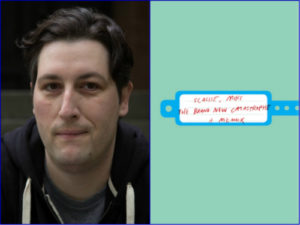

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features writer Mike Scalise, author of The Brand New Catastrophe, reflecting on some of the particularities of revealing character details in nonfiction. Given that we all grow up (and, presumably, learn a lot about ourselves and the world around us), how does a writer of memoir go about depicting their own naiveté and youth authentically? How does a nonfiction writer avoid creating one-note characters in memoir when so many of us—especially when we’re young—ring the same emotional bells time and time again? And how, when you’re sick, do you recognize and reconcile all of the other things that are wrong with your life? Scalise, who writes both fiction and non-fiction, shares a few of his thoughts on these matters here, and touches on some of the particular challenges of writing a memoir when you’ve got a lot of great fiction-writing advice kicking around your head.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features writer Mike Scalise, author of The Brand New Catastrophe, reflecting on some of the particularities of revealing character details in nonfiction. Given that we all grow up (and, presumably, learn a lot about ourselves and the world around us), how does a writer of memoir go about depicting their own naiveté and youth authentically? How does a nonfiction writer avoid creating one-note characters in memoir when so many of us—especially when we’re young—ring the same emotional bells time and time again? And how, when you’re sick, do you recognize and reconcile all of the other things that are wrong with your life? Scalise, who writes both fiction and non-fiction, shares a few of his thoughts on these matters here, and touches on some of the particular challenges of writing a memoir when you’ve got a lot of great fiction-writing advice kicking around your head.

—

We’ll start with the cut passage, which is a chapter-closing scene set in an Upper-Manhattan Hospital between twenty-four-year-old me and a member of my neurosurgery team the night before I’m about to have a very rare, bleeding brain tumor plucked from the inside of my skull:

—

When visiting hours ended, and a vibrant orange cloaked itself over the shoulder of the Hudson, one of my neurosurgeon’s underlings—an easy, rotund guy with a blond buzz cut—came into my room for one final, chummy pep talk. My parents were long gone and so was my sense of humor, yet still I showed him the stationery gifts I’d gotten from Jean the VFT Tech, with which my mother, father and I played several stilted games of tic tac toe before they finally left for the evening. He reviewed the next morning’s procedure—incision through the upper gums, out the door a few days later—and reassured me once more of the surgery’s relative ease.

“We’ve been buddy-buddy, which is great,” I said. “But you have to tell me, am I going to be okay here?”

“Yes,” he said. “Yes, yes, yes. Seriously: we do, like, eight of these a week.”

“How many result in dead people?”

“Very, very few,” he said. “You’ll be fine, dude.”

He patted my shoulder.

“So if I die,” I said. “It’s your fault then, okay?”

He took his hand off me, put his head down, flipped through my file.

“Just a joke,” I said. “Fucking around.”

“Not cool,” he said.

He didn’t look at me and tapped his pen against the side of his head.

“Yeah that’s not cool,” he said, “not at all,” then walked out.

I didn’t see him again after that.

—

One reason that scene failed to make it to the final version of The Brand New Catastrophe has to do what I’ve heard the fiction writer Laura van den Berg (Find Me, The Isle of Youth) call a character’s rate of revelation—which is a much cooler way to say “what a writer gives away about a character, when, and why.”

Rate of revelation, if I understand van den Berg properly, works as a tracking mechanism across the terrain of a story. It happens, largely, in revision. First, a writer interrogates every instance in which a character reveals a personality tic or a quality that’s crucial to the story. Then, the writer zeroes in on emotional repetition of that tic or quality across an array of scenes, wipes them out, then replaces them with incremental, deeper revelations, which then peel back a character’s already raw skin, exposing something newer and more surprising across each scene, complicating and enriching that character, and ensuring the plot generates from those character revelations in organic, complex ways.

In other words, rate of revelation means making sure your characters aren’t one-note. Van den Berg talks about it only in terms of fiction, where the burden of “experienced reality” tends to weigh little on a work’s fidelity. But it’s an issue in memoir too, as I discovered in my first round of edits, which came back with a simple note from my editor on that chapter-closing scene with the guy with the blond buzz cut.

It said “I would cut this scene. The scene before [it] accomplishes the same work.”

