Editorial Outtakes is a feature in which we publish excerpts from novels and story collections that you won’t find in the finished books because, prior to publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene from King of the Worlds, the new novel by M. Thomas Gammarino, which tells the story of Dylan Greenyears, a has-been Hollywood heartthrob whose best days are seemingly behind him. After losing the lead in Titanic, Greenyears has left with his family for a recently settled exoplanet, New Taiwan, where he plans to live a quiet existence as a prep school teacher. As you can imagine, things don’t quite go as Dylan expects them to. Here’s Gammarino on the book, his process, what he had to cut (and why he cut it), as well as the deleted scene itself.

Editorial Outtakes is a feature in which we publish excerpts from novels and story collections that you won’t find in the finished books because, prior to publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene from King of the Worlds, the new novel by M. Thomas Gammarino, which tells the story of Dylan Greenyears, a has-been Hollywood heartthrob whose best days are seemingly behind him. After losing the lead in Titanic, Greenyears has left with his family for a recently settled exoplanet, New Taiwan, where he plans to live a quiet existence as a prep school teacher. As you can imagine, things don’t quite go as Dylan expects them to. Here’s Gammarino on the book, his process, what he had to cut (and why he cut it), as well as the deleted scene itself.

—

Beginnings are tough. I generally try to heed Kurt Vonnegut’s advice and start my novels “as close to the end as possible.” The hazard there is that, after a propulsive initial scene or three, I’m then tempted to go back and start filling in backstory, and I have an unfortunate tendency to overindulge in that. Actually it’s not such a bad practice insofar as it forces me to get to know my characters better before dragging them though a world of pain, but it would be nice if I could train myself to recognize the ultimate dispensability of those passages even as I write them. Instead I spend months bad-faith-believing in them until inevitably I’m forced to concede that unless digression is going to be my game, à la Tristram Shandy, I can’t just tuck a whole bildungsroman between paragraph breaks without expecting readers to lose sight of what the novel they’re reading is actually about.

This problem was doubly vexed in King of the Worlds since the novel is in some ways about retrospection itself. Dylan Greenyears, an everyman high school teacher living on an exoplanet 2001 lights years away, is desperate to recapture his former glory as a celebrated actor on Earth. Given that premise, it follows that I’d have to dramatize some of what those halcyon days themselves were like, but the backstory of that backstory, the rags-to-riches tale of Dylan’s becoming a celebrity in the first place, is at a kind of twice-remove from the ground story, and this was where I found myself doing entirely too much writing. Dylan’s film career effectively begins when, as an extra in 12 Monkeys, he has a chance encounter with director Terry Gilliam.

In early drafts of the novel it took me 7,000 words to get Dylan from starring in a high school musical to meeting Gilliam in that donut line. In the novel as published, I get the same work done in about 500 words. The difficult trick is to liposuck all the fat, keeping only the essentials and spreading them out over the whole novel rather than simply plopping them down all at once. If you’re going to remember just one thing from this introduction, this should probably be it: “Spread, don’t plop.” I dare say it’s at least as useful as that old chestnut “Show, don’t tell.”

Still, even murdered darlings are darlings, and I rather like those 6,500 words I cut. I won’t burden you with all of them here, just a tidy, self-contained 3,500 or so that still live between the lines for me in that submerged, nine-tenths-of-the-iceberg, Hemingway way. And given that this novel is so much about the movies, it feels especially appropriate that those words should see the light of publication in what amounts to a literary outtakes reel.

And so:

—

King of the Worlds>Menu>Special Features>Outtakes>

“How Dylan Greenyears Landed an Extra Gig in 12 Monkeys“

A couple of weeks after all the graduation parties, when the thrill of early summer had gone, Chad talked Dylan into accompanying him downtown so that they could register with an acting agency and finally gain entrée to the biz. He’d torn out a little ad from the classifieds section of the Inquirer.

ACTORS WANTED!

Have you ever dreamt of being in the movies? Wolfowitz Talent Agency currently seeks new talent. Walk-ins welcome.

