Featuring new stories by Sanjay Agnihotri, Mala Gaonkar, hurmat kazmi, Taisia Kitaiskaia, Morgan Thomas, and Kirstin Valdez Quade.

Laura’s breasts notwithstanding, the summer seemed to be shaping up perfectly. But then, toward the end of June, Mr. Swanson from next door ran away with an eighteen-year-old girl who worked at the Breezy Freeze. “Of course I knew about her,” Laura overheard Mrs. Swanson telling her mother in the aluminum carport. “But I didn’t know he’d leave with her. And to Los Angeles!” Mrs. Swanson sobbed into her hands as if she could have borne it if they’d gone to Denver or Wichita.

Laura had a great deal of disdain for this sort of female misfortune. No matter how you sliced it, it was undignified: to be so distraught to have been left, and to have been left in the first place.

—

When I admitted to Griswolde that I could barely point out the Netherlands on a map, let alone imagine the connection between the Netherlands and Iceland, Griswolde was very slowly peeling a grapefruit in our dining room. Our dining table is a beautiful, hundred-year-old slab of marble, a strange pairing with our scavenged chairs. Griswolde hulking at one end and I on the other, like royalty from the old days.

“Olyona,” Griswolde said, “this is precisely why I came to America. To find out these things, such as how can a country so wealthy be unaware of geography and history? And how can a country so wealthy be at the same time without food or electricity?”

Griswolde’s hands were strong, and the grapefruit peel came off in a few long strips. The peel shone in the dark room. Griswolde had grown the grapefruit tree in our yard himself.

“I wanted to see for myself,” said Griswolde, shaking his head, “what it was like to live here, in a nation that had ruined itself.”

—

The post of the German monk garnered seven thousand likes. Let grief’s horse run, then leap off, he had said. But where did my son end, and I, his mother, begin? When he fell ill, I had, like some bear preparing for a long icy hibernation, fattened myself on self-righteousness: it is all for him. Every time I think about the future, I tear up the pages of my past. Were the women herding cattle in the valley as decorously resigned as I had wanted them to be? Was the boy dragging his cart of treats up the hill truly smiling that sweetly? We can never trust memory. I was once told by a temple mahout that if you cut open an elephant, you would find his heart weighs thirty pounds. If you cut me open, what weight could you measure of all I have learned and said and written and thought of you, my son?

—

She mistook me for a vampire. It’s an easy mistake to make.

I was traveling alone. I was pale. I wore black jeans, black T-shirt, black jacket. I’d come from a three-month stint at the Naked House, where parents send kids who refuse seconds, refuse to spread peanut butter on their celery sticks. I’d been expelled from the House, not discharged, so I was still bony and furry, still inclined to eat dinners of only spinach, to feed privately in bathroom stalls or crouched by the waste bins.

I was stranded with everyone else in Jubilee, Louisiana, my train delayed by flooding. We’d been stuck for five hours in the SunTran Station, where the water fountains were dry, the soda machine out-of-order. We were all thirsty. It’s hard to tell from looking who’s pining for Gatorade, who for liquor, who for blood.

—

When it was just us, the three of us, at Khurram’s house or Aatir’s or mine, we did not want anything more. We sucked on mints or chewed Juicy Fruit. Our lips were always moisturized with Vaseline. Ours hands smelled of pomegranate and cucumber lotions. We slipped into delirious fits of laughter, and our guard came crashing down. We did nothing special. We mixed Pepsi and 7UP and pretended we drank champagne. We gossiped about our teachers and discussed faculty politics, things Khurram overheard from his mother: Sir Ijaz and Ms. Naheed scandalously shared a ride to school; Ms. Faiqa did not actually take a Hajj leave, she was getting married. We laughed and laughed and laughed till our stomachs hurt and talked and talked and talked till our jaws tightened, and it was time—it was always time—to go back to the mad, bad world.

—

Raj lifted the box at the head and Showkat took the feet.

“It’s much lighter than I thought it would be,” Showkat said, brightening.

As they made their way to the steps, the body shifted inside the flimsy box like a loose package banging around. They took two steps up the staircase. The body was still sliding. Raj could see the blood draining from Showkat’s face, the fake chain weighing him down. He was afraid the kid might pass out.

“Almost there,” he said. “Almost there.”

Raj tried to hold it steady, but the box slipped a bit from Showkat’s sweaty, trembling hands. “I don’t know,” he said, his voice quavering, “I feel almost like it’s my own mother inside.”

At the top they adjusted their grip on the coffin. They walked across the thick maroon carpeting, the sound of sobbing coming from faraway rooms. The body still slid around in the box. Raj wanted to tell Showkat not to think about it, but his legs too were giving out, his head throbbing, his breathing labored. At last they made their way outside into the thick, citronella-scented air and down the steps, around the back of the funeral home, away from the flood lamps. Staying in darkness and out of sight of Polito and sons, they carried the stolen casket to the Lexus.

—

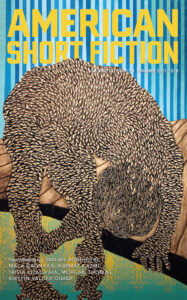

ASF Issue 74 Cover Art by Didier William.

Kirstin Valdez Quade, “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool”

Kirstin Valdez Quade, “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool”