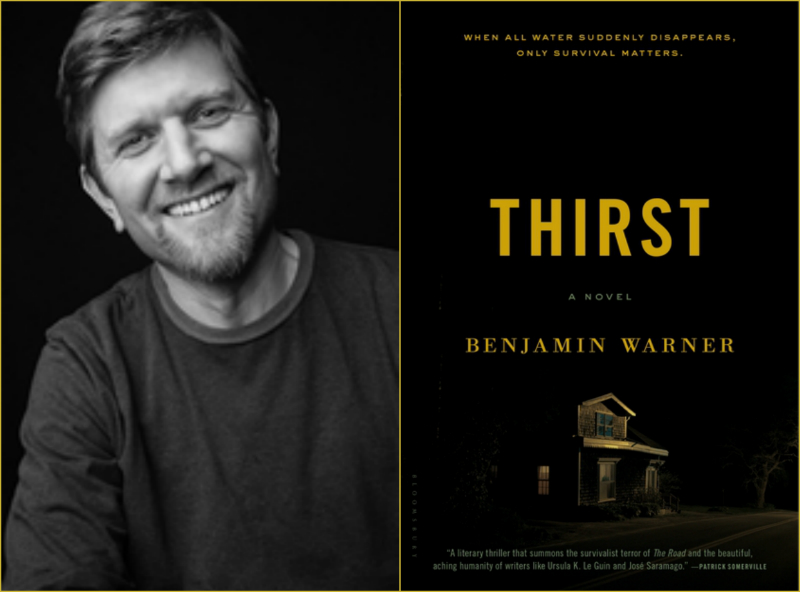

Editorial Outtakes is a feature in which we publish excerpts from novels and story collections that you won’t find in the finished books because, prior to publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene by Benjamin Warner, whose debut novel, Thirst, was published by Bloomsbury last week.

Editorial Outtakes is a feature in which we publish excerpts from novels and story collections that you won’t find in the finished books because, prior to publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene by Benjamin Warner, whose debut novel, Thirst, was published by Bloomsbury last week.

An intense, literary novel with the pacing of a thriller, Thirst is first and foremost a novel interested in asking us the question: what would you do in order to survive?

—

Before my novel had an editor at Bloomsbury, it had two agents, Christy Fletcher and Sylvie Greenberg, both of them working hard to get it into shape. As I understand it, this is the way the publishing world often works now; an agent does double duty, first getting it ready to submit to an editor at a publishing house, and then—once it has reached that point—working more truly as an agent and selling the thing. I got really lucky, in that both Christy and Sylvie are excellent at both of those jobs.

Early on, they read several drafts of Thirst in a relatively short period of time. This was generous of them, of course, but it did to their editorial eyes what it did to mine . . . it blurred them a little. After the third or fourth read, they both thought the same thing: It still needs something. This is advice I’ve received—and given—before, knowing that it’s basically the equivalent of hands thrown in the air. There comes a point in the revision process, no matter how concerted, that the muscles of a critic hit a wall. For me, it’s not unlike that feeling of having run too far and eaten too little. A discombobulation sets in.

Christy and Sylvie resorted to doing what I’d done originally in giving it to them: they found another reader.

This reader didn’t know me and didn’t know much about the book. I didn’t know him. Not even his name. When he reported back to them, I was disconnected from his literary sensibility, his tone of voice, and his mood when he told them, “Eddie (the main character) seems too closed off in his perspective.”

And though I didn’t agree, or necessarily even understand what he meant by that, it was something I could run with, something I could implement. I spent the next several months writing the story from a second point of view, that of a retired engineer who lived down the street from my main characters. This man’s wife was a devout Christian, and the two of them were very protective of the teenaged girl who lived directly across the street, a girl in a wheelchair. When the crisis of the novel hits, the girl’s parents don’t return home from work, and the engineer and his wife take her in to look after her. For eighty pages, I followed the increasing frustrations of this couple. The man, Steve, is competent and sensible, but stymied by forces beyond his control. He watches helplessly as his wife suffers. He watches as the neighbor-girl chooses to go it alone, rejecting his protection. He goes out into the world, himself, looking for help—and the world treats him pretty poorly.

I spliced that point of view into the novel, alternating it with the main character’s “closed off” perspective. When I sent the draft to my agents, they passed it along to their new reader—the reader who’d launched me on the project of this parallel narrative. Of course, there was no way for me to know what this reader’s face looked like as he read the new offering with (I was told) great disdain, but I imagined him wearing the same expression as I dangled him by his ankles from a high bridge.

It turned out that what the book really needed was a new ending. I scrapped those 80 pages. I fixed the ending. The book was picked up.

But I’m not so sure that would have happened had I not written those superfluous scenes. And though I imagined his shrieking demise, that nameless reader did me a great service. What he’d asked me to do was more fully understand the universe I was describing. Echoes of those pages are left in the published draft—some of those characters were absorbed into the characters who remain, and pieces of them are simply there, unspoken, like ambient weather I haven’t described but can see clearly in my head.

Before I’d gone through this process, I’d often assigned an exercise to my students where I asked them to write a scene from their characters’ lives either years before or years after their stories have taken place. It had to be a scene that could not possibly make it into the story. I asked them to do this, telling them it was something that writers do—on a regular basis!— never really having done it, myself.