That was it, the whole ad. It didn’t even list an address—they had to look in the Yellow Pages—and that elusiveness actually heightened the allure of the place somehow. It was as if they’d stumbled on a treasure map in the attic.

Dylan told his mother they were off to look for summer jobs, which wasn’t technically a lie, and then they got into Chad’s Trans-Am, drove up City Line to West Chester Pike, and followed Walnut Street under the El into the throbbing heart of the city they’d spent their whole lives on the periphery of but barely knew anything about. Soon they would live here, in this murder capital of brotherly love, and it was thrilling to watch the manicured lawns give way to pavement, increasingly uneven and cracked, ruins of some Italian cobbler’s American Dream. Then came the graffiti that their parents loathed and they loved, jagged flowers, brash and explosive and not-for-sale real, and then the skyscrapers looming like some vague promise over all the row homes. The avenue swelled, and now they were gunning right for those futuristic blue-glass cathedrals, and old City Hall with its statue of William Penn, who was a guy who had done some stuff, and now they were entering the roundabout with no clue where they’d be spit out. They had an address was all, and no plan beyond making it downtown.

So they pulled over by the Greyhound Station and asked a guy who was selling soft pretzels. They couldn’t hear what he said over the noise of a departing Boston-bound bus, but they could see he was telling them to go the other way, and since all the streets were one-way, they knew this meant going over a block and then doubling back. And then Chad figured out that the first number or two of a street address indicated the block, which was nifty, and so once they got to the right kinds of numbers they’d have a fifty-percent chance of going in the direction of the proper cross street. Naturally, they chose the wrong way the first time and went miles too far before feeling sure of that, so they drove over a block and then back the other way, and then, finally, they spotted their number in gold against a gray edifice. They parked in the lot next door and made their way through the blaring sunshine to the Wolfowitz Talent Agency.

Chad opened the door and they crossed the threshold, blood thrumming with myth. The directory in the lobby indicated that the agency was on the seventh floor, and despite what had just happened in Oklahoma City, security was still pretty lax in American skyscrapers, so no one bothered them on their way up. They got out of the elevator, walked down the hall, and found the door. “This is it,” Dylan said. He wanted to peer in the window to see what they were getting into, but there was no window to peer in, so he pushed the door open, and into the future they went.

The Wolfowitz Talent Agency was not unlike a dentist’s office, with a cold, pretty secretary at a desk and six people seated in the waiting area flipping through tattered magazines. Four of the other people were girls, two were dudes, all were white, and all were roughly the same age. The dudes looked like they belonged in a boy band, tough in the wussiest way possible.

“Um, hi?” Chad said to the secretary, who reflexively handed them a couple of clipboards and asked them to fill out forms. She didn’t even look up from the paperback she was reading.

“You together?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“You have headshots?”

“Headshots?” Chad echoed.

She handed him a business card: “Starlight Photo Studios/Professional headshots.” A cursive font at the bottom spelled out, “Ad astra per aspera: through effort to the stars!”

Dylan was confused. “So do we need to do this first or . . . ?”

She finally looked up from her book. “Meet with Mr. Wolfowitz, then give them a call. They can usually take you same-day. Tell them we sent you and they’ll give you a discount.”

“So we’ll just sit here and wait then?”

She rolled her pretty eyes and went back to her book. Nice lady.

They took their seats among the other aspirants and filled out their forms. Where it asked for acting experience, they proudly listed their roles in the high school musicals.

When they were done with the forms, they flipped through copies of a magazine called On Stage as if it were one they were familiar with and read all the time, and they whispered to each other nonchalantly about the headshots, which were in fact inducing quite a bit of panic. Dylan had sixteen bucks on him, but Chad said he probably had enough in his ATM account to cover them both if Dylan promised to pay him back soon. Dylan promised, though he had no idea where he was going to get the money. His dad gave him some petty cash now and then, and a credit card to use for gas, but that was pretty much the whole of his income.

