1. _

On the morning of Friday, March 19th, 1971, Hunter S. Thompson, already the bestselling author of one book and long overdue on his contract for another, accepted what appeared to be a fairly innocuous journalistic assignment: write five hundred words of copy for Sports Illustrated to go along with a photo essay on the Mint 400 motorcycle race, which was scheduled to take place that coming weekend in Las Vegas 1.

It was a cushy offer, to say the least: Thompson would get paid three hundred dollars in advance, and the magazine would also cover the hotel and travel expenses.

At the time he was down in Los Angeles finishing up an investigative piece for Rolling Stone about the death of Ruben Salazar, a well-known Mexican-American journalist who’d been killed, in a way that seemed far from accidental, by members of the L.A. County Sheriff’s department.

Salazar had been a prominent critic of the local police, and the previous August, after covering a protest-turned-riot for the television station KMEX, he was having a beer with a colleague on Whittier Avenue when deputies, acting on what they claimed was an anonymous tip, sealed off the premises and fired high-powered canisters of tear gas through the front door, one of which struck Salazar in the head. He died instantly.

It was the most complex story Thompson had ever attempted to write. Part of the difficulty had to do with the technical details—contradictory versions of what, exactly, happened that August afternoon—but Thompson was also struggling to understand the broader socioeconomic context of the Los Angeles barrio: the relationship between a domineering local government and the minority community it had ruthlessly policed for decades.

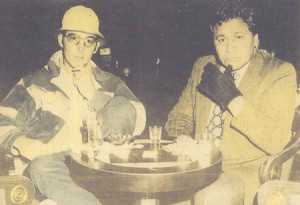

His main source on all of this was the attorney and writer Oscar Zeta Acosta, a trusted friend. Acosta had called Thompson the night Salazar was killed, setting the article in motion, and the reason Thompson had flown down to L.A. that March was to conduct a final round of reporting; Rolling Stone planned to run the finished piece that April. But on this latest trip the two barely had a chance to speak; in Acosta’s house and office they were often surrounded by radical members of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, who tended to see the national press as the propaganda wing of the authorities seeking to maintain the status quo, and Acosta understood that any cooperation with Thompson could be detrimental to his reputation as an activist.

So on a blue March morning in Southern California, Thompson, with his Rolling Stone article unfinished and nearing deadline, accepted Sports Illustrated’s offer to write a few hundred words—but with an ulterior motive in mind: he invited Acosta to come along too, knowing that they’d finally have the chance to speak freely.

Acosta jumped at the invite—like Thompson, he wasn’t the sort to refuse a free trip to Las Vegas—and the next day, in a rented Chevrolet convertible, they took the Hollywood Freeway out of Los Angeles, passing Santa Anita and San Bernardino before bearing north at the Cajon Pass, where the San Gabriel mountains fell away and Interstate 15, completed only two years earlier, cut like a waterless canal through the repeating basins and ranges of the Mojave Desert.

At last they could talk. And throughout that Saturday, as their conversation continued and Las Vegas came alive in the cool arid night, they drank and gambled and went over every aspect of the Salazar case—its broader context.

Alcohol wasn’t the only substance they had at their disposal, of course. But while they’d brought along additional drugs of their own, the actual inventory was a bit different than you might think. In his possession Thompson had Dexedrine—a version of the psychostimulant amphetamine he’d been taking regularly for years, in pill form, and that’s still prescribed today for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder—and Acosta brought a large amount of marijuana: a severe legal risk, especially in Nevada. That was it; for this trip, they didn’t have psychedelic substances like mescaline or LSD 2.

In Las Vegas that weekend Debbie Reynolds was playing at the Desert Inn. Sonny and Cher debuted at the Sahara. Across the continent, at Fort Benning, Georgia, U.S. Army Lieutenant William Calley was being court-martialed for his role in the My Lai massacre. Back in Los Angeles, the jurors in the Manson trial had begun deliberating; in nine days they’d return with guilty verdicts on all counts. And more than fourteen months were still to pass until five men, acting on instructions from Nixon officials E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, would be caught breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington DC.

Thompson was thirty-three years old. He’d been married for seven years and was living in Woody Creek, Colorado, with his wife Sandy and son Juan 3. Acosta was about to turn thirty-six. Together they stayed out the entire night, and the next morning—Sunday, March 21st—Thompson drove fifteen miles north, in the direction of Floyd Lamb State Park, where, on the grounds of what was known then as the Mint Gun Club, the motorcycle race was scheduled to begin.

