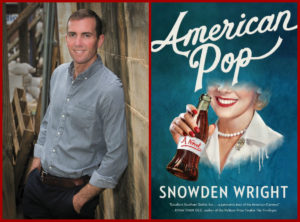

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene from American Pop, the new novel by Atlanta-based author Snowden Wright. Published by Harper Collins earlier this week, the novel follows the Forster family, a clan whose fortune is made via patriarch Harold’s famous Panola Cola Company. With their roots planted in the fertile soil of America’s Gilded Age, the Foresters’ story seems, at first, like the tale of a charmed (and charming) tycoon but soon presents as something else entirely. An impressively resonant work of historical fiction, American Pop examines the particularly volatile mixture that seems to be at at the heart of all of America’s legendary families: charisma, fortune, fame, and their unfortunate obverses.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene from American Pop, the new novel by Atlanta-based author Snowden Wright. Published by Harper Collins earlier this week, the novel follows the Forster family, a clan whose fortune is made via patriarch Harold’s famous Panola Cola Company. With their roots planted in the fertile soil of America’s Gilded Age, the Foresters’ story seems, at first, like the tale of a charmed (and charming) tycoon but soon presents as something else entirely. An impressively resonant work of historical fiction, American Pop examines the particularly volatile mixture that seems to be at at the heart of all of America’s legendary families: charisma, fortune, fame, and their unfortunate obverses.

—

American Pop is told in a nonlinear chronology—inspired by the structure of Edward P. Jones’s amazing novel, The Known World—with chapters that jump between timeframes, perspectives, and locations. As such, I could have started the novel almost anywhere, so long as the opening chapter introduced the novel’s essential setting (a soft-drink company) and the characters (the family that owns it) and, most importantly, made readers want to know more about both.

In this outtake, I tried to introduce the Panola Cola Company and the Forster family from the perspective of an outsider, someone new to each. I figured that way he would serve as a stand-in for the readers. Ultimately, however, I decided such a method was misleading. This is not the story of a reporter working on a piece about a soft-drink company and the family that owns it. This is the story of that company. This is the story of that family.

— Snowden Wright

—

1.1

The PanCola Summit—Based Out of Tuscaloosa—The Church of Pan, the Cult of Pan—A Dinner Invitation—Montgomery, Harold, Ramsey, Lance—Imminent Complications

Years later, Clifford Dawson’s obituary would describe him as the foremost expert on the history of The Panola Cola Company, but on June 25, 1911, he was only one of hundreds of nameless salesmen in shirtsleeves waiting to register for the PanCola Summit in an open field near Batesville, Mississippi. The company referred to them as Panhandlers. Called “drummers” in other industries because they drummed up trade, Panhandlers were salesmen who, indoctrinated by the “PanCola Bible” on company policies, traveled the railways across the nation, passing out coupons for free samples, overseeing advertisements, contracting soda-fountain proprietors, and, according to the bible, “routing any venue that dares sell imitation or adulterated PanCola.” That last duty worried Clifford. With such aggressive diction, obvious territorialism, and hints of potential violence: Who knew what a company like that was capable of doing? He kept repeating the verb “rout” in his mind while gradually, mechanically inching toward the registration table, indistinguishable salesmen in front of and behind him, all of them prepared to rout anyone who got in their way. Clifford’s shirt grew damper with every step he came closer to the table hung with a banner that read, “Welcome to the Inaugural Panola Cola Sales Convention!” On finally reaching the registration table, he was asked by a dark-suited man who did not raise his eyes from the clipboard in front of him, “Name?”

“Peter McGuire,” said Clifford Dawson.

His editor had given him the assignment. Although The Saturday Evening Post did not condone, publicly at least, reporters going undercover, Clifford had made a strong case for the necessity of his doing so, repeating the mantra, “Chefs always cook best for critics.” He wanted to be served a typical meal. A 22-year-old native of Baltimore, Maryland, who’d read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle seven times, Clifford aspired to be a muckraker, and his investigation of the country’s leading soda manufacturer he figured was his chance.

