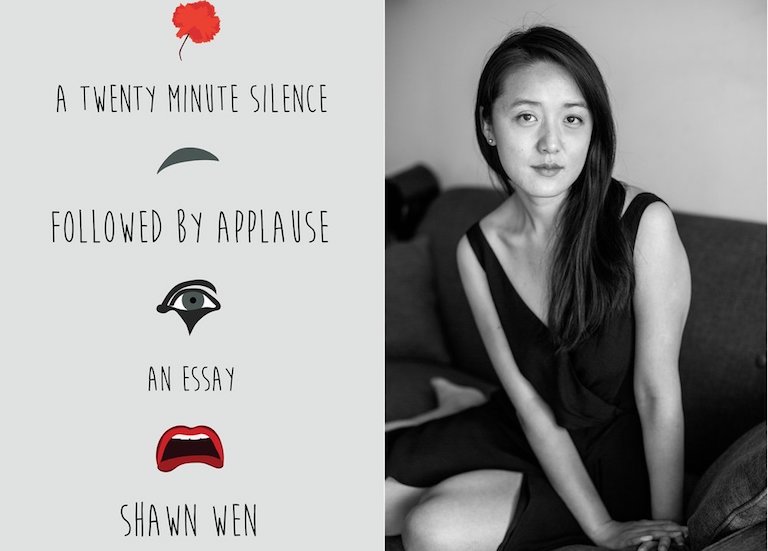

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features author Shawn Wen, whose A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause is a kaleidoscopic, book-length essay examining the life and art of Marcel Marceau. Published this week by Sarabande Books, the book is by turns a journalistic endeavor, an imaginative inroad into the artist’s world, and a history. Like Leslie Jamison, Wen is a rigorous investigator. And like Maggie Nelson, her prose is artful without being precious or gaudy. Throughout, Wen carefully pulls her subject into focus for the reader, even as she acknowledges the contradictions and complications inherent to Marceau’s legacy.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features author Shawn Wen, whose A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause is a kaleidoscopic, book-length essay examining the life and art of Marcel Marceau. Published this week by Sarabande Books, the book is by turns a journalistic endeavor, an imaginative inroad into the artist’s world, and a history. Like Leslie Jamison, Wen is a rigorous investigator. And like Maggie Nelson, her prose is artful without being precious or gaudy. Throughout, Wen carefully pulls her subject into focus for the reader, even as she acknowledges the contradictions and complications inherent to Marceau’s legacy.

—

I never saw Marcel Marceau perform in person. I first read about him in his obituary, and its odd, disjointed biographical tidbits are what set me on this project. So at the heart of this book about Marceau there’s an absence. What emotion or energy of live theater that exists in A Twenty Minute Silence Followed By Applause is borrowed or imagined.

The summer I was 21, I spent my afternoons on the third floor of the New York Performing Arts Library. In this chilly, muted room, I passed the time watching reviewers’ reels and combing through clippings. Not a bad way to escape those sticky New York summers.

Occasionally, my experience in the archives found its way into my writing. In these discarded texts, I reference crude camera tricks, my own wobbly suspension of disbelief, and the puny sort of immortality that video allowed Marceau.

But ultimately, I didn’t want to overburden this book. So we cut the sections dwelling on the nature of theater versus the nature of film, as well as some detailed explanations of Marceau’s mime technique, which were probably only interesting to me.

I did have a hard time cutting this Marceau quote: “Mime needs perfection. When you’re in a play, fifty percent is the genius of the actor, fifty percent is the genius of the author. When a mime is not perfect, you see nothing.”

It gets at his obsessiveness, his tireless touring, his immaculate technique. To me, this perfectionism connects back to the idea of seeking immortality through film and is underscored by the chaos and war of his youth. But including so many of these loaded and somewhat histrionic quotes threatened to capsize my slender little book.

When I show this book to friends, we sometimes laugh nervously at how thin it is (and, in the same breath, how long it has taken). But the book’s own compact body speaks to the energy that my editors and I put in to cutting entire pieces of the book and tightening it. We tried to avoid slumps, repetition, and unnecessary exposition.

This work is especially porous, pitted by many intentional absences. Of course, language is by nature impoverished when it comes to describing a mime performance—an art form that from the outset refutes speech. I wanted to play with that dynamic, tease at the inherent contradictions in writing on mime.

That said, I did wince when I cut the quote, “I am like Ulysses.” I like these moments where he’s didactic and grandiose. I know men like that; I’ve dealt with them before.

—

M.’s insistence

But the mime Marcel Marceau insisted on being filmed. “Films deal with reality. You can go back to them. The theatre always runs away; who remembers the great stage actors of the past?”

His performances rely on caricature and stylization. Like in an impressionist painting, distance aids in the illusion. But the camera is a magnifying glass that turns his painted face into a giant distortion. You can clearly see the pancake makeup, the fake eyebrows drawn over real ones, his constant mugging.

“When I am dead, they revive.”

The footage is self-conscious. As he lifts weights, invisible forces push down him. Burdening his shoulders. Buckling his knees. Atlas did not look so different, cradling Earth on his back.

“I am like Ulysses.”

Bip struggles against wind that isn’t there. He conjures this force by stiffening his body. Ducking against the strength of the gust. Digging his heels into the black stage floor. He brought this wind here. He controls weather itself. Sky and water submit.

Circus routines

Bip looks up at the sky towards the tightrope platform. The staircase is a technique from the theater teacher Etienne Decroux, creating the illusion of height and distance. Marceau holds his arms parallel in front of him, grasping the rail with both hands. He ascends one step at a time.

“My feet exactly measure a concrete distance between one step and the next higher and my body must feel as if I [am] actually marching up real stairs.”

He looks out from his high platform, then nervously down. Throws his arms out for balance and puts one foot on the tightrope. His leg shakes, knee rattles. Scared, he retreats back to stable surface.

He bows to the audience and tries again. His whole body convulses as he steps out, leading this time with the opposite foot. He hops forward on his right foot and swings his left, propelling ahead on the rope as he desperately looks for a point of balance. He turns ninety degrees to face the audience. Both feet on the wire now. Knees spring up and down. Arms flapping like wings trying to catch an air current. He jumps with both feet leaving the wire, and then catches himself again. His body still bouncing, limbs vibrating, he starts one direction, then turns his body 180 degrees in the other—both ends of the platform seem equally far away. He begins to lose his balance, throwing his arms back to catch himself. Hops and lands on the platform. Bip immediately recovers his dignity and takes a bow.

His high-wire illusion uses the virtuoso technique he learned from Decroux, but Marceau’s personal additions are caricature and comic relief. He adds the emotional drama: the tightrope walker’s nerves, fear, desire to avoid embarrassment, and final satisfaction.

“Strangely enough, I have been a real tightrope walker in my life,” Marceau said. “And people were not so scared seeing me walk on a real tightrope as they were watching me walk on tightrope on the floor.”

***

For the next act, he first gestures that his assistant is a beautiful woman. He uses surprisingly crude shorthand, drawing an hourglass figure in the air. Before he begins the routine, the knife thrower takes a minute to sigh and look at her.

Now he shakes hands with the beauty and tells her where to stand. It’s time. He pulls daggers out from his shirtsleeves, his pant legs, his shoes.

On darker performances

Marcel Marceau said, “When I started, I hunted butterflies. Later, I remembered the war and I began to dig deeper, into misery, into solitude, into the fight of human souls against robots.”

In “The Trial,” he scurries back and forth across the stage. He is defendant, prosecution, defense, judge, jury, and all the witnesses. The prisoner arrives in chains. Attorneys yap manically. The jurors deliver a guilty verdict. And the judge’s face glowers without forgiveness.

In “Bureaucrats,” a visitor walks through an office labyrinth. He is an innocent outsider. He meets one useless drone after another. It is a maze peopled with zombies.

And then, on faded video, our performer struts under the backdrop of a crescent moon. He is a sculptor chiseling at a statue. In earnestness, he hammers until there is nothing left.

Bip as Don Juan

Don Juan is making out with some girl. There’s something rather sloppy and sexed up in how Marceau kisses in this performance. Children use the same moves to ridicule intimacy. With his back to the audience, he wraps his arms around his torso so that his fingers peek out under each armpit. It’s as if we’re looking at the hands of his lover wrapped around his back. He shimmies his shoulders up and down, so that both their bodies writhe in unison. Gross.

Next is a woman perched on a balcony. He throws up a rope and climbs to her. After planting a big kiss on her lips, he begs her to come down and join him. In a show of gallantry, he bends to pick her up, but her weight sends him staggering. He stumbles back and forth and then sets her back down.

This is the logic of mime. Gravity applies. His teacher Decroux had said: “Watch dancers on the stage pretending to carry a grand piano. They rejoice in the hollowness of the pretense. They trip along. The piano has no weight. Now watch mimes going through the same act. They present precisely the weight of the piano by indicating the strain it occasions.”