The bikers set off just after dawn. Pretty soon it became clear that there wasn’t all that much to report; on account of the dirt track and the staggered nature of the race, an enormous cloud of dust soon descended on everything, limiting visibility, and instead, Thompson retreated to the makeshift press room, where he chatted with Life magazine’s West Coast bureau chief and began arranging his notes from the night before. His immediate goal was to draft the captions, but he quickly blew past SI’s word limit, using the narrative of the race as a springboard to explore, in an essayistic fashion, the history of gambling and the origins of Las Vegas itself 4.

That evening Acosta took the late flight back to Los Angeles—he needed to be in court first thing Monday morning—and in Thompson’s care he left behind a pair of items too risky to chance through airport security: the remaining marijuana and a loaded .357 magnum handgun.

Thompson, confronted with both in the solitude of his hotel room, was suddenly hit by an extreme bout of panic. This was partially the result of having been been awake for so many hours on Dexedrine, a drug that’s known to cause paranoia and anxiety when taken at a regular dosage. Another part was reality itself; getting caught with either the marijuana or the gun could easily lead to serious jail time. In addition, he was beginning to understand just how dire his own financial situation had become; recently he’d incurred a substantial debt with American Express, and the charges for this current trip could cause him to lose his card altogether, even if Sports Illustrated eventually reimbursed him—an increasingly unlikely prospect, considering the hundreds of dollars he and Acosta had already run up 5.

His plan was to try and flee the hotel in the morning and let the representatives of the magazine, who’d booked the room, sort out the bill. He’d decided to leave at dawn. In the meantime, he started writing; using the Mint Hotel stationary, he described exactly how he was feeling—the nature of his panic, its overwhelming crush.

It was a terrifying, exhilarating experience. The previous week, during his struggle with the Salazar case, he’d gotten stuck trying to describe the shape of something he couldn’t yet see. And now, face-to-face with a raging, honest-to-God Dexedrine-fueled anxiety attack, the object of his articulation appeared as lucid as the paper on which he inscribed the words. For once he could perceive exactly what he needed to say. Context and chronology were secondary. Instead, he forged the precision he was looking for by depicting the nature of the emotion at hand, and in this sense, the notes he made became a way to circle the heft of the thing he felt, a movement on the page that mirrored his own vortical logic.

Later that morning, after departing the hotel without incident, he found that, to his surprise, he still couldn’t stop writing; all along Interstate 15, at rest areas, gas stations, and run-down local bars he continued to articulate the reality of his experience, its vividness.

He’d written personal narrative before, most notably about a trip to the Kentucky Derby—an impressionistic style of composition he’d started referring to as “Gonzo.” But in the past there’d always been a deadline, the desperation to meet it; he’d taken his notes and transcribed them directly because he’d run out of time to craft the material into a larger whole.

This instance was different. The structure wasn’t journalistic. Instead, the immediacy of the composition became a necessary part of the story, both its form and function. “What I was trying to get at in this was [the] mind-warp photo technique of instant journalism,” he’d write to Tom Wolfe three weeks later. “One draft, written on the spot at top-speed and basically unrevised, edited, chopped, larded, etc. for publication.” It was, in his opinion, the best way to recreate the truly subjective nature of reportage: a perspective he believed to be diminished by the subsequent editorial process, which emphasized objectivity.

Back in Los Angeles—buoyed by the anonymity that only a very large city could offer—his panic subsided. He finally had what he needed to complete the Salazar story, and with his Dexedrine, notes, and typewriter he checked into a crowded two-story motel just across from the Santa Anita racetrack, where the spring thoroughbred season happened to be in full swing.

“The rooms all around me were jammed with people I couldn’t quite believe,” he’d later write 6. “Heavy track buffs, horse trainers, ranch owners, jockeys & their women . . . I was lost in that swarm, sleeping most of each day and writing all night on the Salazar article. But each night, around dawn, I would knock off the Salazar work and spend an hour or so, cooling out, by letting my head unwind and my fingers run wild on the big black Selectric . . . jotting down notes about the weird trip to Vegas.”

And this is where the story nearly ended, at least in regards to the “weird trip” he and Acosta had just completed: as a pile of impressionistic, handwritten notes typed up in the predawn darkness of a Santa Anita racing season that was rapidly drawing to a close. In other words: he knew he had something on his hands. He just didn’t yet know what.

2. _

Hunter Thompson finished the Ruben Salazar piece in early April. Titled “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” and running nearly 20,000 words, it was published at the end of the month, the longest article Rolling Stone had yet put out.

