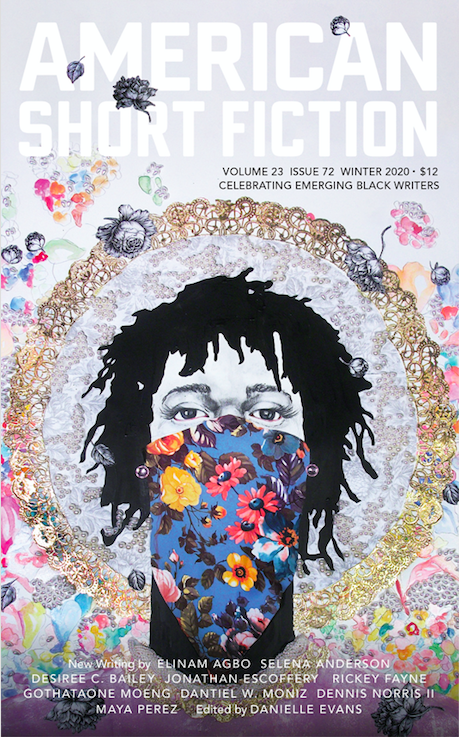

Celebrating Emerging Black Writers: Featuring new stories by Elinam Agbo, Selena Anderson, Desiree C. Bailey, Jonathan Escoffery, Rickey Fayne, Gothataone Moeng, Dantiel W. Moniz, Denne Michele Norris, and Maya Perez. Guest-edited by Danielle Evans. Read the editor’s note here.

The dead come for all kinds of reasons. They come with warnings, wants, and every manner of grudge. Though most I’ve seen come wanting. They come wanting everything you have and can’t give.

Some of the ones that come to Pa are soldiers from across the waters. They come trying to figure what happened and why. Why did they have to die and what was it all for? He tries to tell them that he doesn’t understand it any better than they do, but they don’t believe him. If he’s living and they’re dead, he’s got to know something, don’t he? He never actually gets to where he can hurt anybody, most times because there’s nobody to hurt, but it’s right worrisome for him to ride around with a loaded gun on his lap.

—

It wasn’t exactly second sight. Syreeta wasn’t sure what to call this ability to gaze at a stranger across the table and at the same time sneak into the hidden regions of the heart, opening all the safes, garbage chutes, and mailboxes. She found the secret meaning in other people’s quiet looks, and this knowledge made her rich in correctness, an expert at being right. Syreeta’s true gift was being 100 percent right 100 percent of the time. This was how she knew when a fire would start and why, if a suicide went unattempted, when a drug deal would go left. She could tell from the freshness of your fade how close you were to eviction. The way you walked into a room told her all she needed to know about your relationship with your father.

—

The air is electric in the still before a hurricane, and now, a cool breeze raises Delano’s arm hair. The curtain of humidity that hangs over South Florida is lifting. A storm is coming, and Delano finds an odd sense of euphoria in accepting the fact. He’s never seen men so content as when they have to abandon the menial tasks put on them by their nine-to-fives to come home and board up their houses; to leave what does not matter to protect what does. The farce of daily life is put on pause. The weather transcends small talk: Could this be the next Andrew? Andrew’s name is always invoked—South Florida’s Christ-event, their marker for before and after.

—

Everybody and dey mudda know dat when yuh hold di conch shell mout to yuh ear, yuh go hear muh voice ringin tru yuh head. “The sea,” dem people does say in a dreamy little voice. “The song of the sea.” And yes, dey know di song but what dey doh know is di notes. And dey doh know what makes up di notes, like where di notes come from. Yuh know that fish does sing little songs in di morning, or in di evenin when dey swimming tru di coral? Well some ah di notes come from dat. And when dem children kickin up foam and laughin when dey fly dey kite on di beach? Right, well, some ah it come from dat. But yuh wouldn’t believe that some ah it come from wickedness and evil too.

—

My roommates and I, we ran out of food and out of money to buy more. We watched pirated movies on our laptops: love stories and romantic comedies. We wanted love, and to be literate in love. We wished to fall in love with the men we watched on the movies. We wanted heartbreak, but only enough that our hearts required no worse cure than languishing in bed with a tub of ice cream. Some of the men we knew told us, Ke go rata lorato la o ka swa nka go ja, and we were afraid that they would love us to our deaths and that, even in our deaths, they would consume us. Some of the men we knew declared their love to us in English, the language a deception, a second skin they donned and shed as they wished. We fell in love with these guys, swept up in the slipperiness of their words, their declarations. We were in love. We thought we were in love. We felt sure it was love, this time. We made love after making them wait for months. We had sex with one, two, three guys in a year, parceling out pussy to convince them we were marriageable. We abstained from sex for six months at a time, for twice that, convinced it made us better, virtuous women. We fucked three, five, seven guys in one month, our bodies rapacious and unashamed. We fucked them on the same alcohol-fueled, laughter-drenched nights we had met them at a bar. We abstained, fearing disease. We wanted love, oh, we wanted love, but we knew, we had been warned, that for girls like us, love was dangerous, a bright-burning flame, it would lick us alive.

—

Comfort is fleeting. A warm sun in the last days of fall. After the honeymoon phase of “Welcome to America,” with the mall tours and Costco samples and Chinese-buffet dinners, my new father began to blame us for his poverty. Our presence had brought little luck and no relief, and he stopped asking about our day, choosing instead to wear his proud and brooding “I am the Breadwinner” shirt, returning home late at night, red-eyed and irritable, the promise of control clinging to him like an addiction. By then, there was nowhere to run. We were dependents—my mother and I—we who did not recall how sour depending on others could be.

—

This place is grim, the Reverend thought, and it trains you in its ways. And at eighteen, Davis’s existence was made entirely of moments—glimpses of joy and heartache and everything else. A young life was episodic; Davis’s understanding of the world relied heavily upon fumes—notions, impressions, ideas, and questions. What few experiences he’d lived were fleeting. The Reverend knew he deserved his son’s anger and, more than that, his disappointment. But it didn’t change the slow realization, as the Reverend stood watching, waiting, and listening, that Davis, though desperately wanting to be free of his father, simply wasn’t ready. He was bruised; by whose hand was of no importance. He had no business in a grim city like this.

—

He was big on eye contact, disconcertingly so. Violet didn’t remember this about him. No checking his phone, no glancing over her shoulder. Maybe he was on medication. He stood as if simple movements took great effort—arms hanging long by his sides, rooted legs. He looked tired.

“Are you doing okay?” she asked Doug.

“What do you mean?”

“I don’t know. I mean, what are you doing, what have you been up to?”

“I’m a botanist,” he said.

“Plants. That’s cool,” she said. He didn’t offer any more information.

Violet fought the urge to ask him another question and held up her takeout bag, “Well, it was nice running into you, but I need to eat before I go to work.”

“I just got back from Mars,” he said.

—

I understood stress and, unlike him, could articulate mine. I was twenty-three and already starting to get nervous about so many things: aging; inhumane healthcare and the endlessness of student loans; the growing anxiety that I might not be good for much else than serving other people. I worried that we were crazy to get married so young but was too conscious of social stigma to admit it. I felt alone. Lately, unless I drowned it out with drink and dance and work, other distractions, all day a voice way in the back of my brain, real calm, sang: Dumb girl, you’ll die this way.

—