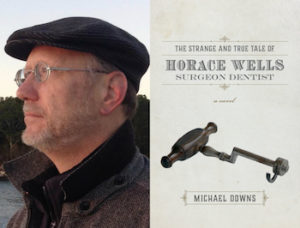

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features two outtakes from The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist, a novel by journalist and fiction writer Michael Downs. An account of the life and times of Hartford’s Horace Wells, the dentist who discovered that nitrous oxide had the power to alleviate pain during surgery, the novel investigates and imagines its way into an often fraught and sometimes scandalous historical record. An addict, an obsessive researcher into the nature of pain, and a criminal, Wells comes to life in this dark and engaging historical novel from Acre books.

Editorial Outtakes is a series in which we publish excerpts from recent books that you won’t find anywhere else because, prior publication, these sections were cut. This installment of Editorial Outtakes features two outtakes from The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist, a novel by journalist and fiction writer Michael Downs. An account of the life and times of Hartford’s Horace Wells, the dentist who discovered that nitrous oxide had the power to alleviate pain during surgery, the novel investigates and imagines its way into an often fraught and sometimes scandalous historical record. An addict, an obsessive researcher into the nature of pain, and a criminal, Wells comes to life in this dark and engaging historical novel from Acre books.

—

Of course a novel is more about structure than it is about plot. I know that now, though I didn’t when I began writing about Horace Wells, a dentist who lived in the 1840s and who discovered that laughing gas could take away pain–even during surgery. My novel’s plot, I knew, would be Horace’s brief and tragic life. But structure? Point of view decisions, where the story begins, where it ends, how time works? All that came in accidental chunks, typing blindly forward, hitting walls, retreating, picking up those pieces and moving them somewhere, maybe cutting them altogether. One of the great joys of writing this novel was that exploring, testing possibility, pushing in any direction that felt momentarily right – even if later the direction showed itself to be wrong. Below is a wrong: an excerpt that won’t appear in The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist. It’s an experiment in voice, me trying to find my way into the novel’s language of suffering.

Outtake 1:

Where does it hurt?

Can you describe the pain?

How it makes a limp of your walk, tilts you against the wall, lifts your face to the sun, blinds you to the child who wriggles in your lap, frustrates you so you kick at the spaniel underfoot, bark at your husband, crave an axe and a head to split with it. Maybe your own.

Where does it hurt? On every plowed acre and across every sand dune, under canopies of budding leaves and across tallgrass valleys, in the cellars under counting houses and in the soldiers’ camp, and beneath the stone bridge where crows and rats dance over unrecognizable bones. In your knees when you sit, in your back when you sprint, in your fingers as you knit, in your jaw when you chew, in your heart when you laugh.

But Horace Wells made pain go away.

—

He did make the pain go away, God bless him, for many people. But I read this bit and realized it was a guide, a summary of what the whole book should do. That pain described here? It needed to be salted through the novel: a sprinkle here, a sprinkle there. When I cut it, I felt no pain, because I’d written it again on other pages, in many scenes.

This next cut, though? The amputation hurt. I loved this ending. The book had always been a love story involving Horace and his wife, Elizabeth. She outlived him in life, and she does in this book, and so in this excerpt, I ended with her. The survivor.

Why cut it? Because Horace is still the main character. Because he loved Elizabeth and Elizabeth loved him. The book couldn’t end with her alone. The ending needed the two of them–together–even though history tells us that when Horace died Elizabeth was hundreds of miles away. But that’s a fact of history. It’s plot. Structure mattered more, and ultimately I used structure to fix that problem.

Then I cut the ending that I loved, and which waits here, below. I’m grateful to American Short Fiction for helping me reclaim it and share it with you.

Outtake 2:

When Elizabeth Wells was old, her once-sorcerous eyes now wet with senescence, and her son Charley grown into a pudgy and dapper middle age, he began to ask about his father. This he had never done prior, but he anticipated his mother’s death and understood that anything he wanted to know, he needed to learn now. “There is nothing I want to tell,” she answered. But one morning in early July of 1889, when he asked yet again about his father, she nodded, hands a-tremble as she touched tea cup to lip, a bit spilling onto the white table cloth.