He’d reached the conclusion that Salazar’s death had been accidental—a result of the brutal, indiscriminate police tactics for which the Sheriff’s department still refused to apologize—as opposed to a targeted assassination, which he deemed L.A. law enforcement far too incompetent, short-sighted, and corrupt to possibly pull off.

He also typed up and sent his caption copy to Sports Illustrated—two thousand words more than they’d initially requested. It was, in his telling, “aggressively rejected.”

But he ignored their requests for revisions. Instead, after typing up his notes from the trip—the historical, personal, and imagined digressions that had poured out of him at various moments in Nevada and the surrounding desert—he noticed a larger narrative binding everything together: the story of the trip itself, which he’d begun to tell with the exaggerated, scenic immediacy of a crime novel or road narrative. Already he had ten thousand words, and with encouragement from Jann Wenner and the editors from Rolling Stone, he was hoping to keep going.

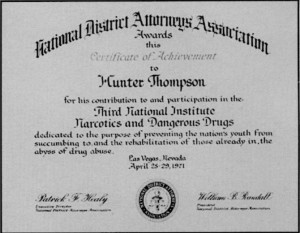

But as April wore on, he felt his momentum waning, and he was looking for a way to recreate the rush that had set in motion the initial pages when, by chance, the perfect opportunity presented itself: in his mail he discovered an invitation to attend The National District Attorneys’ Association’s Third National Institute on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (it’d been sent his way, no doubt, on account of his campaign the year before to become sheriff of Aspen), which was scheduled to take place April 25th-29th at the Dunes Hotel. Rolling Stone agreed to let him cover it—and to put him up at the Tropicana, in the heart of The Strip. Oscar Zeta Acosta would join him again. And so, just thirty-five days after his initial trip to Vegas, he took a Sunday flight back to Nevada to participate in the conference.

By now he was starting to realize that he might have something more substantial on his hands than just another magazine article. Three years earlier, Thompson had signed a book deal with Jim Silberman, his editor at Random House, to write about “The Death of the American Dream.” He’d done so in a rush—in the wake of the success of his first book, Hell’s Angels, which by 1968 had already sold nearly half-a-million copies, an astonishing amount—and the enormity of the new subject matter weighed on him. He missed his contractual deadline, unable to find the right narrative, and by the start of 1971, facing the prospect of defaulting on the deal altogether, he’d grown desperate—hoping instead to cobble together a collection of his recent freelance articles. In this sense, the dramatization of his March trip for Sports Illustrated couldn’t have come at a better time; when he checked out of the Santa Anita motel at the end of March, Thompson had the opening of a story that addressed the subject of the project he’d struggled with for years. Suddenly Las Vegas itself could represent everything he’d been trying to say, and by depicting the city’s excesses in an imagistic sense, he saw the chance to concretize the abstract thematic content he’d been after 7.

So when Acosta and Thompson reunited that last week of April in Las Vegas for the District Attorneys’ conference, part of the plan was to act out the direction in which he wanted the story to go: they’d search for the American Dream themselves, discussing it with whoever crossed their paths. It was a strikingly self-aware attempt; they meant to bend reality—or their version of it—toward the truth the book would depict.

This wasn’t the only difference from the March trip; this time, Thompson recorded meticulous audio notes (nearly three hours of which were made available in 2008 via the box set The Gonzo Tapes).

Once again, he and Acosta appear to have brought marijuana and Dexedrine—of which Thompson had about a dozen capsules left—as well as Benzedrine pills, a harsher version of amphetamine, and also a single red Seconal, a barbiturate used to treat insomnia 8. They still didn’t have any mescaline or LSD.

They upgraded their previous fifteen-dollar-a-day Chevrolet rental, opting instead for a top-of-the-line Cadillac convertible 9. Together they did spend some time at the actual conference, but for the most part they found the whole thing unbearable: the other attendees were so out of touch that there wasn’t much work left to do in terms of parody or indictment. Besides, it was clear from the beginning that any hope of attending the event “undercover,” which had been the initial plan, could never work; there was no way to hide in such a uniform crowd of buzz-cut, straight-laced law-enforcement personnel, despite their attempts to dress respectfully. And Acosta, bristling at the casual bigotry of the attendees—“People mistake me for a bellboy and they want me to take their baggage for them,” he can be heard remarking on the tapes, “I get tired of that shit!”—took to strolling around the Dunes in a yellow fishnet top, within which he tucked a very large hunting knife, so that should anyone questioned him on just what he thought he was doing, he could claim with perfect certainty that the weapon was legal; the revealing nature of his shirt meant that the knife wasn’t technically concealed.