But the fat girl is also Marceau’s frequent gag. Bip lusts after remote beauties, only to end up with an unappealing gordita. Though she’s invisible to the audience. Thin as air! We register his disgust, and then she’s gone, as quickly as she arrived.

Marcel Marceau gave interviews on the history and importance of mime. He appeared on talk shows. He wrote forewords to books. He recorded an album. His crusade, his obsession, was to prove that mime was an art form unto itself. He tired of the questions: Why didn’t you go into traditional theater? Why didn’t you go into dance?

He said, “Mime needs perfection. When you’re in a play, fifty percent is the genius of the actor, fifty percent is the genius of the author. When a mime is not perfect, you see nothing.”

War Memories

He was just sixteen when the Nazis invaded. Sixteen when he left home. Sixteen when his father died. Sixteen when he went into hiding. And so, of course, this story is so markedly unlike Bip’s other misadventures. The soldier story is the account of a young man’s life interrupted. He calls this performance “an outcry against any war.”

Bip performs rifle drills, and his handling is off. He finds the gun too cumbersome and heavy. But he falls in line, marching along in goosestep as the soldiers call cadence.

The filmmaker here employs a crude special effect, kaleidoscoping the image of the actor. One Bip turns into four, all marching in unison. They multiply again. Seven Bips stack on top of each other in a honeycomb formation. It’s a tediously literal metaphor about war’s obliteration of the individual.

A gunshot rings out, and the Bips stop midstep. All seven Bips throw their hands in the air: don’t shoot. Another gunshot goes off, and the Bips hit the floor. We hear a spray of bullets, and the camera zooms in on a singular Bip once more. Our hero, face down with his fingers plugged into his ears.

The screen fades to black. We see Bip against a bleak gray backdrop. There’s the sound of shells flying overhead. Bip advances forward in a low prowl. His stovepipe hat is a few feet away on the ground. He reaches for it, and the sound of a gunshot responds to the sight of his naked, extended hand. He tries again and again. On the third attempt, he grabs the hat but his thumb is blown off.

Compared to cinema, mime is so stylized, so clean. Marceau folds his thumb behind his palm, to make it appear as if it was taken off by the bullet. There’s no blood or gore, just a missing digit. He studies his hands in disbelief. He pauses, closes his eyes mournfully, and holds his hands together. As he pulls them apart, the thumb is back. Mime logic. He sighs with relief and says a quick prayer.

In a moment of apparent madness, Bip stands up and begins walking. He’s plainly giving himself away to the enemy. Cheerful music begins to play, and the trilling sound of birds and insects resumes. He seems to be hugging his beloved. He takes her hand and begins to dance. Mid-step, he’s shot in the side. With one arm, he clutches his wound. His other hand is still raised in a large gestural dance move. He drops slowly. On his knees, he doubles over backwards.

Again, the filmmaker employs a basic camera trick. This time, he creates the mirror image of Marceau, a transparent ghost transposed over himself. These specters slowly stand up, their limbs splayed and dragging. He holds his arms out and begins to spin backwards, away from the camera, a ghoulish dance of chaos.

After all, Marceau had not fallen in love with Charlie Chaplin’s voice. No one loved Charlie Chaplin for his voice, high-pitched and nasal, piercing the air. Talking brought about the end of his career.

Words last, though. Words are printed, archived, remembered. “He quotes Chaplin so frequently you imagine he had dinner with him last night,” Robert Butler wrote of Marceau.

A gesture exists in the moment. And then the next gesture, the next moment. Each fleeing as quickly as it came. And then gone.

Words stay. If the word could summon a body. If the word could bring back the dead.

Shawn Wen is a writer, radio producer, and multimedia artist. Her writing has appeared in The New Inquiry, Seneca Review, Iowa Review, White Review, and the anthology City by City: Dispatches from the American Metropolis (Faber and Faber, 2015). Her radio work has broadcast on This American Life, Freakonomics Radio, and Marketplace, and she is currently a producer at Youth Radio. Her video work has screened at the Museum of Modern Art, the Camden International Film Festival, and the Carpenter Center at Harvard University. She holds a BA from Brown University and is the recipient of numerous fellowships, including the Ford Foundation Professional Journalism Training Fellowship and the Royce Fellowship. Wen was born in Beijing, raised in the suburbs of Atlanta, GA, and currently resides in San Francisco.