We are pleased to announce the contest winner and finalists from our Camera-Flash Fiction Contest. This spring, we invited you to write quick fiction based on one of eight vintage photographs we handed out at the AWP conference. After many hard decisions, here, in order, are our winners:

ASF CAMERA-FLASH FICTION CONTEST FIRST-PLACE WINNER:

After Taking on the Milk Challenge the Earth Bear Learns Something About the Nature of Human Experience

by Caleb Curtiss

Life gives us moments, cracks in the façade of our increasingly meaningless routines that, if seized upon, may come to define us. The Earth Bear knows this, knows how change is inevitable, largely uncontrollable. Yes, thinks the Earth Bear, who, at this moment, wants to physically transport himself into the past, but since he himself cannot augment the laws of physics, the Earth Bear uses his mind to remember the last summer he spent with his father, doing cleanup at the shop. Ugly work, yes, but the Earth Bear finds himself going back there often, back to one night in particular: the night his father took him to the rodeo. This is what cattle looks like before it becomes a carcass, his father, who’d just finished using what looked like a machete to peel primal cuts of beef from the bone and tendon that held them, said. It was the Earth Bear’s duty to sort what was left of the animal into three metal cans labeled Edible, Inedible, and Bones. These buckets and their contents were what he thought about as he sat watching cowboy after cowboy being thrown to the ground like plaid handkerchiefs. It was what he thought about a moment ago as he sat staring through an almost empty milk gallon, surrounded by his brothers who’d started to accumulate around him as word of his progress spread throughout the house. Soon, he’ll lean over a trashcan to produce a crystalline vein of bile-laced milk, reaching from his stomach to the bottom of the can, but now, he’s sitting, hands folded over his impressive belly, absorbing his brothers’ exaltations, watching another plaid shirt go flying, still thinking about those buckets, amazed at how the body can be dissembled, categorized, and repurposed, as if it, of all things, mattered.

Life gives us moments, cracks in the façade of our increasingly meaningless routines that, if seized upon, may come to define us. The Earth Bear knows this, knows how change is inevitable, largely uncontrollable. Yes, thinks the Earth Bear, who, at this moment, wants to physically transport himself into the past, but since he himself cannot augment the laws of physics, the Earth Bear uses his mind to remember the last summer he spent with his father, doing cleanup at the shop. Ugly work, yes, but the Earth Bear finds himself going back there often, back to one night in particular: the night his father took him to the rodeo. This is what cattle looks like before it becomes a carcass, his father, who’d just finished using what looked like a machete to peel primal cuts of beef from the bone and tendon that held them, said. It was the Earth Bear’s duty to sort what was left of the animal into three metal cans labeled Edible, Inedible, and Bones. These buckets and their contents were what he thought about as he sat watching cowboy after cowboy being thrown to the ground like plaid handkerchiefs. It was what he thought about a moment ago as he sat staring through an almost empty milk gallon, surrounded by his brothers who’d started to accumulate around him as word of his progress spread throughout the house. Soon, he’ll lean over a trashcan to produce a crystalline vein of bile-laced milk, reaching from his stomach to the bottom of the can, but now, he’s sitting, hands folded over his impressive belly, absorbing his brothers’ exaltations, watching another plaid shirt go flying, still thinking about those buckets, amazed at how the body can be dissembled, categorized, and repurposed, as if it, of all things, mattered.

FINALISTS:

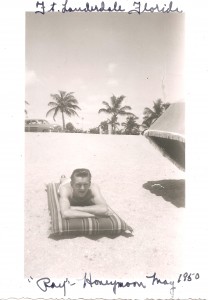

Ft. Lauderdale, 1950

by Lauren Becker

We were married on May 5, 1950. He had many superstitions, most involving numbers. I was superstitious, too, or maybe I became so after we met. I don’t recall much of my life before. He never forgot our anniversary.

He did not like being photographed and looks angry in the few I have. Even in our wedding photos, he appears to be scowling. We smiled a lot that day.

We lived in Pittsburgh then. My aunt and uncle were rich. My mother called my uncle a slumlord.

Their family spent most winters in Florida. For two weeks, when school let out for Christmas, when my cousins were young. For weeks or months when their children left for college.

I never thought much about the source of my uncle’s wealth. His wedding gift was our honeymoon in Ft. Lauderdale. I do not know why I labeled the photograph “Ray,” as though it were not his true name. He was born Ray Alan Berman.