When it was their turn, the secretary led them into Mr. Wolfowitz’ office. Mr. Wolfowitz was a middle-aged, goateed, potbellied guy in a pinstripe suit and wingtips—more or less exactly what Dylan had expected. He didn’t stand up or shake their hands or anything gracious like that but glanced down at their applications and nodded to himself. He said, “So you want to be actors?”

“More than anything in the world,” Dylan said.

Chad nodded his accord.

“Good-looking fellas,” Wolfowitz said.

The boys blushed and exchanged a giddy, sidelong glance.

“Let me level with you, gentlemen,” Wolfowitz went on. “I see a lot of faces in here, and a lot of them are so goddamned good-looking I want to drop my drawers on the spot, but sex appeal alone ain’t enough to cut it in this business. And neither, frankly, is talent. No siree, if you want a shot at showbiz, you’ve got to have some X factor—star power, you know, whatever you want to call it. And finding that, finding that, boys, it’s not an exact science by any means. And yet I do it. Time and again I do it, like one of those guys who find water veins under the ground. And do you know what my secret is?”

They shook their heads.

“I use one gauge and one gauge only . . . ” He left them hanging.

“What is that?” Chad asked.

“My epidermis.”

“Epidermis,” Dylan said. “Like, skin?”

“That’s precisely what it is. As far as I’m concerned, you could look like a goddamned Greek god and act like Meryl fucking Streep, but if your energy doesn’t have an immediate effect on my largest, most exposed organ, then I’ve got no use for you.”

Dylan braced himself for the letdown.

“But you fellas,” Wolfowitz continued, “you fellas have been tingling my follicles in all the right ways from the moment you stepped in here. I could feel it as soon as you entered the room. You boys horripilate!”

“Really?” Chad said.

“What do you think, I make this stuff up?”

Dylan could feel himself blushing, his ears going hot.

“Let me cut to the chase: I want to represent you.”

Holy crap! Nothing in Dylan’s experience as an actor had prepared him to think things would unfold otherwise, but it still seemed too good to be true. Did he really horripilate?

“Now I’m going to need those headshots ASAP so I can begin shopping you around.”

“We were going to take care of that right after this,” Chad said.

“Good. That’s good. And then of course there’ll be the usual registration fees. Normally I need five hundred right up front from each of you, but I’m willing to take a loss on you guys in the short term because the ions in here are telling me you’re a good investment. Let’s make it three hundred, what do you say?”

“Three hundred dollars?” Dylan asked.

“No, three hundred Chihuahuas. What the fuck do you think?”

“Um, we don’t have that kind of money right now,” Dylan said. “We don’t have jobs or anything…”

Chad made a face like he wanted Dylan to shut up.

“Look, fellas, are you serious about this or not? If you want me to work my tail off giving you a shot at the big time, I’m going to need some kind of symbolic gesture on your parts. Three hundred dollars is not a lot of money. Tell you what, let’s call it two hundred. Can you handle that? Christ, go mow a few lawns. On the other hand, if you’re just playing around with me here, then please quit wasting my time, would you?”

“We’re not playing around,” Chad assured him.

Wolfowitz looked at Dylan.

“We’re not,” Dylan said.

“Words are words, fellas. If you’re serious about your futures, then come back within the week with headshots and four hundred smackers. We’ll take it from there. Capiche?”

They nodded.

“Now tell my secretary to send in whoever’s next, would you?”

So that was it. They had their marching orders and were being kicked out.

“Thank you,” they said in awkward unison.

“Jinx,” said Wolfowitz. “One of you go buy the other a Coke. Bye-bye now.”

They made their way down the elevator and through the lobby in stone-cold silence. Outside, the sun poured down like whiskey on the street. They walked over a block before Dylan finally broke the silence: “So what did you think?”

“That guy was fucking awesome,” Chad said.

“And he liked us,” Dylan said.

“Liked us?” Chad said. “That guy loved us.”

“So we should go through with this then, you think?”

“You’re joking, right?”

“No.”

“Why in God’s name would we not go through with this?”

“I don’t know. Maybe on the off chance that he says what he said to us to everybody.”

