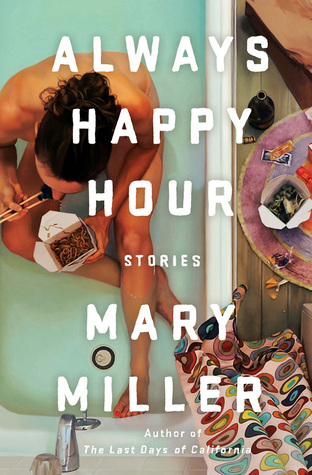

Always Happy Hour, Mary Miller’s second collection of stories, opens with the strangest dedication I have ever read: “For my exes.” Why would one dedicate anything to one’s exes? And not just one ex–not, say, “The One I’m Still Friends With”–but all of them, wholesale? At once blunt and tender, impersonal and twistedly sweet, these three words set a tone for the sixteen stories that follow. Exes–the crowd, the mob, the mass–preoccupy Miller’s aimless heroines. They trail behind the narrative present of each story, breadcrumbs leading back to some elusive moment when everything went screwy.

Always Happy Hour, Mary Miller’s second collection of stories, opens with the strangest dedication I have ever read: “For my exes.” Why would one dedicate anything to one’s exes? And not just one ex–not, say, “The One I’m Still Friends With”–but all of them, wholesale? At once blunt and tender, impersonal and twistedly sweet, these three words set a tone for the sixteen stories that follow. Exes–the crowd, the mob, the mass–preoccupy Miller’s aimless heroines. They trail behind the narrative present of each story, breadcrumbs leading back to some elusive moment when everything went screwy.

This is Miller’s third book. In her second, the novel The Last Days of California, a teenager joins her evangelical family on a soul-saving road trip in anticipation of the Last Judgment. Always Happy Hour returns to the subject matter of Miller’s debut story collection, Big World: jaded, self-effacing young women stumbling through love and sex. One worries that a boyfriend who films her fellating him will post the videos online; another travels across Mississippi with her boyfriend to photograph a woman in connection to a potential murder. They are grad students, writers, caretakers at foster homes. Some have ex-husbands they call up from time to time. All know from experience “how quickly life can rearrange itself into unfamiliar and unpleasant patterns.”

Miller specializes in the sad, almost wretched self-analysis that winds up to a satisfying punchline. “I miss my ex-boyfriend,” muses one protagonist, “. . . but there are so many of them now and I’m not sure which one I miss. Lately I’m running one behind so I only stop missing the last one when the current becomes the ex and then I miss him so I’m never fully with the one I’m with, which is maybe why they keep leaving me.”

We are mostly spared the breakups. Miller prefers to pause at the moment in a relationship when the alarm bells are just approaching a frequency at which alcohol and TV and still-good sex can no longer fuzz them out. The collection’s title (drawn from a story originally published in American Short Fiction) suggests a realm of boozy limbo, past the introductions but before the night tilts into ugliness.

Miller is unabashed to call the things we use, watch, and stuff our faces with by their proper names; her characters’ lives are strewn with pop-culture ephemera. A couple watches the forgettable Cameron Diaz flick The Box and has the exact conversation that movie was made to provoke (“Would you push the button?”). In “Love Apples,” a story that crosses Lorrie Moore at her zaniest with Mary Gaitskill at her filthiest, we are treated to what must be half the items on Taco Bell’s late-night menu. Miller is as candid about money as she is about Meximelts. The story “First Class” follows the shifted dynamic between two friends, one of whom won millions in the lottery. (“This was the only thing I knew for sure about rich people: once the money was yours, it didn’t matter that you hadn’t earned it, had done nothing to deserve it; it didn’t matter where it came from.”) In “Hamilton Pool,” a cash-strapped couple rations out the last of their condoms and cigarettes with a sense of apocalyptic dread.

Nothing much happens in these stories; in fact, they are studies in inertia and ambivalence. But Miller’s frank, full-hearted voice and disarming humor keep the ride fresh even if you’ve known the landscape your whole life.

Charles Ramsay McCrory is the Editorial Fellow for American Short Fiction. He holds a B.A. in English from The University of Mississippi. His work has received the 2015 Mississippi Review Prize for fiction and is published or forthcoming in Southern Humanities Review, Gargoyle Magazine, and The Cossack Review.