Not even Raymond. I do not know why I labeled the photograph at all. I was young and took it for myself.

It’s not as though I would forget who he was or where we were or why were there or even that moment. My daughter jokes that I married him because my maiden name was Herman.

She teases that I was lazy and did not want to change my entire last name. I have few pictures of her smiling.

The photograph was taken on May 9. I was sunburnt and sat under the umbrella.

He turned brown and admired the contrast of my pink and white skin against his when we returned to our hotel, salty, and lay naked while the air conditioner whirred, a sound that still makes me shiver.

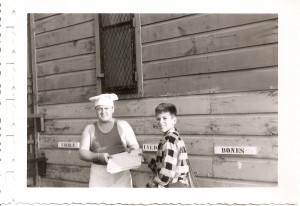

bones and cartilage

by Joanna Kenyon

Lord give me a Dmitri any day, or a Henry—thick lifting beater with billowing cook’s lid and an apron, tied just below the daily paper, carried slightly away from his body as if news burned; generous of chin, wide eyes and sweat poised on his skin in taut drops. Innards a croissant, oven hot: everything on the edge of melting, never quite but always just. Not like those cilantro lavenders or pepperoncini dills, rather more like that nuclear drift on a crisp Thursday, spring perhaps, stuffs you up but still sends you backwards, searching. Breath like a bourbon shot, whickering lines across limbs—although he too was initially unsure.

Which? he asked.

Edible, I told him.

Those belonging elsewhere: the vast swilling hoards, the savagely bitter, types too excessive for the dusky hours—as if brown sugar’d been mixed with corn syrup and fruit punch. Those like tenth day white rice, or American spaghetti, or a spice cabinet with only salt plus pepper, sometimes no pepper. Luscious skinny boys all tuck and no nip, slugs without the tails—you know, mac hold the cheese. I’ve had you too many times, boys. Sight unseen, I know which pile to toss you in, boys. I just lift the lid a little.

Some days I wonder where the bones belong, really. Snap cracking, gristle sucking, marrow to the last licking lip. Possibly inedible, those thin bedraggled, lining up behind their windows. The hickory or alder flavored, fingers touched by yellow and teeth bones garnished green. Boys who collapse into tarsaled and metatarsaled collections, ash without the fire beforehand. Perhaps you can be salvaged, fellows, pulled out of the pile, fellows; perhaps there’s something on them bones. I’ll open up, and we’ll see.

Untitled

by Kevin Fink

It happened during that same languid Indian summer, the one where we found the dead, deformed frogs in the dried-out Crooked Creek, the frogs with five legs and three eyes, and the ones that didn’t have any eyes at all.

It happened during that same languid Indian summer, the one where we found the dead, deformed frogs in the dried-out Crooked Creek, the frogs with five legs and three eyes, and the ones that didn’t have any eyes at all.

We rode our bikes along the dirt roads, kicking up a tan dust that took hours to settle back down to the ground, and at night we kept our windows open, while we laid on top of our sheets hoping for any semblance of a breeze.

They found the gun next to the paperboy in the woods, his hand gently resting on the sawed-off edges of the barrel, as if he was reassuringly patting it, commending it for a job well done. A thin layer of tan dust coated his shirt and body, made his hair sparkle in the evening sunshine.

At Marie’s Dine-In, people talked about nothing else for months. He was just a boy, just a nice boy. It was an accident. A God-awful accident. They ate their biscuits and gravy and eggs over easy and went throughout their day, waiting until their shoes and socks were off, until they were on their backs in the dark of their bedrooms, to let the doubt creep in, to let their horrible, tragic thoughts turn to the idea of something other than an accident, before slowly settling down into the back of their minds, like dust.

There Was A Certain Thrill

by Amy Butcher

Becky’s favorite thing she ever did was let Jackson watch her skinny-dip in the earliest hours of morning in the apartment complex’s pool. She put her laptop beside the water, tilted the monitor down so the camera could see her full-on—naked breasts and neck and thighs—and then began to peel off her clothing. They were employing Skype to let it happen, and every now and then, a virtual door would slam in the background—another user signing off—and there was a certain thrill in this: no one else knew that she was naked.