The sleeping quarters for the salesmen, a series of Quonset huts situated near PanCola’s central office, had the feel of army barracks, no furnishings except for rows of bunk beds with tightly tucked sheets. On the walls hung memorabilia from throughout the twenty years since the company had been founded: tin signs, fading one-sheets, banners, calendars, and newspaper advertisements, all of which were scrawled with the company slogan, “The Sweetest Thing Around.” A “Panola Heat Wave” clock on one wall read the time as a hair above thirsty, and a group of cartoon children in a poster dreamt of the “PanCola Tooth Fairy.” In a framed sepia photograph, three grown men, hatted and suspendered and groomed, stood in agrarian gentility before the arcade of a drugstore, Forster Rex-for-All, within the late-afternoon light of a warm southern day. Clifford knew that store to be the birthplace of The Panola Cola Company, where Forster’s Delicious Fizzy, the original iteration of the company’s signature product, was invented in 1890.

“Top free?” Clifford asked a man’s sweat-drenched back. Whoever the back belonged to was rummaging through a suitcase on the bottom bunk.

The man straightened up and turned to look at Clifford. “You bet,” he said, extending his hand for a shake. “Richard Hartwell. Baton Rouge.”

“Peter McGuire. Tuscaloosa.”

“Glad to meet you.”

“Pleasure.”

Over the next few minutes, Clifford, unpacking his suitcase and assessing the quarters, felt increasingly at ease, until the man below him, Richard Hartwell of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, asked a question that struck Clifford like a spur to the base of his spine.

“Where’d you say you were based out of again?”

“Tuscaloosa.”

“Didn’t know we had an office there.”

Clifford had meant to say Chattanooga. Clifford had meant to say Chattanooga. Clifford had meant to say Chattanooga. “It’s new.”

“Damned if there aren’t more sprouting up all the time.”

In his mind, Clifford heard his editor’s last words to him—“All the meticulous planning in the world will be for naught when you’re out there in the field”—as he agreed with this Richard Hartwell, hoping his voice didn’t crack. He picked up the information packet he’d been given on check-in, mentioned he wanted to get to the opening ceremony early, and made his way through the salesmen milling about the quarters.

Inside the information packet he found a copy of the company newsletter, The PanCola Tribune, the lead article for which began, “Did you know that by 1910 the American people were spending more than double on fountain drinks each year than their government was on the Army and Navy?” Aside from that, the newsletter contained pieces on “soda drunkards,” the Malted Milk War of 1889, the “Panola Cola Girl” for June 1911, and guidelines for how best to deal with retailers, including, “Do not refer to Panola Cola as ‘it.’ Our name is our fame.” Clifford was so absorbed by the newsletter he almost ran into a wall. Only after looking up did he realize it wasn’t a wall but rather a crowd so dense it might as well have been.

At least two hundred men were packed into the amphitheater. Grass papier-mâchéd to the ground by the trampling of heavy feet, bowler hats in perpetual fanning motion against faces pinked by the afternoon heat, loosened four-in-hands, sack coats unbuttoned, and casual exchanges kept expressly muted in anticipation of a spectacle, the atmosphere of the PanCola Summit’s opening ceremony reminded Clifford of a sporting event. He witnessed further proof of the comparison when, as a figure walked onto the stage, everyone in the crowd began to whisper what he mistakenly heard as, “Hoping for a score.”

“The first time I saw Houghton Forster in the flesh I could barely see him,” Clifford would later write in his exposé. “He was nothing but a blur on a stage. The only thing I could see clearly was the devotion he inspired in the company he’d founded.”

Houghton’s speech, with its call-and-response aspect, seemed to Clifford evocative of two things, a church revival and a cult meeting, the former if he were being generous, the latter if he were not. “What’s the sweetest thing around?” prompted, “Panola Cola, I’ve found!” “They say we’re a fad,” prompted, “Hell no, we won’t go!” “What’s our name again?” prompted, “Panola Cola! Panola Cola! Huzzah!” At the end of the speech, while hundreds of Panhandlers cheered their leader, Clifford hurried around the perimeter of the crowd, headed for PanCola’s central office, where he hoped to find some privacy.

He found plenty in an immaculate restroom on the ground floor. The restroom featured a high tile wainscot along its walls, nickel-plated fixtures, pedestal sinks of solid porcelain, and, everywhere else, wood paneling as white as the label of the beverage that had paid for it. Clifford checked for feet in the stalls and then went inside one of them himself. While there, he furiously scribbled in his notebook, trying to get it all down, the excitement of the crowd, the best lines of the speech, before he had a chance to forget.

Almost half an hour later, Clifford, his writing hand as numb as his butt, was standing at one of the sinks when a man entered the restroom, paused for a moment, and, rather than go to a stall, began to wash his hands in the sink next to Clifford’s. Specks of water ricocheted off the porcelain. They darted pell-mell through the air, some landing on Clifford’s jacket, right over the pocket where he’d placed his notebook.

