Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features an original chapter from Crystal Hana Kim‘s debut novel If You Leave Me. A moving story of love during wartime, the novel’s poses difficult questions about whether it’s better to choose security over love and safety over freedom. Here, Kim shares her thoughts—and an example of a wholesale chapter revision—on revising a multiple-perspective work, and on the difficulty of squaring significant historical and social events with a particular character’s personality.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features an original chapter from Crystal Hana Kim‘s debut novel If You Leave Me. A moving story of love during wartime, the novel’s poses difficult questions about whether it’s better to choose security over love and safety over freedom. Here, Kim shares her thoughts—and an example of a wholesale chapter revision—on revising a multiple-perspective work, and on the difficulty of squaring significant historical and social events with a particular character’s personality.

—

If You Leave Me is about five characters growing up during and after The Korean War. The book begins in 1950 with Haemi Lee, a sixteen-year-old Korean refugee who has fled her home with her younger brother and widowed mother to find safety at a makeshift refugee camp in Busan. There, Haemi reunites with her childhood friend Kyunghwan and meets his older cousin Jisoo, who is from Seoul. As If You Leave Me progresses, it follows these characters (as well as Haemi’s younger brother and eventually, her daughter), as they are shaped by this civil war and the turbulent years of modernization that follow.

Since the novel alternates between five first-person narrators and spans sixteen years, I played around with perspective a lot. Here is a scene that I ended up cutting and rewriting from a different perspective.

—

Excerpt from the original “Kyunghwan 1964” chapter:

Aejung wasn’t Hyunki, and I wasn’t a savior. I was just a fuck endangering her life. The rain made us unwieldy, and I insisted that we carry umbrellas. We walked until we reached City Hall, where the roads converged into a straight path north to where the protest began. Guards stood packed together there, commanding us off the plaza grass and away from alleyways. The look on their faces was enough to make me stop.

I pushed Aejung against an empty storefront and held my umbrella across her chest. “We should go back.”

“We’re close.” She pointed to the thick mass near the government buildings. I could hear their anger; I could feel it beneath our feet. “Just to there, where everyone is.”

“You won’t reach it. Look at all the people—it’s not going to stay peaceful.”

“Let me go.”

I stayed her with the umbrella’s hook. “I won’t go with you.”

“Then don’t.”

Men ran past us. I pointed to a military truck further up. It parked and spewed helmeted policemen with clubs. In their thick, dark uniforms, they rounded the edges of the demonstration. “Those fucks are going to arrest as soon as one person gets violent. It’s not worth it.”

“We won’t get caught.”

“You know what they do to girls?”

She broke away from my grasp. Already wet with rain, her skin was slippery and yielding. She stole easily into the crowds. Maybe I let her go. I imagined her in a war. How effortlessly she would have gotten killed.

I left the umbrellas. I ran past lingering cars, a grandmother hurrying south. Storeowners watched from windows with splayed fingers, like children ready for a parade. Once I was into the thickness, part of the mass, there wasn’t room to see anything but the damp heads of those pressed in front and all around. Protestors yelled: “Fuck the regime!” “Our country can’t be sold!” “Down with Park! Down with corrupt government officials!” I looked for a red bracelet, for hair falling out of a cap. The scent of oranges stained onto small, childlike hands.

Trucks continued to hound at the edges, unable to make headway into the crowd. The policemen waited, whether from fear or from faith in their numbers, I couldn’t tell. Ahead, a protestor in a shiny zippered jacket sat on the shoulders of someone else. They turned to us, the man below walking backwards as the man above waved his hands. “Death to Japanese Imperialism!” He rallied us into one chant, one giant’s voice.

We thronged north, at times pushed forward by the force of others more than by our own feet. For a moment I remembered the start of the war, when we had fled south in hordes that also kept us moving. How scared I had been of the deaths around us, the unknowing. How I had deflected desperation and hunger with scientific names: for the clouds, trees, the vegetation we passed along the way.

Someone cried out. The sound cartwheeled to me from underneath the clamor. A grandfather with wire-framed glasses and a bald, wet head, crouched and bleeding.

“Hit by a rock,” the boy next to me said. We stopped in front of him, diverting the stream of walkers. “Hold this up.” The boy gave me his banner, untucked his rain-soaked shirt. “Hold it higher.”

I felt like an idiot, but I hoisted the banner above our heads. He tore a long cotton strip from the hem of his shirt and wrapped it around the old man’s head. They concentrated on each other: one through a steady whispering of thanks, the other with quick, assured hands.

“How far is this going?” I asked them.

“To the Blue House.”

“All the way.”

“I’m looking for someone,” I said.

They didn’t pay attention to me. The boy took back his flag. The old man rose, cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted.