“Not bad,” Jackson said from his place a place a thousand miles away. He leaned in and exhaled as she tugged her panties off. They were pink, and in the feedback monitor at the bottom of her screen, they looked almost translucent, like there was no fabric on her at all. Above her, in the apartment complex, hundreds of people were still sleeping, and it gave Becky comfort to think of them: how they lay at peace in their twin-size beds while her body lit with morning light.

“Well?” she asked, smiling.

Jackson was eating a hot dog in a potato bun, and because he hadn’t seen her in months, he smiled in response, blushed maybe, though it may have been the light.

She liked to think of him missing her: that was always what it came down to, even when it did not, but it was hard to hold that thought when the water was so cold. Still, Becky slid down low, the surface moving slowly to cover her legs and then hips and breasts. Her nipples like shells, like soft pink islands in a soft blue sea. She’d always envisioned herself with a stronger man—sharper shoulder blades, jagged limbs—but with Jackson she was content just to look at him and smile. For years, she took bubble baths, and sometimes he’d come over to fold himself beside her in the tub. He’d sit Indian-style in the warm, shallow water, looking like a little kid. This was when she loved him most. Now she watched herself watch him on the feedback of her computer, all fuzzy and white and lagging from the static of all their distance.

“How’s this?” she asked.

“Great.”

An Issue of Blood

by Shawn Huelle

Mutti repeatedly jabbed her finger into my chest and said that chicks and bunnies, no matter how pastelly hued, completely miss the Easter point: The cheeping, pooping ball of blue fluff wouldn’t be resurrected three days after it died a week from now, and neither would the 59 cents I had wasted, a word which she pronounced like killed. I tried to protect the chick, but Mutti pinched my arm, grabbed my baby, and tossed it into the bathtub, where it ran around and slipped on the porcelain. Then she bound my head with my scarf, jammed my arms into my jacket and said, Now.

They were a crawling, green-gray mass at the bottom of a dirty aquarium, and I couldn’t tell one from another as Mutti’s hard hands steered me toward the tank. I was trying not to think about all the rubber-banded claws when she said, Bottom Feeders. Lobsters are bottom feeders; they eat other sea creatures’ shit and transform it into a heavenly, white, breadlike meat we can only eat after boiling the living lobster until it turns blood red. Then she moved her lips away from her teeth and again said, Now.

I learned at school that pelicans have big scoops on their faces, which they use to gobble up fish. Standing there, staring into its flat, black eye, Mutti told me that a pelican will use the sharp part of that scoop to stab herself in the heart and bring her hot, red blood out onto her white, snowy breast to feed her children.

Afterwards, locked in the bathroom, as I let my poor, hungry, blue, little baby chick peck at the bruise Mutti’s finger had made, I hoped my sinner’s flesh and blood wouldn’t kill it.

Caleb Curtiss‘ writing has recently appeared in, or is forthcoming from, numerous literary journals such as New England Review, Passages North, Hayden’s Ferry Review, PANK, TriQuarterly, and others. He lives in Champaign, IL where he organizes the Pygmalion Literary Festival and edits poetry for Hobart: another literary journal.

Lauren Becker is editor of Corium Magazine. Her work has appeared in Tin House Flash Fridays, Los Angeles Review, Wigleaf, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. Her collection of short fiction, If I Would Leave Myself Behind, will be published by Curbside Splendor in Spring 2014.

Joanna Kenyon received her MFA in writing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She currently teaches composition and creative writing at Whatcom Community College, where she is also the writing editor for their journal, the Noisy Water Review.

Kevin Fink is a 2009 graduate of the MFA writing program at the School of the Art institute of Chicago. He has written for various websites (such as the now defunct TV Gasm entertainment site) and has had short fiction published on Fiction at Work‘s website, as well as their Biannual Report collection published by the Green Lantern Press in 2010. He currently lives and works in the Kansas City area.

Amy Butcher is a recent recipient of the Olive B. O’Connor Creative Writing Fellowship at Colgate University and is a recent graduate of the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program. Her essays and short stories have appeared recently or are forthcoming in Tin House, Salon, Kenyon Review, Indiana Review and the Rumpus, among other places.

Shawn Huelle‘s work has appeared on mississippireview.com and Wunderkammerpoetry.com, as well as in fold:the reader, Fact-Simile, and Horse Less Review. He currently lives and teaches in Tübingen, Germany.