“How’d I do?” asked the man.

“Excuse me?”

Clifford, who until that moment had refrained from looking too closely at the man, stared at him in the mirror. In contrast to the overwhelming whiteness of the room, his handsome face nearly glowed with a suntan, tufts of gray at his temples, eyes the color of cornflowers in the spring. During his preparation, Clifford realized, he had only seen the man in black-and-white photographs. Houghton Forster said, “That memorable, huh?”

“No, um, well. I mean to say, uh, it was an excellent speech. Sir.”

While laughing Houghton dried his hands. “It’s okay. I’m a bit immune to it myself, I’ve given it so many times.” He patted Clifford’s shoulder. “Walk me to my car. Let’s talk. I like to hear from my people one-on-one whenever possible.”

Back outside the evening was in its approach. A few dozen salesmen were scattered throughout the lawn in front of the building, all of them obviously waiting to speak with their boss one-on-one, all of them obviously disappointed they had missed their chance. Houghton barely seemed to notice them. Hands in his pockets, he strolled along a line of cape jessamine that marked the perimeter of the parking lot, shadows of pine trees by his feet, stretching longer with each passing second. “Here’s a question for you, friend. How would you improve this company?” he asked Clifford.

“Do my job and do it well?”

“Ha. You’re quick.” Houghton grinned on one side of his face. “But put yourself in my shoes. If you were me, what would you do to improve PanCola?”

Months earlier, after the publication of a particularly scathing article on his administration, President Taft had sent The Saturday Evening Post a letter whose petulant, churlish, infantile tone prompted Clifford’s editor to note, “Should you like to see the true nature of a man, wound his pride and then ponder the expletives.” With that statement in mind, Clifford decided against all the polite answers he could think of, “Keep the bottling rights,” or, “Diversify,” or, “Always protect your brand,” and instead chose one he hoped would reveal the authentic Houghton Forster.

“What will soda inevitably do?” he asked.

“Sorry?”

“Go flat.”

Houghton said, “I’m not sure I follow.”

“Sock your money away. This business won’t last.”

Clifford could have sworn, even though he knew it was only his imagination, those words had an echo. They seemed to bounce off the pine trees in the distance, ping against the building to the rear, pulsate between nearby cars, and slowly come to rest in the quiet air between the two men. Clifford cautiously looked at Houghton.

The grin that had been on one side of his face was now on both. “Just what I wanted to hear. This’s why I like to speak with my people face-to-face. Real honesty!” Toward the darkening sky, Houghton let out a guffaw that scattered the handful of Panhandlers still remaining on the lawn. He asked Clifford, “What’re your plans for dinner?”

“I think the schedule said something about a barbecue over by the quarters.”

“Wrong. You’re eating at my house. Get in.”

Despite Clifford’s protests, Houghton forced him into the passenger seat of his Ford Model T, a more modest vehicle than Clifford would have guessed he’d own. The interior was covered in orange dust. Over the next twenty minutes, the jostling of the car holding steady with the throbbing of his pulse, Clifford stared out the window, its view a picture show of grackle perched in beeches, horses grazing, cows lowing, water turkeys swimming amid water oaks, and lightning bugs that looked to him like holes punched in a stage backdrop. One question nagged Clifford. Why the hell hadn’t Houghton asked his name yet?

“That’s ours up there,” said Houghton, pointing ahead. “The Sweetest Thing.”

A Greek Revival mansion, with a low-pitched gable, fluted columns, and a cedar-shingled roof, the Forster family home, apparently named after the main company slogan, was far less modest than Houghton’s Model T. Clifford figured it had to be fairly new. A corner of the structure was unfinished, a chunk missing, as if a giant had mistaken it for a cake and taken a bite. Inside the house, after they had parked the car in a stable, Clifford encountered, one by one, all of the family members Houghton had been referring to when he’d called The Sweetest Thing “ours.”

The first was a seven-year-old boy. Dressed in short pants and saddle shoes, Harold came running down the double-winder stairs, across the chandeliered foyer, over a Persian carpet, and into his father’s outstretched arms. “Daddy,” he said, “Monty won’t let me play with his cap gun.”

“Heavens no!”

“Tell him to let me play with it.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Who’s him?”