All in all, they seemed to spend the majority of the trip taking amphetamine and driving around 10. Throughout Las Vegas and its surrounding towns they kept stopping to interview people; in an eerily self-aware tone, both Thompson and Acosta asked again and again about the location of the American Dream—where it might be found.

On Thursday, Acosta, who hadn’t enjoyed this trip nearly as much as the previous one, returned early to Los Angeles, and Thompson, sleepless and alone again, drove out to Lake Mead, about thirty miles east of the city 11. Experiencing the sort of paranoia that’s to be expected after four days of heavy drinking and Dexedrine, he became convinced he was being followed. Every car looked like a cop’s. Later, he accidentally crossed into Arizona and was startled, as if in a dream, by the strangeness of a sign along the road—a warning to motorists to watch for mountain sheep.

That night—Thursday, April 29th—he returned to his suite at the Tropicana and, in a state of absolute exhaustion, recorded his final notes; the next day he flew back to Colorado.

And like that the most important part was over. For better or worse, Thompson had everything he needed to arrange the larger shape of the narrative he’d been working toward, in person and on paper, throughout the previous month. Now, at his home back in Woody Creek, he spent the summer writing and revising it. In May Rolling Stone decided to make him a “national correspondent,” a salaried position that meant, for the first time, he’d be receiving a regular paycheck. There was talk of new assignments: that fall, he might cover the war in Vietnam—or perhaps he’d work on the domestic front, joining the campaign trail for the upcoming presidential election. But first he needed to finish “The Vegas Book,” as he called it. To do so, he found himself imposing what he’d later describe as “an essentially fictional framework” on the notes that had set everything in motion 12. With the help of his editors at Rolling Stone, large sections were cut. He combined the two trips, which initially occurred more than a month apart, into a single, weeklong narrative. Certain events were exaggerated, other invented whole cloth, and in the end he imbued the perspective of the narrator—Raoul Duke, Thompson’s preferred alias in real-life—with such drug-induced subjectivity, it can be difficult at times to know for sure whether the events on the page are actually occurring or simply being imagined.

The final version would clock in at 204 pages (more than sixty thousand words)—over the course of which Thompson would manage to include a grand total of twenty-two psychopharmacological substances 13. Acid/LSD appears the most: it’s mentioned thirty-nine times and is consumed, in scene, twice 14. Mescaline comes in second, referred to on nineteen different occasions, but regarding consumption it takes top billing: Raoul Duke and his attorney are depicted ingesting it no less than ten separate instances (five each).

In contrast, Thompson would refer to amphetamine by name only three times—and always in conjunction with the phrase “psychosis”—and while eight additional references to both “uppers” and “speed” can be found throughout, neither Dexedrine nor Benzedrine is specifically mentioned 15 16. In fact, Thompson never once dramatizes the ingestion of psychostimulants on the page, even though he was taking them continuously throughout the two real-life trips—and despite the fact that, upon a closer read of the book itself, the narrator Raoul Duke appears to be consuming it constantly 17. I’d actually go so far as to argue that the narrator of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is never not on amphetamine; out of all the substances in the narrative, it’s consumed with the highest quantity and most regularity.

Which brings us to our larger point, one we’ve been working toward since the start: while Hunter Thompson would manage to include in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a wide variety of subjects, one theme we tend to overlook, today, is a perspective on drugs that manages to articulate, with surprising foresight, our own present-day relationship with psychopharmacology—with stimulants, especially.

After all, Thompson wasn’t taking Dexedrine to get high, to expand his consciousness; his amphetamine use could be egregious, yes, and on these two trips, after so many days of constant consumption—of drinking and not sleeping—the end result, the general degradation of his physical and mental state, would seem to suggest otherwise. But he didn’t use the drug to escape the reality of the world around him, in the way he tended to with psychedelics 18.

Under ideal conditions, the effects of a stimulant, as opposed to those of mescaline or acid, will mimic sobriety; reality appears less blurry, more immediate, and as a result, you can complete the task at hand without freaking out about how difficult and burdensome said task has become. And while Thompson did all sorts of journalistic work on Dexedrine—reporting, interviewing, composing, and revising—what matters is that, for the most part, his relationship with this drug was astonishingly similar to the one millions of Americans currently strike when, with or without a prescription, they take Adderall or Ritalin or Vyvanse: the most common goal is functionality.

Of course he would push the limits of this functionality further than most, and don’t get me wrong: this isn’t to say that he should be retroactively diagnosed with the sort of condition stimulants are prescribed for today or that he was consciously self-medicating or anything like that. But on some level, he had to know that the whole thing amounted to a bargain—a zero-sum equation, as in: whenever something is taken something is also lost. Dexedrine might allow him to succeed at his profession in a way he never may have managed, without it, but if we’ve learned anything from the two trips on which Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is based, it’s that he understood better than most the crash lying in wait—that the breakdown wasn’t simply inevitable; it was the currency on which the trade he was making depended.