The scene my editor referred to, which made the final cut, appears below. In it, my endocrine specialist, Dr. Parsens, visits me, bedside, to explain the irreversible havoc my bleeding tumor had wrought on my pituitary gland:

—

Parsens held up a sheet of paper on which she’d drawn a brain inside a head. On it was a scribbled dot labeled PITUITARY. She explained that the gland sits at the base of the brain, behind the eyes, the king gland of the endocrine factory. The pituitary was, she said, the silent dictator of our lifeblood, our body’s smallest, most prescient multitasker: at once an interpreter and a messenger. Along with the hypothalamus, it senses our potential for human experience, then triggers the glands in its employ to get ready, to prime our bloodstream with hormones that permit us to feel and maneuver our way through things like love, hunger, sex, and sleep fully and naturally with zero thought as to why. Without the pituitary’s commands, the rest of our endocrine system stalls, Parsens said, just a line of ready soldiers waiting for orders.

Next to PITUITARY on the diagram, Parsens wrote the words ANDROGENS and HUMAN GROWTH HORMONE. The second one she circled twice.

“The tumor is currently overproducing growth hormone and has been for some time,” she said. She went on to say that in a typical tumorectomy, GH levels—along with the rest of one’s hormonal portfolio—return to normal almost immediately. “But we don’t know for how long excess GH has been secreting, and we won’t be able to tell the kind of damage the rupture has done to the pituitary,” Parsens said. “Not until after.”

She detailed my future in the brain trauma wing as one of near constant tests and gaugings. Every word sounded like some jagged other-tongue, a montage of alien jargon that built to a dull momentum. Secretions. IGF-1 counts. Diabetes insipidus. Parsens wrote the words FOLLICLE STIMULATING HORMONES on her diagram and began talking about their functions, which were, I understand now, largely female and reproductive. But all I heard then were the words “follicle” and “stimulation,” which made me think quickly of my plain, smooth, face, one that looked far younger than my twenty-four years.

“Brass tacks,” I said. “Does this mean I’ll finally be able to grow a suitable beard? I’ve never been able to,” I told her. “Figured it was hormonal. Do we have that technology? Can we make that a reality?”

“That,” Parsens said, “is not how it works.”

—

There was no question my editor was right. Just track the movement across both scenes: a medical pro explains a process to me in a blatantly expository manner, then I misread the moment and respond with a joke, which bombs, cue the “Curb” music. There is no emotional progression from one scene to the next, nothing new or raw or kinetic reveled for the reader to chew on. It’s stasis, and the fiction writer in me knew it, and that part of me was embarrassed that the manuscript had gotten this far along with such an emotional redundancy.

But at the same time it posed a paradox between managing drama in a novel and managing it in a memoir, one that makes constructing organically satisfying scenes a difficult prospect: the obstacle of human obliviousness to their own predictability. The blind spot. These are the portions of a real-life tale, told through the mechanics of memoir, where the reader knows more about the emotional reality of a scene than its real-life author character. It’s a not-quite-identical version of dramatic irony that nearly every memoir writer contends with: how do I properly render how much I was not myself during this crisis? Very often, it means depicting (and sometimes reveling in) the kind of thing rate of revelation is meant to undo in fiction, and here’s why: in real life crises, people often revert to the same behavior patterns and defense mechanisms. Crises can turn us into skipping records of our own worst (and best) tendencies. I’m thinking here of how Darin Strauss structures the key event of Half a Life as a homing device that has such power as a crisis over its cast and timeline that regardless of what scenes unfold, it manages, always, to calls its characters firmly back to it. Or the Moby Dick-like, circular confrontations between Nick and Jonathan Flynn in Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, where one character changes but the other remains, very sadly, fatefully, the same. Stasis is, heartbreakingly, the mode in which many of our lives greatest dramas take shape. So how do you render it authentically while keeping organic character progression intact? How do you honor both the reality of the lived moment, and the Aristotelian needs of big-L literature?

For me, it became a question of emotional translation. The moment with the blond buzz cut doctor remains a very potent one for me, Mike the Real Human Who Lived All of This. I return to it so often when I think of that time, and the great loss that came from it. It’s the moment when, in real life, I at last sobered to the strange, awful future that lay ahead of me, took my first true assessment of it, and begged the closest person I had to a friend, who was no friend at all:

Am I going to be OK?

But in book life, that question had long been answered by the manuscript as a firm, solemn No. Not ever. I understood now that between real life and book life, certain truths and refrains must evaporate as a story prepares itself to meet strangers. As a writer I discovered that fifteen years after the events of that story, I still grappled with its shape as I did while I lived the events, and the stubborn, sad idea that I could still keep it all as I wanted. And I had to learn again, from those carefully tending to the realities of the story that I couldn’t see: That is not how it works.

Mike Scalise‘s work has appeared in Agni, Indiewire, Ninth Letter, Paris Review, Wall Street Journal, and other places. He’s an 826DC advisory board member, has received fellowships and scholarships from Bread Loaf, Yaddo, and the Ucross Foundation, and was the Philip Roth Writer in Residence at Bucknell University.