Houghton shifted the weight of his son. He did not look at Clifford as he said, “Him is Clifford Dawson. He’s a reporter for a magazine called The Saturday Evening Post.” He lowered his voice to a whisper, still not looking away from Harold. “Can you do me a favor, Haddy? Take a gander at Mr. Dawson. Is his mouth hanging open? Are his eyes big as a bug’s?”

Without the boy giggling in confirmation, Clifford couldn’t be sure if he would have even known whether he was open-mouthed and bug-eyed, he was in so much shock from what Houghton had just revealed. His cheeks blanched as the seven-year-old stared at him from his father’s arms. “I’m this many,” the boy said, holding up three fingers.

“It’s been a long time since you were that many.” Houghton set his son on the ground. “Run along and tell Momma we’re going to be one more for dinner. Cliff—may I call you Cliff?—let’s get a drink in you. Looks as though you could use it.”

The boy ran in one direction while the two men walked in another. In the study, Houghton stood at a bar cart, filling two glasses with Scotch, then handing both to Clifford, who dispatched them in quick succession. Houghton poured another round but gave only one of the glasses to Clifford.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of, Cliff,” he said, taking a seat in a wingback. “I don’t want to influence your article one bit. I want it to be fair and impartial.”

“But how did you know?”

“Patent medicine.”

“What?”

“Twenty years ago, magazines like yours had a boom that took them from local rags to national publications. Any guess who was responsible for that boom? Patent-medicine makers.” Houghton placed his glass on a coffee table. “There used to be a time when Collier’s was full of ads for Doc Nether’s Miracle Nerve Tonic. Do you know what those miracle nerve tonics are called now? Soda pop. I’ve still got friends in the industry I helped build.”

Clifford finished his drink. “Fair and impartial, you say?”

“Absolutely! I’ll admit, it may have irked me they thought they could send—”

A boy stood in the doorway to the study, only a few years older than his brother but with a bearing, Clifford noticed, of a child who people describe as having an old soul rather than call him “rightfully suspicious of adults.” His hand clung to the doorknob. In response to his father’s question of what he needed, Montgomery said, “Mother asked me to tell you it’s time for dinner.”

“Did you gather up those sticks in the backyard?”

“I piled them in the wagon.”

“Good boy.” Houghton motioned for his son to come closer. Although he was obviously reluctant to enter the room—either that, thought Clifford, or he really liked the doorknob—Montgomery walked to the other side of the study, where his father tousled his hair and told him to go wash up for dinner.

“Was Houghton Forster a good parent? He certainly seemed so at the time,” Clifford would later say in an interview. “But look at what eventually happened to his children. That much tragedy couldn’t just be a result of incredibly bad luck.”

In the dining room, a candle-lit mahogany table centered within the dark-walled space, Clifford met the remaining three residents of The Sweetest Thing, though only one, Annabelle, was present at the time. She did not yet know the child she was pregnant with was actually twins.

“Mr. Dawson, the notorious reporter, I presume,” she said, offering her hand.

The notorious reporter took it. “Charmed.”

“And this,” Houghton said, placing a hand on his wife’s stomach, “is Ramsey.”

“Or Lance.” Annabelle looked at Clifford. “He’s dying for a girl.”

Two housemaids began the service of a three-course dinner after Clifford, Houghton, Annabelle, Montgomery, and Harold had taken their seats at the polished table. Clifford noticed that the wine for the evening was older than him. The flatware was fine silver, and the stemware was lead crystal. Over the next hour and a half, Houghton talked about PanCola, how he chose white for the label because that had been the color of the show globe in his father’s store, that he believed consumers enjoyed the drink more for its cool temperature than for its sugar content, in addition to carrying on about his family, Monty’s gift for sports, Annabelle’s business acumen, Haddy’s love of solitaire. Between courses the boys thumb-wrestled. During coffee Annabelle inquired amiably about Clifford’s background.

Later that evening, tipsy from the wine, Clifford telephoned his editor and, holding a copy of Sinclair’s The Jungle in his free hand, told him this story was going to be more complicated than he had thought.

Born and raised in Mississippi, Snowden Wright has a B.A. from Dartmouth College and an M.F.A. from Columbia University. He has written for The Atlantic, Salon, Esquire, the Millions, and the New York Daily News, among other publications, and he previously worked as a fiction reader for The New Yorker, Esquire, and The Paris Review. Wright’s small-press debut, Play Pretty Blues, was the recipient of the 2012 Summer Literary Seminar’s Graywolf Prize. He currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia.