This column introduces a new online series we are featuring here at American Short Fiction. ASF celebrates contemporary voices in fiction—in our print issues, a story by a preeminent writer might sit next to a story that represents its author’s very first publication—but all of our authors would quickly name past favorites who have influenced them, would agree that they follow behind a splendid parade of writers whose stories established one of the great American literary forms. This occasional series will feature a detailed look back at an American short story by an author who is no longer alive. Whenever possible, we will link to the relevant text, so that you can read along companionably beside us. Because yes, we spend our days happily reading brand-new stories, but just so you know, we read dead people, too.

We’re all familiar with the names that light up the great wandering way of American short fiction. No doubt this space will feature stories by many of them in the coming years. But I wanted to begin the series quietly, with a writer who, while important in his day, may be new to many readers, because I like the idea that this column will be a place of discovery, where unfamiliar corners of this literary country can be freshly explored. Fiction is a land with two frontiers—one before us and one behind us—and part of our privilege as readers is that, from the comforts of home, we might be pioneers in either direction.

As an editor at American Short Fiction, I repeatedly bump against the question of what makes a story American. In a country with a changing population, where the cultural touchstones (from breakfast tacos to Barack Obama) that help build our nation’s identity are beginning to feel foreign to some of its members, that question, posed more widely, seems to be prying away at our national consciousness, too. As this column goes to press, an immigration reform bill has ground to a halt in Washington as our elected leaders debate their own answers to the question of what makes an American, recalling, as they do, their own narratives of birthrights and bootstraps. Here at the magazine, we tend to answer that question of American identity as broadly as possible—why not be as inclusive as we can?—but it occurs to me that our first author in this series offers a particularly pleasing response.

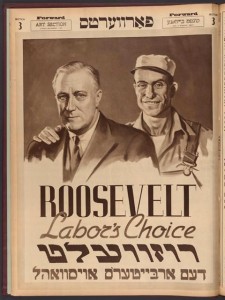

Abraham Cahan emigrated to the United States from his native Lithuania, where his revolutionary inclinations had gotten him into trouble, in 1882, at the age of 21. Though his ship docked in Philadelphia, he immediately made his way to New York City, and remained a New Yorker for the rest of his life. Cahan became the leading voice for the great wave of Russian-Jewish immigrants that swept over the city in the second half of the 19th Century, settling mostly in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As the longtime editor of the Yiddish-language Socialist daily, The Forward, Cahan presided over the curiously contradictory process by which immigrants at once integrated and settled into their new country while at the same time deepening their own particular cultural identities. (The fact that the paper continues to this day to publish an edition and website in Yiddish testifies to the remarkable resilience of the latter instinct.) In a wildly popular and long-running advice column called the Bintel Brief (“Bundle of Letters”), he earnestly answered the questions of readers faced with the daily dilemmas of assimilation.

Cahan’s fiction, too, is tangled by the twisting pull and tug of the immigrant’s loyalties in the brave new world. His work argues for an America defined not only by the ease with which it absorbs foreignness, but also by the eagerness with which, in turn, immigrants adapt the postures and poses of their new home to their own habits and rhythms. His protagonists are recent arrivals, alive with the hopes and sins of the young American, at once brightly optimistic and homesick in ways they don’t even recognize. Cahan’s initially simple-seeming realist family tales gradually slant in the light of their author’s gentle cynicism towards a more emotionally sophisticated narrative; he is amused by his characters—the dominant note in his fiction is a humorous one—but he never scorns them, and, reading on, one senses with appreciation the ways in which he leaves them room to surprise even himself sometimes. For the reader of Cahan’s fiction, this makes for particularly amiable encounters with characters that have both the bright charm of the caricature—the exaggerated gesture, the funny diction—and the softer depths of an intricate and resilient humanity. (The experience is like reading for the first time a letter from a neighbor you’ve long been chatty with —an immigrant who speaks with a heavy accent—and realizing suddenly that his English is flawlessly idiomatic.)

Poor Asriel Stroon, the tragi-comic hero of “The Imported Bridegroom” (our story today, long enough, really, to rate as a novella), could do with a little well-intentioned advice. The rich old man has done well enough in his adopted homeland to have almost forgotten the old country, but his advancing age pinches him into vague nostalgia, and a religious devotion he hardly knows how to perform. His daughter Flora, 20, American born, doesn’t know what to make of her fond and foolish father, and responds to his maudlin observances with good-natured skepticism. But she loves him, and there is real warmth in their exchanges, conducted on his part in Yiddish and on her part in an English loose with the “ain’t’s” and “don’t it’s” of the American vernacular.

It is on Flora’s fair face that the story opens, in a traditional little vignette, the girl’s head bent over a book while she dreams of her future husband, an American gentleman, she hopes, with shaved cheeks and fluent English. But Cahan has no intention of following through on this conventional beginning. The book Flora is reading is no sacred text but a “lump of Gentile nastiness” (as the newly-pious Asriel puts it): Little Dorrit, to be exact, a novel that presents a critique of the Old World’s rigid social class structures—structures her father has found to be far more pliant in the new one—but that also warns of the pitfalls of social mobility.

When Asriel returns, after an absence of many decades, to visit the Russian village that was once his home, he finds himself out of tune with the world he left behind, and despite his best intentions and many sentimental protestations, he relates to his former compatriots mostly as a businessman, by buying their respect and gratitude. His greatest acquisition of all, however, is Shaya, the bridegroom of our title, a gifted young Talmudic scholar who is half a mischievous boy, as yet, purchased for “thirty thousand rubles, and life-long board, and lodging, and bath money, and stocking darning, and cigarettes, and matches, and mustard, and soap–and what else?” In fact what Asriel is purchasing is the chance to bring a little of the piety of his childhood back to New York with him, and to save, he thinks, his beloved American daughter from her secular American future.

But like that devoted, impudent girl, Cahan’s story is forever striving to escape the bonds of tradition, and it outgrows the conventional marriage plot just as she outgrows her father’s plans for her. True, despite her vehement objections, she can’t help being charmed by the bright young man her father brings home, especially once he begins to study secular subjects with far more zeal than he ever applied to the Talmud. But, as Henry James did famously a few years earlier in his Portrait of a Lady, Cahan forsakes the public wedding celebration in favor of a more private uncertainty. Flora’s father, crushed by the youth’s betrayal, is not the only figure whose plans don’t pan out. The story ends on a surprisingly modern note that will ring familiar to anyone who has watched the final moments of “The Graduate”—another American tale of generational friction and a rebellious young man who doesn’t quite know where he fits in—and seen Dustin Hoffman and Katherine Ross’ faces go blank to the ambiguous sounds of Simon and Garfunkel.

But like that devoted, impudent girl, Cahan’s story is forever striving to escape the bonds of tradition, and it outgrows the conventional marriage plot just as she outgrows her father’s plans for her. True, despite her vehement objections, she can’t help being charmed by the bright young man her father brings home, especially once he begins to study secular subjects with far more zeal than he ever applied to the Talmud. But, as Henry James did famously a few years earlier in his Portrait of a Lady, Cahan forsakes the public wedding celebration in favor of a more private uncertainty. Flora’s father, crushed by the youth’s betrayal, is not the only figure whose plans don’t pan out. The story ends on a surprisingly modern note that will ring familiar to anyone who has watched the final moments of “The Graduate”—another American tale of generational friction and a rebellious young man who doesn’t quite know where he fits in—and seen Dustin Hoffman and Katherine Ross’ faces go blank to the ambiguous sounds of Simon and Garfunkel.

In “The Imported Bridegroom,” however, the gulf between the two generations is not as wide as it may seem. Asriel may shake his head at his “gentile” daughter, but in truth Hebrew is “a conglomeration of incomprehensible sounds” to him, too strange to serve him well in his prayers, which are in any case more purposeful than pious. Yiddish, along with a serviceable if heavily accented English, is his naturalized tongue. This seems, somehow, appropriate. Yiddish is the language of a diasporic people, a linguistic fusion born of the centrifugal pressures of emigration. His is a fitting accent for New York City—a verbal melting pot, rich with invention. The voice that Cahan gives Asriel rings out through the pages of his story with a new-world vigor that amuses his daughter. When she worries about his safe return to Russia, he reassures her of the protective power of his American wealth.

“The kernel of a hollow nut!” he replied, extemporizing an equivalent of “fiddlesticks!” Flora was used to his metaphors, although they were at times rather vague, and set one wondering how they came into his head at all. “The kernel of a hollow nut! Show a treif [impure] gendarme a kosher [pure] coin, and he will be shivering with ague. Long live the American dollar!”

At times like these, it is precisely their thick accents that make Cahan’s characters sound so American.

(“The Imported Bridegroom” was originally published in The Imported Bridegroom and Other Stories, by Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, 1898)