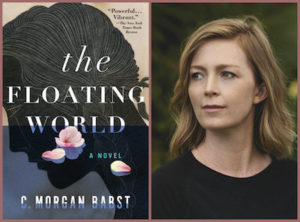

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene from novelist C. Morgan Babst‘s debut The Floating World. Published in 2017 and out this month in paperback, Babst’s acclaimed story of life in New Orleans following the destruction of Hurricane Katrina has been hailed as a poetic and tragic family tale with the narrative momentum of a literary mystery and the heart of a Faulknerian domestic drama. Here, Babst shares her thoughts on having to cut the storm—the novel’s central and grounding tragedy—and a beautifully written scene that never made it to press.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior the publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features a deleted scene from novelist C. Morgan Babst‘s debut The Floating World. Published in 2017 and out this month in paperback, Babst’s acclaimed story of life in New Orleans following the destruction of Hurricane Katrina has been hailed as a poetic and tragic family tale with the narrative momentum of a literary mystery and the heart of a Faulknerian domestic drama. Here, Babst shares her thoughts on having to cut the storm—the novel’s central and grounding tragedy—and a beautifully written scene that never made it to press.

—

When my novel went on submission, it was almost 200,000 words long, or more than three times Raymond Chandler’s 65,000-word ideal. The Floating World was not pithy crime fiction—well, there was crime in it, but of the less-than-pithy variety; still, triple The Big Sleep and you’ve got too much book. Triple The Color Purple, if you’d prefer. Triple The Virgin Suicides. Whatever you triple, it’s too much book.

For a while my agent, the lovely Meredith Kaffel Simonoff, who had already tolerated too much book from me too many times, passed on only rejections, all coupled with the some variation on this note: “This novel needs cutting, but I can’t see how.” Just as I was beginning to despair, Meredith forwarded me a different kind of message, from Andra Miller at Algonquin: “this book is the sh$%,” she wrote. I immediately copied that on a Post-it and pinned it to my wall. Three months later, Andra and Algonquin had optioned my manuscript. Not bought it. Though the book may have been the sh$%, it was still too long.

Andra, though, knew what to do about it. In the editorial letter she sent me, she noted that “The storm sagged.” This threw me for a loop. Hurricane Katrina was the center of the book—the plot’s fulcrum, the structure’s metaphoric antecedent, the manuscript’s literal middle third. I’d written the novel because, when the levees broke, my understanding of the world broke with them. Did safety exist anywhere? Was it possible to care for others without doing them harm? Would my city ever recover? It sure looked like its people would not. For years afterward, I wrote (and wrote and wrote), trying to figure all this out. In the storm—the real one I’d lived through and the one I’d imagined—people had lost their minds, their families, their homes, their lives. But the storm, Andra was saying, was boring. It sagged.

Luckily, my friend Sarah, who’d read the manuscript with great kindness, lived down the block. She and her dog were at my door within minutes of receiving my SOS. As we walked around the neighborhood, our dogs investigating all the lampposts, she let me rave, agreeing with my every point so wholeheartedly that, eventually, I started to argue the other side.

“Would Andra tell me the storm sagged if it didn’t?” I said, suddenly full of the wisdom of the workshopped.

“No,” Sarah said, contemplative, “but the storm is important!

“But if the storm is so important, why did I start the book ‘Forty-Seven Days after Landfall’?”

“Because,” Sarah explained to me, “what interests you is the aftermath! For there to be an aftermath, there has to be a storm.”

“Okay, so maybe there has to be a storm,” I conceded. “But does eighty percent of the ‘storm’ section have to take place in the evacuation? It doesn’t even rain on them in Houston!”

Her dog pulled her to the curb to bark at dachshund across the street. Keeping tension on his leash, she shouted, “Don’t you have a Post-it note on your wall that says An evacuated city is an automatic ruin.”

That Post-it, quoting Andrei Codrescu, was right next to the one that said This book is the sh$%: my top two Post-its.

“Okay,” I said. “But New Orleans is the evacuated city. And I’m using up 60,000 words in Houston and New York.”

“That’s your experience though,” Sarah said, taking a drag of her cigarette, furrowing her brow. “You evacuated.”

“I did,” I said, accepting sympathy. “But do I really have any business being in my own book?”

“But it’s your book!” she yelped.

“But other people have to read it, Sarah!”

Sarah is a very good friend. She nodded and hugged me and left me on my stoop.

The book was too long, in part, because I’d saddled myself with too many voices—three generations of New Orleanians, five points of view. As soon as I got home, I opened a duplicate draft and deleted four voices from the “storm” section—the four voices that reflected my experience of evacuation, the four voices that had been most cathartic to write, the four voices that had made the storm sag. Now, all that was left of the storm section was the storm itself, and Cora, the one character directly traumatized by staying, whose catatonic absence makes the story spin. Right away, my structure was both tighter and more thematically sound. It was like I’d planned it all along.

