“So what do you say?” Marlon asked, standing up and grinning. Something about his unabashed drunkenness, his gleeful childlike pronouncements, complemented his broad shoulders. “Party with us?”

Was it blood that zoomed to the FAMOUS SINGER’s cheeks or just maternal pity? Being handsome and pathetic was Marlon’s selling point. Mothers adored that poor fellow brimming with wasted possibility. “Fine, but I need to drink my lemon water,” the FAMOUS SINGER said, and the crowd of cousins cheered. Everyone snatched a bottle of leftover Hennessy, a takeout box of lobster scraps and fried rice drenched in lobster juice, and then rallied to RICH MING’s rental home.

—

He rang the bell by the front door and was buzzed in without having to explain himself. The hallways were air-conditioned and he relaxed. Sadie had been enchanted by The Schoolhouse when she visited her mother, but Jack knew that no place once devoted to the education of children is enchanted without also being haunted. He could smell, quite suddenly, gym class. Not kindergarten gym class—cinnamon toast, artificial fruit, the squeals of five-year-olds allowed to run at top speed—but sixth grade. Half the girls budding, three or four in full bloody bloom. Boys, too, with wobbly chubby tummies and weak arms. The smell of burning flesh: thighs on climbing ropes, knees on the floor, what Jack would have called Indian burns. Maybe they still called them that. Lunch: square pizza, pickley tuna salad. Smoke from the teachers’ lounge. Turning a school into a residence, thought Jack, was as bad as building your home on top of a cemetery.

—

Why the name Red Sensei? He had bleached hair, pale skin, white robe, and black belt. He was short and densely packed, kind of waterlogged looking. He often wore a Rush T-shirt, which peeked out behind his robe and made me anxious, like when you can tell a doctor’s wearing normal clothes beneath his doctor clothes. It turned a uniform into a costume, temporary.

He was keeping a notebook on each of his disciples. That’s what he said. If we finished three years of training, he’d give us the notebook as a reward. It’d be like living in a studio apartment all our lives and then someone handing us a key to rooms we never knew existed. Except the apartment was us.

I imagined him in his office after we left, jotting down his observations. Noticing us, assessing our potential, charting courses, around our limitations and all the things that scared us and shouldn’t have, the things that didn’t and should have, away from the helpless futures that awaited us. Toward what, I had no idea.

—

These are the facts:

1. He was born on a boat in the Pacific Ocean.

2. He had a brother who used to be in the navy.

3. He met my mother at Ampex, the electronics factory in Taiwan where she worked on an assembly line building the world’s first mass-produced 16-track professional tape recorders. I was not sure what my father did at the factory other than read girls’ palms, which was in actuality merely an excuse to hold their hands.

4. He is remarried with at least two sons. The oldest son is approximately sixteen, and the other is ten or eleven.

5. He lives in Rowland Heights in the Inland Empire on a street called Walnut Grove. This information was gleaned only by looking him up on the internet.

A father reduced to a handful of anonymous facts, facts that could belong to anyone. One ocean, one brother, two sons, a factory, a street named after a coppice of deciduous trees.

—

Because what is any living human going to say in this moment? What is any living human going to feel other than complete and utter tenderness and love for this woman and her ferret? I love Paris Hilton and her filthy house and her filthy yard. I want to hug her, in fact, until her bones break and clean up every jewel-like piece of shit in her strange and confused living room. Love briefly floods me for every living thing upon the earth. The only thing I find I do not love however, is myself. A horrible party-crasher and social contaminant, here under false pretenses to witness this near perfect moment of naked vulnerability.

—

“I am not sure he is such a good husband,” Dorothy had once said to Elizabeth about Mark over the phone, just before her stroke. She had been quizzing Elizabeth about money, whether Mark was making any, teaching one class here, another there, still hopeful about his writing, and it was the only time Dorothy had ever insinuated that there was anything less than perfect about her son or their marriage.

“He’s fine,” Elizabeth said, leaving some room for doubt in her tone. Why? To be cruel or because she craved some version of Dorothy’s unconditional love, the kind of love that smoothed over uncertainty, that settled things? Or perhaps her mother-in-law knew something about Mark’s black eyes, which rarely revealed much of what he felt, or about his turning away from Elizabeth at night.

—

Carla’s only takeaway was that she needed to meet this Ricky. She’d never heard of a guy like him. Ed talked stocks. Her missing father had talked shit. The boys at school didn’t talk at all. Where was this Ricky with his emotions and simulated jewels? Did he know his way around a florist? A Hallmark? A vagina? A heart? Carla knew she should be thinking about college, a career. Shopping centers. But Richelle’s story confirmed what Carla had suspected about herself all along: that she just wanted to be held, to have her hair brushed back from her face. Real estate wasn’t going to look her in the eye and call out her name.

—

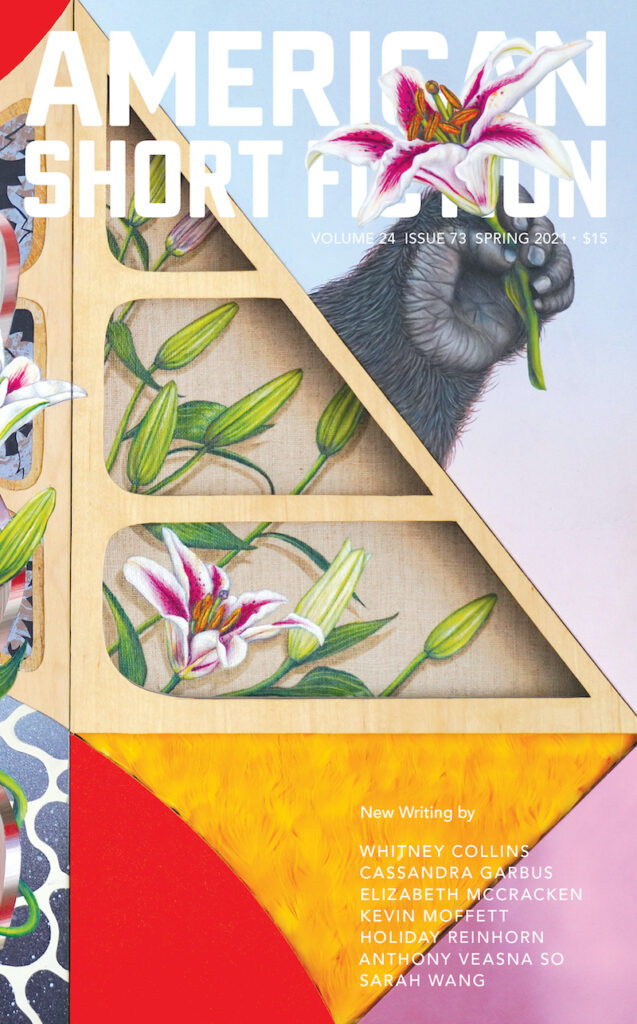

ASF Issue 73 Cover Art by Christian Ruiz Berman.

—