When I finally did, I was angry I’d been asked to.

Looking back, I’m happy that it worked.

—

When Claire got home, she was with Eileen and they both looked healthy and perspired from the sun.

“Oh, Steve,” Claire said. “You have to see what Rick is doing with his tomatoes. He’s got them trained onto a trellis. They look so organized you forget what bushy messes they can be. Even with the blight.”

“Water’s out,” Steve said. “Phones are dead, too. Eileen, can I check at your place? My system’s fine. It must be on our block.”

“It’s out at the Thomas’s, too,” Eileen said. Eileen was taller than both Claire and Steve, and had dry, strawberry blond hair that looked clean and pretty in spite of her disregard for that sort of thing. Claire had told him that Eileen must have been very beautiful in her youth, and that it must have been a very stately kind of beauty. Steve trusted she was right. Eileen was his neighbor, and a good one—a good friend to Claire.

“Let’s check your place, just to be sure,” he said.

They walked across the yard and Steve waited just off the porch step as she fiddled with the key.

“Come on in,” she said. “I hope it’s not out for long. I have a bucket of green beans I want to blanch. I can’t eat that many raw. It gives me indigestion.”

She flipped her living room switch up and down.

“Try the tap,” Steve said.

She went to the kitchen and tried it. Steve heard the dull thump of the metal handle and then nothing.

“Nope,” she said. And then, “It’s too hot in here already. I may just sit this one out in the shade until the evening. I’ve got my lemonade if Claire wants to join me.”

“I’ll let her know.”

“Now we just wait and see, I guess?”

“WSSC knows when they have problems with the pipes. They have sensors that hear when one’s about to break. They’re probably tearing up the asphalt right now. You have enough to drink in here? Besides the lemonade?”

“Sure. I have a gallon of milk I just bought… let’s see.” She opened the door onto her refrigerator’s dim interior. “I’ve got prune juice, not that anyone but me would drink it. Carrot juice. I’ve got a little wine spritzer if you and Claire feel like toasting.”

“Keep the door closed if you can. You’ll lose the cool.”

Back home, Claire was sitting in her chair with her Bible on her lap. She’d given up reading the paper with him, but would watch the evening news if he had it on.

“You know,” she said. “I used to love when the power went out. It was like camping.”

“What are you reading?”

“Noah. Listen to this. The Lord then said to Noah, “Go into the ark, you and your whole family, because I have found you righteous in this generation. Take with you seven pairs of every kind of clean animal, a male and its mate, and one pair of every kind of unclean animal, a male and its mate, and also seven pairs of every kind of bird, male and female, to keep their various kinds alive throughout the earth.”

“I hadn’t remembered the seven pairs,” he said.

“Me, either. It’s interesting. Lucky number seven.”

“I’m going to check on the Clarks,” he said.

“They won’t be home.”

“Lisa will be.”

Across the street, he’d worked with Eric Clark for two weeks cutting boards for Lisa’s ramp. That’s when they’d first moved in, and Lisa was only twelve years old, but even then she was already an expert in her chair.

Steve used the steps. After they’d built the ramp, he’d walked it once, alone, and the door had opened on him halfway up. He’d felt like he’d been caught kicking up his heels. That was the last he’d used it.

Lisa opened when he knocked. At sixteen, Steve was struck each time he saw her by how quickly she’d outgrown her braces. It wasn’t in her breasts or hips, but behind her eyes—a dark intelligence, almost world-weary. Where did she get it? Besides school, she hardly left the house.

“Hi, Mr. McCarthy,” she said.

On the back of her chair, she’d affixed a silver pompom—a remnant from a home football game in the fall when the cheerleaders had taken her out onto the field at halftime. Steve and Claire had been in the risers that night, right alongside her parents. He remembered looking at Susan as she dabbed harshly at her eyes with a paper towel.

“You got power?” he said.

“Nope. It sucks.”

“Read a book,” he said, looking beyond her into the house’s dark living room. “When do you go back to school?”

“Another month. I just finished my book.”

“Which one?”

“The Odyssey.”

“For school?”

“No. For fun.”

“And?”

“You know why everyone loves these kids’ books that get made into movies? The heroes are girls.”

“Hmm…” he said.

“I’m just saying.”

“You have enough to drink?”

“We have stuff in the fridge.”

“You come see me and Claire if you need anything.”

“Okay, Mr. McCarthy.”

He went back across the street and told Claire that she was fine.

“Her father will be home soon. He comes home a few hours early on Fridays. It’s sweet that you worry about her.” She was still tucked into Genesis. She’d been into the Old Testament for a while now, getting back to her roots, as she called it. Steve found it interesting. She hadn’t been raised in the church. It was a new thing for her.

“She’s practically a woman,” he said.

“And it’s good she has role models like you.”

He humphed.

“Role model,” he said.

Benjamin Warner teaches creative writing at Towson University. He is the editor of Voices and Visions, a literary magazine for the homeless community in Maryland. He holds an M.F.A. from Cornell University. Thirst is his first novel. A native of Annapolis, Maryland, he now lives in Baltimore.