I tried to sift through the crowds, searching for Aejung. I thought I saw Hyunki—his tall frame and strange face. A bridged nose punched red. His voice, graveled from all those years of coughing, shouting at the police. I looked away. I searched.

So why did I cut this scene, and how did I rewrite it? At this point in If You Leave Me, The Korean War has been over for eleven years. Kyunghwan, who lives in Seoul and has cut ties with Haemi and Jisoo, is coping with the end of an affair. In terms of South Korea’s historical timeline, I knew an important political protest happened in the summer of 1964, and I wanted to capture the event in my narrative. How would I weave this historical protest into my novel? Since Kyunghwan lives in Seoul (while Haemi and Jisoo live in the countryside), I decided to make him go to the protest.

However, as I began writing the “Kyunghwan 1964” chapter, I found it difficult to write the protest scene because Kyunghwan is a character who is apathetic and afraid of political loyalties. He copes with the violence of his youth by becoming impassive to politics, focused on survival rather than confrontation. How could I get someone like him to attend the protest? I decided that Aejung, the high school daughter of the family he rents his room from, would be his avenue in.

However, in the completed scene above, it’s clear that Kyunghwan is not interested in the protest, which translates to a scene that is not interesting to the reader. If your character isn’t compelled by their own actions, why should the reader care? Apathy in the character can create apathy in the reader.

I ended up cutting the whole protest from Kyunghwan’s chapter. I allowed him to hear of the protest, but instead of attending, he gets drunk and reexamines the end of his affair. This felt much truer to his personality, his equivocating nature.

I still wanted to touch upon this important historical event though, so I added a whole new chapter after “Kyunghwan 1964,” which is told from Hyunki’s perspective. Hyunki, Haemi’s younger brother, is a college student in Seoul at this point. South Korea’s college students were becomingly increasingly politically active, and this was the perfect fit. (Why didn’t I think of this sooner? I’ve asked myself this question many times. Who knows how the writerly brain works.)

—

Here is an excerpt of the protest scene, now from Hyunki’s perspective:

We met the rest of our classmates on the main square of campus, where they’d gathered on the wet, mown grass. We assembled naturally according to class, with the fourth-years guiding the front. Atop a stone statue, the student council leader shouted through his cupped hands, “March west and then north to Gwanghwamun!”

We whooped and spread out along the road, blocking trams and pushing against one another in a half jog, more than two hundred of us buzzing with eager insistence. Jinho and I raised the Taegeukgi between us. Sungsoo and Byungchul clutched their signs to their chests to keep them dry. The rain made us unwieldy. We were too frenzied to notice.

Byungchul prodded my back. “How’re you feeling now?”

“This is better than any hangover soup,” I shouted.

We marched past lingering cars, a grandmother hurrying south. Storeowners watched from windows with splayed fingers, like children ready for a parade. When we reached City Hall, the roads converged into a straight path north and the mass thickened into thousands. Students from universities across Seoul, men in smudgy work uniforms, others with raincoats over their suits, we all came together. Each group chanted its own slogans. We couldn’t hear our group’s leader over the throng.

“Straight through to Gwanghwamun!” Sungsoo called, reining in the second- and first-years. He waved his sign to hold our attention. “Watch your surroundings!”

We threaded along the eastern edge of the crowd, following Sungsoo’s sign. The din vibrated around us. Sungsoo shouted again, only a meter ahead, but his voice was buried too quickly.

Jinho pointed to our right. Soldiers, gripping guns and cudgels, stood packed together. “I told you,” he yelled into my ear. I caught a guard’s eyes. His expression was blank, removed of all emotion. He had the fatty cheeks of youth, but he didn’t flinch when a protester yelled “Our country can’t be sold!” right into his face. Whether the soldiers waited from fear or faith in their numbers, I couldn’t tell

This protest scene feels more vibrant, urgent, and necessary. Hyunki and his classmates are eager to join the throng, despite the soldiers surrounding them. The added benefit of writing this scene from Hyunki’s perspective was the ability to write more specifically about the political backdrop, since he would have been well-informed of the reasons leading up to the protest. Through his eagerness to be part of the fray, I was also able to heighten the sense of impending violence as the protest continued.

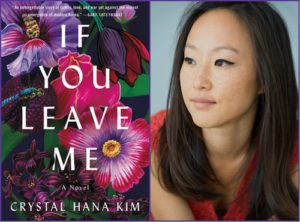

Crystal Hana Kim’s debut novel If You Leave Me was published in August 2018. It was longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and named one of the Top 10 First Novels of the year by ALA Booklist. She was a 2017 PEN America Dau Short Story Prize winner and has received scholarships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Hedgebrook, Jentel, among others. Her work has been published in The Washington Post, Elle Magazine, The Paris Review, Electric Literature, and elsewhere. She is a contributing editor at Apogee Journal.