She did not answer his question. Instead, she told him about a time when she was a girl, only nine, and the Connecticut River’s spring flood rose beyond routine and into memory. This was a year in which thick winter ice had cracked, floated and jammed; snowmelt rushed from streams in the Green Mountains; rainstorms with July’s warmth fell instead in March. Because she had forgotten much, Elizabeth left out many details as she recalled the flood for Charley. But it is true that the river obliterated its oxbows, wrecked bridges, stole unmoored oar boats, spread nearly a mile across low plains, whirled in pools and lurched in unpredictable eddies. In Windsor, half a dozen tobacco-drying sheds broke apart and vanished. A surveyor in Wethersfield waded into water at the town’s center and measured a depth of four feet, three inches. River towns emptied–from Enfield in the north to Old Saybrook in the south. Five people died, among them a recluse who lived so secretive a life on Wright’s Island that no one knew to miss him.

The waters receded almost as fast as they’d come, and what was heartache and devastation for men and women was for children a call to adventure. Elizabeth got away from her aunt one morning and hurried to the North Meadows, wanting to find a spot where her family had oftentimes picnicked, where she had made friends in a nine-year-old’s way with a grandfather oak. She knew the direction, picked her way as best she could, the ground sucking at her boots, the muddy hem of her dress catching on sharp grasses. Above, the sky glared, a whiteness, pale as bone. The land smelled black and murky, like a secret Elizabeth was not yet supposed to know. Mud that remained after the river’s retreat had left a brown mess of everything, even high up tree trunks. She felt a bramble of fear scratch her heart, but it mixed with an explorer’s charge at being first into a place, at being the one to name what might be discovered there.

Hatchet, the handle half buried in muck.

Broken plate with a blue pattern.

Spool of yarn, the color of silt.

Spine of a butchered pig.

Every step forward was a step over something. To balance, she grabbed twiggy branches of shad bush or elderberry, and when she pushed through a thicket the stems flicked her with mud. Because everything was brown, it was easy for her to imagine that behind each copse lurked child-eating monsters who usually lived along the river bottom but had been left behind, bewildered and angry, when the river moved on.

She came to a spot that looked familiar, that oak there, on the river bank just beyond a lowland of green-black muck. That morass paralleled the river, and it was too long to go around. But it was narrow. Determined to cross, she started in.

The mud grabbed at her boots. Horseflies pestered her ears and nose, ignoring how she slapped at them. Five steps forward and she tried to turn around, but her back foot stuck and pitched her forward. Arms out to catch herself, her hands splashed into the blackness and kept sinking–up to her shoulders. When she twisted to look whether someone might be coming to help, she only sunk deeper.

Now her aunt would be very angry. Elizabeth’s dress would never get clean. She imagined having to wear it for church so everyone would know she’d been bad.

Hoping to swim through the mud she kicked and stroked but sank deeper. She prayed so that His eye might be drawn to her. With great effort, she turned to face the way she’d come. No one there. Not even a monster. The dress would never get clean.

Trapped in that flood-muck of the meadows, she cried, believing she would die. She cried and cried. But of course she didn’t die. Eventually, crying bored her. Then, rather than kick and struggle, she reached an arm forward and waited. The mud shifted around her, but she didn’t sink. She moved again, with caution, as though at ease, waited, and somehow body and mud found an equilibrium. She never understood how. Again she moved a leg, waited. An arm. Shrugged her shoulder forward. Waited. Waited. All that long day, she pulled herself free.

Michael Downs is the author of The Greatest Show: Stories (LSU Press, 2012) and House of Good Hope: A Promise for a Broken City (University of Nebraska Press, 2007), which won the River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Prize. His debut novel, The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist (Acre Books, 2018) tells the story of the 19th-century man widely credited with discovering painless surgery. Downs is the recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives and writes in Baltimore.