“Unbelievable, Dylan.”

“What is?”

“That you’ve got so little faith in your own talent.”

“No, but I mean this is a business, right? He’s in it to make money.”

“Dylan, think about what you’re saying for a second. If Wolfowitz is a scam artist, wouldn’t it make sense for him to go out of his way to make us feel good? Instead, this guy just warned us to stop wasting his time and kicked us out of his office. What scam artist would do that?”

“I don’t know, a sophisticated one maybe? Look, I’m not saying I think he’s a scam artist necessarily. I just wonder if we shouldn’t do a little research before we hand over four hundred bucks to the guy.”

“Well the dude’s obviously been doing this a long time. If he were a fraud, don’t you think he’d have been shut down by now? And did you see all those autographed glossies on the walls? I’m pretty sure I recognized some of those people. What more do you want?”

“I guess you’re right,” Dylan said.

“Trust me on this one,” Chad said.

And indeed, it was comforting for Dylan to place his faith in Chad, who was so certain of their future success that he always spoke as if it had already happened.

“So where are we gonna get the four hundred bucks?” Dylan said.

“We’ll think of something.”

“Well let’s go get our headshots done anyway.”

They dropped by a 7-11 so that Chad could use the ATM. They also bought themselves some soft pretzels and Snapples, and while they lunched on the sidewalk, they speculated about the meaning of stickers on a nearby phone booth informing them that “Skateboarding is not a crime” and “Andre the Giant has a posse.”

It was only when they got to Starlight Photo Studios that Dylan knew for sure what he’d vaguely suspected until now: a headshot is just a kind of photograph. Call it a “headshot,” though, and it acquires some magical allure, seems like something only a specialist is qualified to make, but the grim truth was that they were about to pay a hundred bucks each for somebody to take their pictures. It wasn’t lost on Dylan, of course, that having their headshots taken would initiate them into a new tribe, specifically the tribe of people who’d had their headshots taken. Obviously, not all people in the headshot tribe ever gain admittance to the professional actor tribe, but nearly all members of the professional actor tribe must be members of the headshot tribe first, so it was in their best interest to bite this particular bullet.

The US economy was rather robust back in those days, so they had an easy enough time finding jobs—so easy, in fact, that they got the very first ones they applied for, at the Borders Books and Music on Baltimore Pike. They applied to work in books and were hired in the café, which was close enough. Between them, they’d need to cover seven shifts a week.

Dylan liked working at Borders. For one thing, all the espresso drinks that had become so popular in the past half-decade were finally demystified for him. Barring some esoteric points, the only thing distinguishing a latte from a cappuccino was the milk-to-espresso ratio—who knew? Their manager, a sexagenarian who rode a Harley, trained them, via videotape in the break room, to pull shots with a “golden crema” and foam the milk just so. She also encouraged them, with their “beginner’s minds,” to come up with their own drinks to complement the standard menu. Chad and Dylan rarely worked the same shift, but when they did, they thrilled to experiment with different concoctions. Their finest hour saw the invention of the “Chai-o-hazard,” which consisted of six shots of espresso dropped in a large chai latte. It was high-octane, totally nasty stuff, and as a result, the drink was quite popular among the high school set.

Dylan also enjoyed making small talk with customers. He got to know many of them by name and memorized their drink orders. There was hot Mikaela, who worked at the bank next door and ordered a large hazelnut latte; there was the balding polymath, Greg or maybe Craig, who ordered a small Americano and studied Korean all morning; there was Tom Spinerelli, an old classmate of Dylan’s from Saint Francis of Assisi grade school, whose father had recently died and who sat around and talked about reincarnation, synchronicity, and Zen with this retired guy named Marco who ordered something different every day and always left a pile of New Age books on the table for Dylan to put back at close. Dylan didn’t mind so much, because the other reason he liked working at Borders was the same reason anyone who enjoyed working there would: he loved books. He and Chad were different in that respect. Chad wasn’t a reader, and on those few occasions when Dylan tried to talk to him about some book or other, Chad would just glaze over. That someone could love plays and not novels seemed strange to Dylan, almost hypocritical, but that was Chad for you. He’d never been very good at sitting still, and the truth was his love of the theater was a love of performance, not of drama per se. He’d be as happy in an infomercial as in Hamlet.