3. _

Hunter Thompson finished the final draft of his Vegas book in the fall of 1971. That November it was published in Rolling Stone, in two installments, under the subtitle A Savage Journey into the Heart of the American Dream. The British artist Ralph Steadman, who’d never been to Las Vegas himself, provided the artwork. Raoul Duke was officially listed as the author.

But at Random House, which planned to release a hardcover in the summer, Jim Silberman insisted that Thompson use his own name. This led, naturally enough, to a discussion on genre, and eventually the issue came to a head; that spring the New York Times needed know if the book would go on their fiction or nonfiction list—if it would be categorized as journalism or a novel.

The solution? Thompson and Silberman decided on a separate category altogether: Sociology.

Today this feels surprisingly accurate—and also a bit silly, if only in a literary sense. And while the question of truth has remained just as controversial as it was forty-five years ago, perhaps we can all agree that one of the clearest benefits of our continued discussion on the topic has been the creation of a whole new set of terms with which to argue. Is Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas best characterized as a nonfiction novel? Or an experimental essay? Autofiction? Something else entirely?

The fact that we’re asking the question at least implies that we’ve become more comfortable with works of a hybrid nature—which is a good thing, in my opinion.

Not that the issue at hand is strictly a modern one, to be sure—we’ve always been aware of the various ways in which, across time, we’ve assigned works of art to genres that eventually come to feel outmoded—and perhaps what we’re really talking about has more to do with perspective: specifically, the imagined kind we all sometimes can’t help indulging.

Myself included. Let me explain: just last month I was driving from Las Vegas to Los Angeles—stuck in terrible Sunday traffic at the California state line—when I was suddenly overcome by the sort of the distanced, hypothetical, entirely figurative point of view I’ve experienced on certain occasions before: what would it be like to read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas from a remove—from a point in the incredibly distant future, perhaps?

For comparison I started thinking of the story of Trimalchio—a character in Petronius’s first-century Roman masterpiece The Satyricon—or to be specific, the setting of that story: its banquets and slaves and ostentatious estates, all of it expressed without inhibition in the stunningly musical Latin of its time.

And at that moment I couldn’t help but picture 1971 Las Vegas as it might look a few thousand years from now: not the physical remnants—which, if there’s any architectural justice in the universe, will be long since sunk to the bottom of the Great Basin—but Thompson’s version of it, recorded for posterity in the book he felt so strangely compelled to write. Ancient drugs and a ruinous desert city: Is that how it might someday appear? And considering the content and style in which both the subject and setting are expressed, it’s fair to say that the future reader will at the very least be left with a vivid a portrait, rendered with startling clarity by a journalist of the time—someone who’s arguing against the flaws in his society while also, as a means to develop this argument, engaging in the general dissolution around him.

After all, if I were a 40th century reader hoping for some insight into the “1960s,” what better place to look? With Fear and Loathing, you get a deeper sense of that time and place than from something by Joan Didion or Tom Wolfe—both of whose perspectives are fine in their own right, just not nearly as radiant, argumentatively and dramatically, as Thompson’s. At least in my opinion. But then, that’s the problem; even contemporary writing is up to its neck in its unbearably narcissistic conception of its primacy 19.

Still, I’m being completely honest when I tell you, now, that I believe Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas has a shot to endure—transcribed and translated again and again in the way a technology like writing has always allowed—long after the rest of the physical world from this time and place is gone.

In other words: there exists the possibility, however slim, that this book, for the most part set within the hedonistic enclave of the twentieth century’s most powerful nation-state, will someday serve as a testimony of the moment when, for the very first time in its history, humankind enjoyed enough stability and scientific advancement to reach into its own consciousness and, with a few quick jots of the proverbial fingers, employ an absurdly specialized tool—lab-manufactured psychotropic substances—to rearrange the most remote processes of the human brain, that signature through which we see the world, as good a locale for identity as any.

As Thompson himself suggests, the fatal flaw of this revolution was simple enough: the belief that such rearrangement was inherently beneficial—that the ability to alter consciousness is always a productive endeavor 20.

The brain, after all, is probably the only true paradox left: something too complex to perceive its own complexity; and if Fear and Loathing will still be available to some future readers two thousand years down the road, what may very well remain applicable, thematically—outshining concepts like the “American Dream” and consumerism and North American post-war political hypocrisy—is the entirely human hope that change on a personal level (in this case the most personal of all) is inherently a good thing. Even when it’s not.