I wasn’t done yet, of course. Some of what I’d cut—important bits of plot and character—had to be bundled into flashbacks in the post-storm narrative. This worked out too, intensifying the sense of loss and regret that characterize the Boisdoré family’s crisis—but there was still too much book. Next, I cut inessential characters, then ineffective scenes, throwaway sentences, extraneous words. I got very, very good at cutting, an essential skill that I had, until then, lacked.

I am, I acknowledge, an over-writer—it’s an incurable disease, but preferable, certainly, to writers’ block. In fact, I like that my first drafts are always much, much, much too long. These are the drafts that know everything, contain my subconscious, absorb rage, allow experiment. They’re full of awful sentences, overdetermined, overwrought. But the too-long draft rewards rewriting, a process that boils down what is raw and watery into a concentrated and (I hope) intoxicating brew.

When I handed in the final copy of The Floating World to Algonquin, it no longer had my personal story in it. The bag I’d packed when I left New Orleans—three shirts and three skirts, five books, and one pair of painted heels—was gone, as were the stalled cars on the bridge over Lake Pontchartrain and the purgatorial McDonald’s off the road. The manuscript was lighter by 73,000 words—or one copy of the Catcher in the Rye—and I was lighter, too. There was less to carry as I left the storm behind.

—

Outtake from The Floating World

Joe threw his father’s bags into the back of the truck. The sun glared off the paint and the dust-clouded window. Long day ahead. Across the parking lot, the nun pushed his father—who could damn well walk, he kept saying—and the wheelchair’s spokes turned like second hands.

He looked up at the speeding clouds. Good thing his father wasn’t all there, he thought. The trouble he’d have to go through if he was. The nun and he each took an arm, something sack-full-of-kittens about Vincent, and hauled him up into the passenger seat. The nun pushed his father’s legs into the cab. Joe shut the door, thanked her.

His father had not been one to evacuate. Watching the weather, he would have put on his military face. I don’t care what that pissant of a mayor has to say. You think I’m going to abandon everything I’ve worked for because of some rain? When the last one—Georges, Juan, something—had threatened, his mother had already been sick, and they couldn’t be left alone, so Joe’d brought his family to Ozone Park to ride it out. The girls had spent the morning playing on the levee in the wind, while they’d filled up the bathtubs, put batteries in the flashlights, got out the cards and bourbon. Then, the next morning, they’d had to let Vincent tell them he’d told them so. This time, though, it was Joe’s call.

He climbed into the driver’s seat, shut the door.

His father was staring through the windshield. “You taking me home?”

“No, Pop. We’re going to evacuate.”

“I don’t see any call for that sort of language.”

A Lincoln SUV, full of children and luggage, a bird in a cage, was pulled up under the nursing home’s overhang. The old woman waited in her wheelchair as the man opened the hatch and shoved her small overnight bag into the stuffed compartment. Joe pulled out into the street.

“It’s mandatory, Pop.”

“Mandatory—” Vincent blew a raspberry, spangling the window with spit. “I’ll do what I like, eat what I like, go where I like.”

“And today, you’ll like going to Houston.”

“Houston?” Vincent pulled at his belt.

“You leave that be, Pop.”

He plucked at it, grinned. Joe fingered the little glassine pouch with the four Valiums the nurse had given him “in case of need.” It could set him back a year, Tess would say before she flushed them. He wondered what a year would do. His father writhed against the belt, and then, suddenly, sat still. Looking Joe straight in the face, he clicked the red release button. Joe jerked the truck into the parking lane.

“You stop that right this instant.”

Vincent fumbled with the locks, long fingernails scratching vinyl. “You let me loose!”

“I will not,” Joe said. “There is a hurricane coming, and you will evacuate. You will sit still, you will be calm, and you will be safe.”

He had stopped fumbling now, and he looked Joe in the eyes. “They called you?”

At the Shell station on the corner, the line for the pumps was only three deep. “What?”

“They called you? From Havana? They called?”

Joe sighed heavily. “I don’t know what you’re asking me.”

“Then how do you know?”

“Know what?”

“About the storm.”

Joe idled into the gas line. No one had known Betsy was coming until it was too late. Camille had lifted people up inside of their houses—including his Aunt Pauline—and scattered everything to the wind.

“We can see it, Pop. On the radar,” he said. “Get out while the getting’s good.”

His father shook his head. “You can’t see no storm before it’s come.”

Joe pulled up to the pump, slammed out of the truck. The flow of gasoline jolted on. Inside the car, his father was squawking like a chicken. Run, chicken little, was what he meant. Run, you think the sky is falling. Joe put his hand in his shirt pocket, and held up the bag of pills, V’s punched through them like little hearts. He left the gas running and stalked across the lot for a bottle of water to wash them down.

C. Morgan Babst studied writing at NOCCA, Yale, and NYU. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in such journals as the Oxford American, Guernica, the Harvard Review, LitHub, and the New Orleans Review, and her piece “Death Is a Way to Be” was honored as a Notable Essay in Best American Essays 2016. She evacuated New Orleans one day before Hurricane Katrina made landfall. After eleven years in New York, she now lives in New Orleans with her husband and child.

You can read additional Editorial Outtakes from writers like Shawn Wen, Mike Scalise, and Benjamin Markovits here.