours of playing, with both our sides much reduced, I thought even more carefully about every move. I knew that as long as I held onto my last Knight, I had a chance. I kept telling myself that—until the unthinkable happened: I checkmated Mr. Kneece. I didn’t win anything. No trophy. No money. No invitation onto Shark Week. But shaking his hand after that game has stayed with me as a moment where failure, like Roosevelt’s thief, finally fled the room.

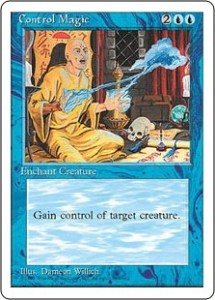

If you’ll permit me one more card (to put it all in perspective, as of right now, there are over 12,000 unique Magic cards), “Control Magic” was given special admiration by anyone and everyone I played. It simply gives you control of an opponent’s creature. Like most of the cards I’ve mentioned, casting it can change a game’s tide quickly and drastically. But what most of us appreciated about it was that it granted you an extra, unexpected, even lucky advantage. Maybe you draw it after casting “Wheel of Fortune,” or maybe it provides the one creature you need to survive with a “Worship” in play. No matter what, you’re given a chance to break through your own ceiling because you reach beyond your own deck’s capacity to win. I’m not claiming to know what metaphor “Control Magic” stands for in the real world. I don’t think there is an equivalent. Maybe prayer, maybe law of averages, maybe wishful thinking. What I do know is that every so often, you end up winning. Your illusions become reality. You beat the Industrial Tech teacher at his own game. You take control.

If you’ll permit me one more card (to put it all in perspective, as of right now, there are over 12,000 unique Magic cards), “Control Magic” was given special admiration by anyone and everyone I played. It simply gives you control of an opponent’s creature. Like most of the cards I’ve mentioned, casting it can change a game’s tide quickly and drastically. But what most of us appreciated about it was that it granted you an extra, unexpected, even lucky advantage. Maybe you draw it after casting “Wheel of Fortune,” or maybe it provides the one creature you need to survive with a “Worship” in play. No matter what, you’re given a chance to break through your own ceiling because you reach beyond your own deck’s capacity to win. I’m not claiming to know what metaphor “Control Magic” stands for in the real world. I don’t think there is an equivalent. Maybe prayer, maybe law of averages, maybe wishful thinking. What I do know is that every so often, you end up winning. Your illusions become reality. You beat the Industrial Tech teacher at his own game. You take control.

This kind of success simply doesn’t happen as often as you’d like; enter stage right, Failure.

Another Wright poem, “As I Step Over a Puddle at the End of Winter,” comes to mind when I think back on all this failure (and the exceptions). Its epigraph comes from a Chinese governor named Po Chu-i: “And how can I, born in evil days and fresh from failure, ask a kindness of Fate?” Maybe that’s what I’m doing on the tortured A.M. drive home: asking for a kindness from Fate while I lament not meeting my own expectations. Next time put me in second place, Fate. Don’t mana-screw me in a tiebreaker match, Providence. Grant me control when I need it most, Fortune; or better yet, a “Control Magic.” Do not stack one more failure onto the slagheap of failures because it is one more step away from perfection, which is impossible, but which nevertheless has both a price I’m willing to pay (regret + twenty-four-dollar entry fee) and a prize I’m willing to aim for (one booster pack + playing the game itself). O Fate, O Fortuna, O Serra Angel, O Bunny Inside the Dragon, I would gladly waste my life as Wright had in that hammock so that I could win once again and not waste my lifepoints.

Alexander Lumans is currently the Spring 2014 Philip Roth Resident at Bucknell University. He has been awarded fellowships/scholarships to the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, Blue Mountain Center, ART342, Norton Island, RopeWalk, Bread Loaf, and Sewanee. He received the 2013 Gulf Coast Fiction Prize, 3rd place in the 2012 Story Quarterly Fiction Contest, and the 2011 Barry Hannah Fiction Prize from The Yalobusha Review.His fiction has appeared in Black Warrior Review, Blackbird, Cincinnati Review, The Normal School, and Surreal South 2013, among others. He is co-editor of the anthology Apocalypse Now: Poems and Prose from the End of Days (Upper Rubber Boot Books). He graduated from the M.F.A. Fiction Program at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. And you can find him on Twitter @OldManLumans.