All of which is to say: the psychopharmacological revolution is the unstated theme of Thompson’s book, a claim I’m comfortable enough making, since any good artistic argument must exist beyond the overt aim of the text itself. We readers have to do the work to figure out what’s really in play.

If two millennia from now, as a species, we’re not long since submerged or exploded or entombed under some tideless rock—if somehow we’re still reading works from the past in the way that we do currently—then please consider this a personal wager that a future version of us will eventually take an interest in Fear and Loathing for its early and unremittingly unique perspective on psychopharmacology, a theme that manages to grant the book, despite its flaws, something similar enough to what we typically refer to as genius.

If I’m completely off base; if the future of humanity is, in fact, destined to worship at the feet of something along the lines of a bronzed Joan Didion statue twelve times the size of God; if Fear and Loathing will instead be interpreted as an overwhelmingly meretricious work of art—then there’s always this final audio note of Thompson’s to keep in mind, at least when it comes to the process through which anything that lasts is initially composed:

Las Vegas, April 29th, Thursday night [. . .] And now I have to figure out what the fuck to do with the story [. . .] I’m very tired, My lips are dry and my mouth feels like concrete. It’s no good, this lack of sleep, constant drink, no sleep, Benny pills, you wonder sometimes what the hell it’s gonna lead to. Here I am covering this narcotics and dangerous drugs conference so drugged up and crazy that I should be put in a rest home, if not the jail. But I’ve done nothing—I’m innocent. I have no guilt. That’s a good note to close on, I suppose, no guilt. . . But what do you call it? What is it? What’s the word? 21

Timothy Denevi is the author of Hyper, which is now available in paperback from Simon & Schuster. His work has recently appeared in The Normal School and Gulf Coast, and online in The Atlantic and Time. He’s an assistant professor in the MFA program at George Mason University, where he teaches nonfiction. He lives near Washington D.C. with his wife and two children. His first essay on Hunter S. Thompson for American Short Fiction can be found here.

Timothy Denevi is the author of Hyper, which is now available in paperback from Simon & Schuster. His work has recently appeared in The Normal School and Gulf Coast, and online in The Atlantic and Time. He’s an assistant professor in the MFA program at George Mason University, where he teaches nonfiction. He lives near Washington D.C. with his wife and two children. His first essay on Hunter S. Thompson for American Short Fiction can be found here.

NOTES:

1. Five hundred words: Thompson refers to this specific word count in an April 22nd letter to Tom Vanderschmidt, the editor at Sports Illustrated who contacted him about the assignment.

2. They hadn’t been able to acquire psychedelic substances: Two months after this trip, Jim Silberman, Thompson’s editor at Random House, wrote in a letter: “You know it was absolutely clear to me reading Las Vegas 1 [what was to become the first half of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas] that you were not on drugs,” to which Thompson wrote back: “This is true,” and went on to explain that the account of the first part of the trip “was a very conscious attempt to simulate a drug freakout—which is always difficult, but reading it over I still find it depressingly close to the truth I was trying to recreate.” By “drugs” they both seem to be talking about psychedelics, as opposed to the Dexedrine capsules Thompson consumed regularly, and later in this same letter Thompson explains that after the trips to Vegas, he and a friend “ate a bunch of mescaline and went to a violent, super-jangled car race,” where they “experienced the same kind of bemused confusion with the reality that Raoul Duke & his attorney had to cope with in Vegas.” He ends by asking Silberman to keep his opinions of Thompson’s “drug diet” that weekend to himself; “As I noted, the nature (& specifics) of the piece has already fooled the editors of Rolling Stone. They’re absolutely convinced, on the basis of what they’ve read, that I spent my expense money on drugs and went out to Las Vegas for a ranking freakout.”

In interviews over the subsequent decades, Thompson would contradict himself—he later claimed that everything he wrote in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was true—but this letter to Silberman, coupled with comments from the audio tapes he made during his April return to Vegas for District Attorneys’ convention on narcotics and dangerous drugs (see: Acosta hadn’t enjoyed this trip, below), suggests that they really did only bring Dexedrine and marijuana. The context makes sense, too, considering the impromptu nature of their trip and/or the general difficulty of obtaining these substances at the last minute. For more, see pages 375-444 in Douglas Brinkley’s second collection of Thompson’s letters, Fear and Loathing in America, as well as The Gonzo Tapes, discs two and three.

3. And son: At the time Juan was six. The Tuesday after Thompson returned to Los Angeles and checked into the Santa Anita hotel to begin his sleep-all-day write-all-night schedule—March, 22nd—was, in fact, Juan’s seventh birthday.

4. SI’s word limit: That summer, in a letter to Mark Penzer at True magazine, Thompson tried to sell the now-3500-word version of the captions that Sports Illustrated rejected: “A friend of mine at SI sent me out there as a sort of lark, with no real assignment except to come back with a caption to justify expenses . . . but for reasons of my own I wrote a much longer & dirtier thing than they wanted. (I write excellent captions, but it struck me that a scene like that deserved a bit more. . . ).”

5. Hundreds of dollars: Nearly five hundred dollars, in fact—and SI never would reimburse him; as a result American Express would indeed cancel his card—a disastrous development for a freelance journalist in 1971. Eventually, as part of the deal to acquire Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Jim Silberman at Random House would agree to pay the expenses for this trip and the one in April, which when all was said and done, amounted to nearly fifteen hundred dollars—or about nine thousand dollars by today’s standards.

6. He’d later write: This quote about the Santa Anita racing season is from the essay “Jacket Copy for Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas,” which was composed in the fall of 1971 but wasn’t published until the release of The Great Shark Hunt, in 1979.

7. The abstract thematic content: Personally, my favorite example of this is from page 57 of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas:

Who are these people? These faces! Where do they come from? They look like caricatures of used-car dealers from Dallas. But they’re real. And, sweet Jesus, there are a hell of a lot of them—still screaming around these desert-city crap tables at four-thirty on a Sunday morning. Still humping the American Dream, that vision of the Big Winner somehow emerging from the last-minute pre-dawn chaos of a stale Vegas casino.

Big Strike in Silver City. Beat the dealer and go home rich. Why not? I stopped at the Money Wheel and dropped a dollar on Thomas Jefferson—a two-dollar bill, the straight Freak ticket, thinking as always that some idle instinct bet might carry the whole thing off.

But no. Just another two bucks down the tube. You bastards!

No. Calm down. Learn to enjoy losing.

8. Marijuana and Dexedrine: Thompson and Acosta discuss their drug situation at length in these tapes—especially on the third track of the second disc, when, in the hotel room that Monday, they tally up how much Dexedrine and Benzedrine they have for the trip. At other moments they brainstorm about finding a way to purchase mescaline, which they clearly don’t have—going so far as to make a very awkward and unsuccessful phone call to someone they’ve never met—and they even speculate about (though never attempt) buying and inhaling ether, a substance with which Acosta appears completely unfamiliar.

9. They also upgraded: Afterward, Thompson, by way of an explanation to Silberman about the new round of expenses this second trip had incurred, would write: “The point is that you can’t send a man out in a fucking Pinto or a VW to seek out the American Dream in Las Vegas. You want to be able to come roaring into the Circus-Circus in a huge Coupe de Ville and know the insanity of watching people jump and run and salute and all that crap…which is crazy, of course, but the insane truth is that the difference between fifteen dollars a day for a Mustang and twenty dollars a day for a white Cadillac convertible is massive in LA or Las Vegas.”

10. The majority of the trip: You can find all this and more in his audio notes, the last of which describes, as Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” drones in the background, the terrible state of their suite at the Tropicana: “Puddles of rum, bourbon, Chivas Regal, Schweppes soda, beer cans everywhere, the box for the Sony radio, Oscar’s yellow net shirt, which I’ve inherited, somehow.”

11. Hadn’t enjoyed this trip: On the tapes Thompson would remark: “My attorney couldn’t handle this trip too well. The first half of this thing [what Thompson wrote about their March trip] was apparently a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. He became the monster I created in the first half. The second half he actually did all that stuff. Terrible smashing of lightbulbs in the hotel room. And the insane buying of hammers and coconuts and wooden bowls and just gross demented behavior. And stomping around with that terrible net shirt and the knife on his belt in the hotel. And staggering/lumbering into the conference the very few times he actually went into the meeting room. Usually he would sit by the door in a chair, staring at the crowd, while they were looking at the movie and also at him, and he had his back to the screen, just watching them [. . .] But he finally got so paranoid [. . .] whatever it was, some sort of racism—he finally just had to quit.”

12. An essentially fictional framework: This quote is also from “Jacket Copy.” In the same essay he goes on to say: “Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas will have to be chalked off as a frenzied experiment, a fine idea that went crazy about halfway through . . . a victim of its own conceptual schizophrenia, caught & finally crippled in that vain, academic limbo between ‘journalism’ & ‘fiction.’”

