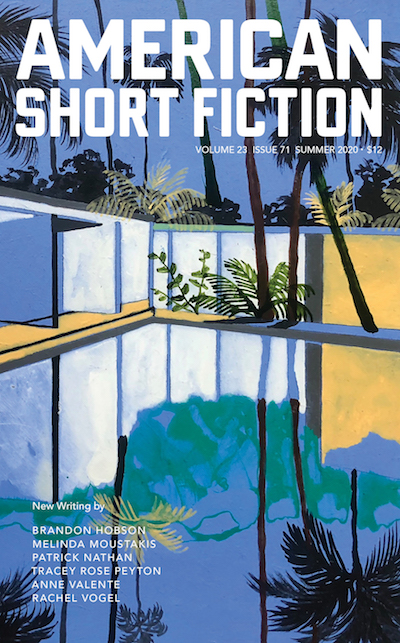

Featuring new stories by Brandon Hobson, Melinda Moustakis, Patrick Nathan, Tracey Rose Peyton, Anne Valente, and Rachel Vogel. Subscribe now to receive the Summer issue.

He was known most everywhere—a face, a caption, a grainy video clip—but it had been over twenty years now, and he was still trying to forge a new chapter unconnected to the first. Wishful thinking, he knew. It would always be connected. No one would ever bring up his name without mentioning the past, without talking about the public spectacle of a private beating that almost killed him, but didn’t. And when his heart slowed and breath filled his lungs, he was someone else.

It wasn’t amnesia. He knew he was the man on the tape. He could piece together the jumbled happenings of how things spiraled out of hand. How he misheard the first officer and moved away when he was ordered to stay put. Police didn’t understand things like reflexes, how the body rises up on its own to stave off danger. For years after, he practiced forgetting. Cough syrups that made sleep blacker than night. Pills with complicated names he got from therapists, which he crushed and chased with liquor until every memory was as distant as a picture show.

—

Three more ounces of Hendrick’s, some Dolin, a brinier splash than before, no olives. I asked for water. The hotel was only five minutes away, but a DUI wasn’t worth the risk. Not, we agreed, in such a godforsaken place. “They’d put us to work in the mines,” he suggested. “We’d never see the sun again.” I held my glass like a precious candle, petting its rim, and he laughed. “We would be absolutely alone, Katie. In utter darkness.”

By now the mountains outside had slid slowly out of view. Tomorrow we’d head toward them, on our way to Missoula. Every day we drove slower. It wasn’t about the beauty or the landscape. It wasn’t about America, whatever that was. But how do you tell someone, It’s okay to be afraid, when you can’t imagine his fear?—when, right now, he seemed as though he had no fears at all?

—

“I just thought of another,” I say. “At the Salty Dawg Saloon no one loves you more than yourself. No one hates you more, either.”

The man with the white beard leans over. “At the Salty Dawg Saloon,” he says with a slur, “loneliness is rope you don’t know you’ve tied until you’ve gone too far and too long.”

“That’s a good one,” I say.

“At the Salty Dawg Saloon,” says Talya, who by now has had more than her usual, “the one you thought was the one—” She rubs the condensation on her glass with her thumb.

“You going to finish that thought?” I say.

“The one I thought was the one,” she says, “was just one of the ones.”

—

Carolanne drives slowly on the dark rural roads, bumping over railroad tracks. Skunk stink drifts through the vents. Frank’s glows like a beacon, the only open establishment for miles. Carolanne pulls up to the curb but keeps the engine running. A deep patio fronts the restaurant, set off by an iron railing. Two thickly muscled men guard the entry.

Young people jam the patio, most holding bottles of beer. Despite the cold, girls wear slip dresses or midriff tops paired with tiny shorts. The boys wear jeans and T-shirts, though a few have on khakis and button-downs. One boy is vomiting into a trash can. They must all have fake IDs. How else could they get in? With a jolt, Carolanne understands that Juliette must have a fake ID, too.

—

Berta read online about missing Native women. Tania from Washington went missing after her shift at the hospital, just three weeks shy of her thirtieth birthday. Her body was never discovered. Sara from Albuquerque disappeared the night of her high school graduation. She was missing eighteen months, never found. Twenty-six-year-old Krista’s body was pulled from the murky water of a lake in Montana. Ashley had been missing for three years in northern Arizona, never found. Gina, a dental hygienist with a newborn daughter, had been missing in Oklahoma for three years, never found. There were the Marlenes, the Wanesias, the Ericas, the Jennifers, the Janets, the Lucilles—all still missing.

Berta read so many stories she forgot the names, except one. Near Falls Creek, Oklahoma, a young girl drew a circle in the red dirt. In the middle of the circle she wrote her older sister’s name: Jodi. Berta read the story at the table one morning, and it sparked a memory of Kara as a young girl, sitting in the backyard at her grandmother’s house, drawing circles and faces in the dirt with a stick. As Berta read about Jodi, the rose bush outside began to beat against the kitchen window from the wind, and Berta felt overcome with sadness and fatigue. Jodi was eleven when she disappeared. Her body was never found. After three years of searching, Jodi’s mother struggled with giving up.

“All the police do is tell us to keep hope,” Jodi’s mother said. “How are we supposed to live our lives? How are we supposed to keep hope after so long?”

—

These fucking ghost girls are ruining my life, Randy declared two weeks later at Shockey’s Sports Bar and Grill, where we sometimes gathered to watch Cardinals games. The Cards had just scored a grand slam when Randy thumped his pint down on the table.

It’s something new every goddamn night, he said. Bathroom lights left on. Juice glasses thrown off the kitchen counter. Faces appearing in our windows, beside our bed. It’s stressing Lisa out. It’s no good for her to be this nervous when she’s trying to get pregnant.

David nodded, his hands curled around his beer. We knew he and his wife Megan had undergone IVF treatments while also starting their own accounting firm, that the treatments were the reason they had twin sons, that they’d started trying just two months after launching their business and one month after Megan’s father passed away of an unexpected heart attack. We knew, even if we never said it, that the women in our lives quietly carried so many burdens beneath the shallows of polite conversation, things they never spoke about, things that seemed easier to leave unsaid.

—