Between the morning and afternoon rushes in particular, there was nothing much to do. This downtime drove Chad crazy and he resorted to doing whip-its in the back, but Dylan would grab some books from the stacks and read. That was the summer he read Lolita, Dubliners, On the Road, and Childhood’s End, and in retrospect Borders would always stand as the high-water mark of American culture in his mind. No one knew back then how fragile it all was, how Omni was about to usher in a whole new paradigm. For a heady moment there, it was like the library of Alexandria was up and running again, and everyone had a card.

Within a few weeks, Chad and Dylan had their money. They drove back to the Wolfowitz Talent Agency and explained their situation to the mean, pretty secretary who told them that Mr. Wolfowitz was very busy but that she’d be glad to take their headshots and money for them. They handed them over, thanked her, and went back home. The whole thing was incredibly anticlimactic and they didn’t talk about it the entire way. Instead, they listened to the new Pearl Jam record and bitched about how it wasn’t as good as Ten.

It was a scam. Of course it was. They’d fattened Wolfowitz’ wallet by four bills for ten minutes of his time, and for all they knew he got some kickback from the headshots as well. In the couple of weeks following their remission of payment, this conviction grew in Dylan’s brain until he was effectively certain of it. Chad told him not to be so negative, but Dylan countered that maybe Chad could try being a tad realistic for once. Chad simpered. Dylan thought about going back down there and trying to get their money back, but his balls weren’t quite big enough. Wolfowitz would either tear him to shreds himself or call in some mobster cronies to do it. Better to cut their losses and chalk it up to bitter experience. He would never be so gullible again.

And then not twenty-four hours after Dylan had vowed not to think about the whole mess anymore, he returned home from work to find a Post-It note by the phone: “Dylan, a Mr. Wolfowitz called. From a talent agency? Said to call him back ASAP.”

Dumbfounded, Dylan dialed the number. He expected the secretary to pick up, so he was doubly surprised when Wolfowitz himself did.

“Mr. Wolfowitz? This is Dylan Greenyears. I got this message—”

“Dylan, son, I’m glad you called. None too soon either. Look, I’ve got this gig for you and your friend as extras if you’re interested. It won’t pay well, but you’ll get to be on a movie set and see how things work, maybe rub elbows with some stars. What do you say?”

“I say wow. Yes. Thanks so much for thinking of us.” Oh, the shame! He had so vilified Wolfowitz in his mind, and now the guy was turning out to be every bit the professional he said he was.

“Can you meet at the Broad Street entrance to the Convention Center at seven a.m.?”

“What day are we talking about?”

“Tomorrow. I know it’s short notice.”

“That’s okay,” Dylan said. “We’ll be there.”

“Excellent. Dress casual. Grungy, you know. Blue jeans, t-shirt, flannel, that sort of thing.”

“Okay, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“We’ll see you then.”

Dylan phoned up Chad straight away to tell him the good news.

“What did I fucking tell you! I’ll need to get somebody to cover my shift, but fuck, man, I’ll quit if I have to. You see! Believe in yourself and good things can happen. Do you believe me now?”

“We’re just extras,” Dylan reminded him. “And we don’t know the first thing about this movie.”

“Naysayer!”

He was just being realistic.

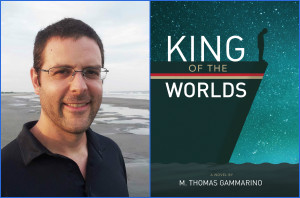

M. Thomas Gammarino is the author of the novels King of the Worlds and Big in Japan, and the novella Jellyfish Dreams. His short fiction has appeared in The New York Tyrant, Tinfish, Word Riot, and The Hawai’i Review and elsewhere. The recipient of the 2013 Elliot Cades Award for Literature, he lives in Honolulu with his wife and kids.