13. twenty-two psychopharmacological substances: These calculations, which are my own, were done using the 1998 Vintage Books edition of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—the paperback one with the image of a cyclonic Johnny Depp on the front cover—and in them I don’t include alcohol; mace, in contrast, does make the cut, due in no small part to this quote from page 61: “Shit, there’s nothing in the world like a Mace high—forty-five minutes on your knees with the dry heaves, gasping for breath. It’ll calm you right down.”

14. Acid/LSD appears the most: To clarify: twenty-nine times as “acid” and ten times as “LSD.” Mescaline, in contrast, is referred to eighteen times by that name. . . and once, on page 32, by what might be my favorite phrase in the entire book: “fiendish cactus juice.”

15. Would refer to Amphetamine by name only three times: On pages 75, 83, and 199.

16. Eight additional references: As “speed” on 100, 178, 202; as “uppers” on 4, 14, 165, 178, and 202.

17. Consuming it constantly: While the consumption of amphetamine is never dramatized in the pages of the book, the substance is present in Duke’s initial and subsequent psychopharmacological inventories—“[. . .] a whole galaxy of multi-colored uppers [. . .]” (4); “My attorney had eaten all the reds, but there was still quite a bit of speed left . . .” (100)—and when he does refer to it directly by name, it’s in regards to his ongoing experience with its adverse effects (“amphetamine psychosis,” 75), the extremity of which could really only exist if he’s been consuming the drug regularly since the beginning of the narrative. Finally, over the course of two hundred pages and a timeline spanning seven days, the narrator appears to fall asleep on only two occasions: once, at the Tropicana, during a moment told in flashback (181), and finally on the second-to-last page, during the flight to Denver from Las Vegas: “I was asleep when our plane hit the runway, but the jolt instantly brought me awake. I looked out the window and saw the Rocky Mountains. What the fuck was I doing here? I wondered. It made no sense at all” (203). This final scene on the airplane seems to represent, for a fleeting instant, the absence of all drugs, a state we might as well describe as sobriety. It lasts for seven paragraphs: the time it takes the narrator to find an airport pharmacy, procure a dozen amyls, and, in the book’s final line, recast himself as “a monster reincarnation of Horatio Alger . . . a Man on the Move, and just sick enough to be totally confident” (204).

18. In the way he tended to with psychedelics: As his first wife Sondi says on page 99 of the oral history of Thompson’s life, Gonzo: “I’ve had friends who used LSD to really explore things spiritually, but for me, and for Hunter too, it was really more of an escape”; see also, the following account of his first experience with LSD, in 1965: http://americanshortfiction.org/2015/08/07/things-american-ken-kesey-hunter-thompson-hells-angels-la-honda-august-7th-1965/

19.Contemporary writing is up to its neck: As Thompson points out on page 67 of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: “History is hard to know, because of all the hired bullshit.”

20. As Thompson himself suggests: On page 179 of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: “the desperate assumption that somebody—or at least some force—is tending that light at the end of the tunnel.”

21. What’s the word? This passage is from The Gonzo Tapes, disc 3, track 17, which is titled: “Vegas D.A. Final Notes . . . the Whole Room is Total Chaos: I Can’t Imagine How I’m Going to Get This Whole Fucking Room into One and a Half Suitcases.”

SOURCES & FURTHER READING:

- “Jacket Copy for Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas” and “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” The Great Shark Hunt, by Hunter Thompson, Simon & Schuster, 1979

- Fear and Loathing in America: The Gonzo Letters, Volume II, edited by Douglas Brinkley, Simon & Schuster, 2000

- “The 450-Mile Square Parking Lot,” by Hunter Thompson, Pageant, December, 1965

- Gonzo: The Life of Hunter Thompson, by Jann Wenner and Corey Seymour, Back Bay Books, 2007

- Outlaw Journalist, by William McKeen, Norton, 2008

- Hunter, E. Jean Carroll, Dutton, 1993

- Fear and Loathing, by Paul Perry, Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1992

- When the Going Gets Weird, by Peter Whitmer, Hyperion, 1993

- “The City: In Search of Thompson’s Vegas,” by F. Andrew Taylor, The Las Vegas Sun, 1997

- Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone, edited by Jann S. Wenner, Simon & Schuster, 2011

- The Gonzo Tapes, Shout Factory, 2008

- Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, by Hunter Thompson, Ballantine, 1971

- “Interview with P.J. O’Rourke,” by P.J. O’Rourke, Rolling Stone, November 28, 1996

- “Hunter Thompson, The Art of Journalism No. 1,” by Douglas Brinkley and Terry McDonell, The Paris Review, Autumn 2000

- Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter Thompson, directed by Alex Gibney, Magnolia, 2008