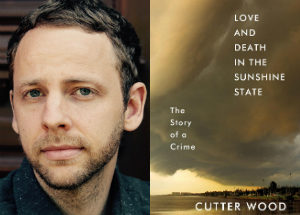

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a scene from Cutter Wood‘s Love and Death in the Sunshine State: The Story of a Crime, an account the 2008 murder of Sabine Musil-Buehler. Wood’s investigation is augmented by a more personal story about the nature of love and intimacy. What results is a deeply moving work of true crime set against the hot incandescent backdrop of Florida’s Gulf Coast. A book that’s as much about human fallibility as it is about murder, Love and Death in the Sunshine State explores the nature memory, love, and the enduring power of writing. The book was published last week by Algonquin Books.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a scene from Cutter Wood‘s Love and Death in the Sunshine State: The Story of a Crime, an account the 2008 murder of Sabine Musil-Buehler. Wood’s investigation is augmented by a more personal story about the nature of love and intimacy. What results is a deeply moving work of true crime set against the hot incandescent backdrop of Florida’s Gulf Coast. A book that’s as much about human fallibility as it is about murder, Love and Death in the Sunshine State explores the nature memory, love, and the enduring power of writing. The book was published last week by Algonquin Books.

—

A Chapter on Fear

Like the living room that lay beyond it, like the hallways, like the people, and like everything in that house, the door was tall and white and narrow. Its paint was peeling, and there was no sign of ornament except that it had a white porcelain knob, webbed with gray lines and seated loosely in its socket. It was this door, always left barely ajar, at which I listened timidly to see if it was safe to enter. The room behind it was long and hardly twice as wide as a hallway, and at the far end were two large south-facing windows. The light that passed through the swirling panes of these windows was already weak at that time of year; it entered the room only reluctantly, serving not so much to bring the objects out of obscurity as to outline all the things one couldn’t see, and before these windows, my grandparents sat as still and dark as two silhouettes.

To my left when I entered, a television crackled quietly. Positioned there opposite my grandparents it played only golf or sometimes those tireless commercials for unnecessary household devices, mayonnaise openers, handheld wood chippers. So different were these programs from my beloved cartoons, that I half doubted whether this television could even receive normal broadcasts, and with two quick steps I ran by it. I crossed the room, passing doors on my left and right, doors always closed that led to the bathroom, the laundry, the front hall and the dusty, abandoned parlor, and at last I sat down in the darkness at my grandparents’ feet. The carpet, whatever it had once been, had been worn down to an indiscriminate color and texture. Rough and pilled in places, rubbed flat in others, it smelled of the sweat of dogs, and though I know now that dogs don’t sweat, it can’t change the fact of the memory or that I only ran my hand along the back of that carpet as one runs a hand down the flank of a hound.

I didn’t look up at my grandparents because their faces were in shadow and because, anyway, I didn’t need to. I knew what they looked like. My grandfather, lanky and angular, the skinniest of his brothers, forever dressed in slim khaki pants and a cardigan striped in shades of brown, in one pocket of which was a roll of chocolate covered caramels wrapped in gold foil. His glasses were of the variety popular ten or twenty years prior, with a wide tortoise-shell band across the top, from which hung two thick, armor-like lenses, and the contraption was supported on his large, arched nose. My grandmother sat motionless beside him in her recliner, her white hair frozen in a shock atop her head, a little coagulated wetness in the creases at the corners of her mouth and at the corners of her eyes. She was motionless save the occasional movements of those eyes as they followed me across the room.

The house was empty. Outside, the days were moving toward fall, and the squirrels were scrabbling fiercely with each other for the last of the year’s walnuts. We sat there the three of us like this, having finished an early dinner—baked beans into which my grandfather had sliced a hot dog—and finally, he reached into the table at his side and withdrew the gray book, with its little golden emblem, and began to flip through its pages. The smell of those pages, yeast and dust and crumbling glue, and the sound they made as they grazed his fingertips; I had already begun to associate these sensations with Poe, and I waited for the story to begin.

“The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as best I could; but when he ventured upon insult, I vowed revenge. You, who so well know the nature of my soul—”

“No, Pop, we already read that one.”

“All right.” The sound of paper fluttering once more. “There are certain themes of which the interest is all-absorbing, but which are too entirely horrible for the purposes of legitimate fiction. These the mere romanticist must eschew, if he does not wish to offend or to disgust. They are with propriety handled only when the severity and majesty of truth sanctify and sustain them. We thrill, for example, with the most intense of ‘pleasurable pain’ over the accounts of Napoleon’s crossing the Berezina, of the earthquake at Lisbon, of the plague at London, of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, or of the stifling of one hundred and twenty-three prisoners in the Black Hold of Calcutta. But in these accounts it is the fact, it is the reality, it is the history which—”

“Pop, we read that one.”

“‘The Pit and the Pendulum?’”

“No.”

“Then ‘The Black Cat.’” And he would clear his throat, as I still do before a story, and begin. “For the most wild yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief.”

His voice was slightly nasal, and because he had been a judge maybe or because he enjoyed this ritual, he read slowly and softly. Every word received its full and exact pronunciation, every comma its due breath. Slowly, almost imperceptibly then, the sun hid itself in the bare branches of the oak outside the windows, branches whose shadows reached down the walls, catching all of the objects in the room, ourselves included, in a fine black lace, and it was in this fecund net of darkness that the sentences began to sprout into the distinctive, ornate, and ridiculous voice of Poe; little by little, darkness overtook the light, just as illness overtook the mind of the story’s speaker, and it seemed that in one of the house’s rooms, I could just make out the sound of someone pacing or of bells on a jester’s hat. I leaned my head against my grandfather’s knee, which through his stiffly starched slacks was bony and still, and as I followed Poe’s sentences into ever-deeper spirals, I at last ceased to think at all. Or better to say my thoughts merged exactly with the words of Poe, and I became the character in the story, listening to himself in horror and powerless to stop the evil to which he was bound. Or then the frame slipped again and now I was the author and Poe, whose picture I had seen in the encyclopedia, with his high forehead and imperious stare, was only a character in a murder I myself was constructing, and we keeled off drunk with ill intentions into sleep.

Suddenly, my grandfather moved his knee, only slightly, and the artifice of the dream shuddered and peeled away like paper to reveal the black living room. He turned on the lamp beside him, but the high ceiling soaked up its light, leaving only a little of it in a patch around the couch. Outside, the sky was just a pale blue argued over by branches. It never occurred to me then to wonder how long my grandfather sat with me there, with my head against his knee, though the room had obviously been too dark to read for quite a while.

At last he would ask me to get the wheelchair. With caution, because I could no longer be sure that we were alone, I padded into the front hall, where the chair’s two huge wheels glistened in the dark and returned rolling the awkward device before me. I positioned it in front of my grandmother, pushing down two small levers on either side so that the locks bit into the rubber wheels, while my grandfather hoisted her up and placed her into it. Once she was settled, he’d drape a sweater over her shoulders and push her out into the yard to take the air.

Then, left to fend for myself in the house, my head still spinning with Poe, I was forced to creep through the dark rooms and make my way to my bed upstairs. There was no good means to do so. It wasn’t a large house, but due to the additions made by each successive generation and the incomplete conversion to electric light, the hallways were an unlit labyrinth. They led this way and that in total darkness, turned back on themselves, deposited you where you’d begun and sometimes trapped you in a dead end with nowhere but a shallow linen closet to hide.

You could mount the dirty back stairs, but at the top you were deposited in a long hall with a mirror at the far end in which your shadow rose to meet you. The only option then was the front stairs, though these were hardly better. They had been built steep, to conserve space, and they were deeply bowed so that each step cried out beneath your foot. I climbed them slowly because at the landing, in a stark black frame, was an oil painting of my grandfather’s great-great grandfather, the man who had settled the family in Muncy and promptly died of fever. The portrait looked as though it had been painted from the corpse. He wore a plain black jacket with a high collar and a white silk scarf tied so tightly around his neck that it seemed to be holding his head in place. His forehead was high, his black hair swept to one side, and drained of blood, his cheeks were sunken and his skin waxy. The moon, which in my memory shines eternally in the front window and onto that painting, raised a glare off the yellow forehead, and the eyes peering out from their skullish hollows followed my every step. Still worse was the nose, a large sharp nose, unmistakably the nose of my grandfather, unmistakably my own nose, and below it the thin barely discernable lips that seemed, if you removed your eyes from the portrait, to curl at the corners. I mounted those stairs, wanting only to run as fast as I could but not daring to take my eyes from the painting, drawing up finally before it, almost nose to nose with it on that miniscule landing, and then backing up the rest of the stairs one by one until I gained the second floor and could flee in a flash, with a bang of the door, down the hallway and into my room.

Because I could not convince myself that the painting was simply a painting and not a living, scheming thing, and because I was a hopeless coward, I eventually developed a mechanism by which to survive the trial of going to bed in that house. First, I imagined that there existed some sort of community between all things evil. Not too difficult for a child who has listened to a preacher discourse on the legions of the devil. Once I had accomplished this act of make-believe, I had only to pretend that I myself was one of the monsters haunting those halls. In this way was I able to traverse that house at night without fear. Now when I climbed the stairs at night, I did so as the very epitome of evil, wearing on my face the same sallow grin as the dead man in the picture. I no longer looked at him until I reached the landing, glancing over then only casually before going the rest of the way to bed. It would not have been unusual, had you stationed yourself very discreetly in some dark corner of that stairwell, to see a small tow-headed boy, back hunched, hands curled into talons, climbing the dark stairs and as he crossed through the patchwork of moonlight thrown across the landing, nodding with a faint conspiratorial snarl at the art.

I have heard it said that one of the advantages that books enjoy over film lies in the former’s paucity of detail, since even in the most baroque Victorian novel, where every room is described with livid, stultifying attention, almost nothing is accomplished, in terms of description, compared to the briefest moment in a television show. Because of this, so the logic goes, as we read we are forced to provide our own sets, and in so doing we avail ourselves of those which are most readily available, hiding with Polonius behind the curtains in our aunt’s living room as we eavesdrop Hamlet’s soliloquy or placing the door to the secret garden in the ivy-covered wall behind our house. Based on this they claim—who claim? booksellers, no doubt—that books will always be more immediate, more terrifying than film. Only in a book does the killer actually appear in your own bedroom.

I don’t know if the stories we read in newspapers abide by these same rules or whether the form fear first takes remains with a person throughout his life, but as I drove up and down Anna Maria talking to those who’d known Sabine, I began to recognize the original inkling of fear, of an imagination beyond my own control, that I’d first discovered with my grandfather and grandmother and Edgar Allan Poe. Or to put it another way, it was as though I had opened one of the many doors in that living room in Muncy and stepped not into the front hall or the laundry but as a fully-grown man onto the beach in Anna Maria. I could not shake the sense that at any moment I would turn and find myself back in one of those high, dark hallways, at the end of which I’d see a woman’s nightgown disappear around the corner.

—

Love and Death in the Sunshine State is about a woman named Sabine Musil-Buehler who disappeared from a small island off the Gulf Coast of Florida. It follows the course of her relationship with William Cumber in the months before her disappearance, and it also follows my investigation of the disappearance and my faltering attempts at building a relationship of my own during that time. Early on as I was interviewing William Cumber, I had a moment of clarity (always suspect) where I realized that all of the stresses in their affair were simply extrapolated versions of those in more mundane relationships. For a variety of thematic reasons (my grandfather was a judge with very peculiar ideas about justice; my grandmother had also disappeared, albeit in a different manner), I became convinced that my grandparents’ relationship was the perfect counterpoint to William and Sabine’s relationship.

I wanted this to be part of the book so hard (I still do), but on the first call with my editor, she brought up a different line in the text, in the very last chapter of the book, where I briefly mentioned my own relationship. What was that about, she said. I think I laughed and said, Don’t get me started on that. I remember there was a pause on the other end of the phone line, and in retrospect, I can now hear her putting a checkmark in a small mental box. Of course, she did get me started on that. I’d always known that was where the book was headed (that’s why I put it in the final chapter, I told myself), but I thought I could get there without doing all the messy work of actually describing my own experiences as I was looking into Musil-Buehler’s disappearance. My editor had me develop that thread in the narrative, and the bigger it got, the more evident it became that the portion of the book devoted to my grandparents was some sort of vestigial organ. This section was a holdout for a long time. It so perfectly described for me the way we protect ourselves from fear by becoming the feared object, and it also reminded me of the feeling I had when I was down in Florida walking around late at night trying to figure out who’d killed Sabine Musil-Buehler. I kept this section, and I kept keeping it, even as I cut everything else to do with my grandparents, and then one day this went, too.

It was important, though, and I still return to it from time to time because I can see now in its pattern the shape of the material that was to take its place. It was in writing this section that I first felt I was beginning to strike on the tone of the book. That boy on the stairwell landing, fingers curled like claws, he’s my narrator.

Cutter Wood completed an MFA in nonfiction writing at the University of Iowa, during which he was awarded numerous fellowships and had essays published in Harper’s and other magazines. After serving as a Provost Fellow at UI and a Visiting Scholar at the University of Louisville, Wood moved to New York. For his forthcoming book, Love and Death in the Sunshine State, he was awarded a 2018 Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He currently lives in Brooklyn with his wife and daughter.