Featuring new stories by Lydia Conklin, Darby Jardeleza, Matthew Neill Null, Roger Reeves, Eric Schlich, Caroline Schmidt, Jackie Thomas-Kennedy, and Emma Törzs.

A hangover was already running her down, her lungs full of fiberglass. En route to the subway, a rat skittered from under a bulkhead door down the sticky, empty street and into the neon light of a taco sign. The rat carried a mouse in its teeth. The mouse’s eyes were points of light straining through his fur. He was alive.

—

My situation is quiet apartment with walnut floors and Carrara marble in the bathroom. My situation is reserve wine and trips to Europe, dinner parties, custom suits, fountain pens, signed books, and niche cologne. Lasca says my watch looks like a nice car. It does contain a forty-piece tourbillon and it does not make a sound. A tourbillon is no scientific achievement, but I wear the watch as art, and function is ancillary to aesthetic in this and most respects. I work at a bookstore. I don’t make a substantial living. But I live only for myself, so I am a rich man.

—

Robert’s real name was Cheung Xi, which Troxell knew only from the customs forms and wasn’t sure how to pronounce; Troxell currently had $29,000 worth of dry-weight ginseng that Robert would not be purchasing, along with lesser piles of yellowroot, mayapple, and cohosh. The coal miners of Nicholas County said of Troxell, “He getting rich because some men can’t get their dicks hard––that’s why there ain’t no local demand!” Yes, they said, he had to travel internationally to find soft-enough dicks. You never met a coal miner had that problem! They talked like this in the bathhouse, soaping themselves. But let them make fun, Troxell didn’t care, they won’t be laughing when they’re coughing up black lung in the hospice and he’s living it up into ripe old age.

—

Elle’s mind roamed like this, moving off into quick snatches of story, into what she sometimes called “foolishness.” Sometimes, she allowed herself forays into “foolishness” as she swept, dusted, mopped, hurried about the Otis’s house. She allowed herself talking snakes in swamps, bears coming out of the woods and carrying off children into caves, rams that conversed with God, argued with God. And, for arguing, God imprisoned the rams in bushes to be sacrificed on a stone table later. Even romance. Elle allowed herself a little wandering into romance, which had been so far from her since her husband took sick. A tick of sweat, the tips of a man’s fingers moving along her ribs until her breast sat his palm and his mouth against her neck. “The blood of Jesus, the blood of Jesus,” she’d whisper to herself, hoping to stave off lust.

—

Henny’s teasing had been one of their problems. They did not share a sense of humor. They used to do the Sunday crossword, and once, when Henny was bored, she filled every square so that the word fuck repeated itself, then folded the page and tossed it back to Patrick, who stared at it, blinking.

“How are you not laughing?” she’d said. “Not even a little?”

She was immature. So what. She had a high voice, wore a size six shoe, looked good in overalls. Sometimes she wore her hair in two braids. She wouldn’t try new foods. Immature, yes. Also beautiful, or so he used to tell her. Also good at her job, Director of Alumni Relations for a school she hadn’t even attended. She was good at simply deciding to belong somewhere and patiently waiting for everyone else to catch up.

—

A few weeks after we met—in the MFA program where she taught and I studied—the novelist told me she’d first been drawn to me because I reminded her of herself at my age: twenty-three. She was then sixty-eight. When she told me this—“I liked you because you reminded me of me”—I nearly cried, because I knew that at twenty-three she had hated herself. I knew this because my brain was in fact an exact copy of her own twenty-three-year-old consciousness, and I cried because it moved me (in every direction) to think you could love yourself better from the outside.

—

I’d heard this story of the earthquake before, embellished a little more each time. Still, as I watched my wife lean across her stomach to reach her plate at the kitchen table, I envisioned for the first time the shuddering of the earth, the movement of stone and soil. We’d gone that morning to my mother’s house for breakfast, had made the slow trek to the suburbs. The boxy yards and mailboxes, the hummingbird feeders. The spindly bodies of the deer appearing in the road. The house itself I cannot recall now: it was so familiar to me that I’d never stopped to study it. This was where I’d grown up, where my father had died, where—in five years—my mother, too, would die. Where had we kept the magazines? What color were my bedroom walls? What painting hung above the living room couch? Sometimes, a flash: my mother in the pale morning light, a cracked blue teacup in the sink, a comb, tangled with hair.

—

Once it reached Rasputin-length, she went pirate chic, knotting it into beaded ponytails like Captain Jack Sparrow. She went through a phase of beard art (also a thing) in which she’d mold it into interesting shapes: spirals, zigzags, tentacles. Holidays were particularly torturous. Our nieces and nephews loved seeing what she’d come up with. At Halloween, she hung bats. At Thanksgiving, she shaped it into a cornucopia and filled it with miniature gourds. For Christmas, she strung battery-operated lights and tinsel, clipped a star at the bottom for the final touch: an upside-down tree. I’m still tracking glitter from New Year’s. But Easter—Easter took the cake. She braided it with flowers. Simple, I thought, elegant—until I heard chirping.

—

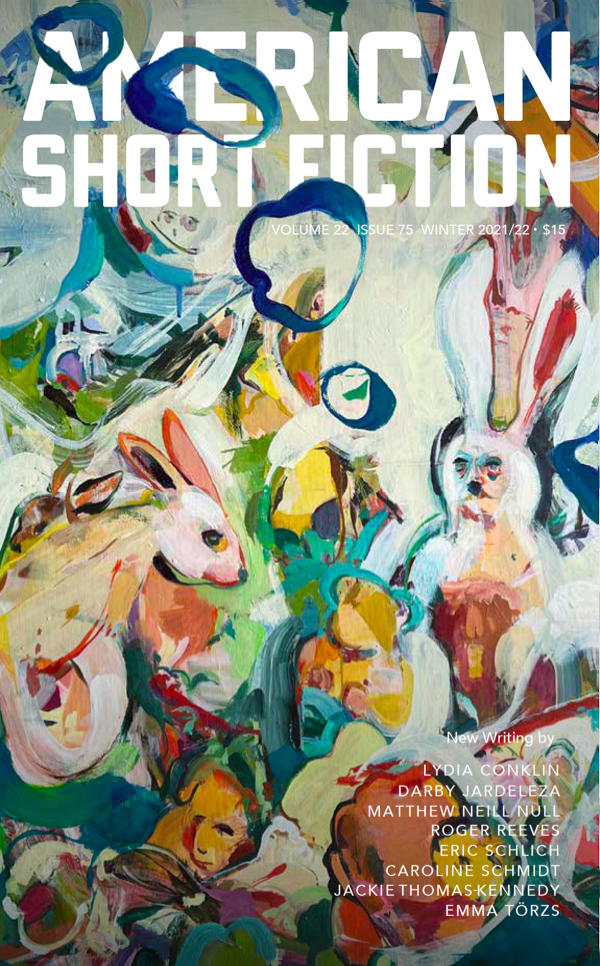

ASF Issue 75 Cover Art by Eric Uhlir.

—

Lydia Conklin, “Belong to the Night”

Lydia Conklin, “Belong to the Night”