Featuring new stories by Jeffery Renard Allen, Jamel Brinkley, Mala Gaonkar, Anita Lo, Yasmin Adele Majeed, Emily Mitchell, and Max Ross.

You know, only a fool does something for free, the Champ said. I’ve been thinking about how to repay you. A word stalled on his tongue. It sounded like farty. She had seen it in him before, the blur while thinking. Wait, he said.

With evident excitement, he retrieved his top hat from the coat rack, pulled his retractable magician’s rod from the side pocket of his cashmere great coat, and extended it like a blind man’s cane. Then, employing grand stylized gestures that were as antiquated as they were timeless, he tapped the cane against the topper one two three, causing a cloud of smoke to explode canon-like from inside the hat, which shrouded out into white filaments that dissipated into a wondrous sight: a colorful parrot that fluttered up and perched on the Champ’s forearm. The Champ smiled at her and she smiled.

Then the parrot spoke: Let me throw you a birthday party. Sweet sixteen.

You want to throw me a party?

Yes. Me and the Champ. Clowns, camels, corndogs, cotton candy, canapés, cannoli, Crush, and cable cars.

Was it a real parrot or some sort of ventriloquist dummy? She could see the Champ’s lips move with the bird’s mouth. Her question was answered when the bird took to the air and started flying about the room.

—

Ghosts have been in my family for generations, but the ones on my father’s side tended be of the flimsier sort, available more to the ears than to the eyes of the living. His grandmother left behind her Sunday-afternoon humming, for example, and his disabled uncle persisted in the heavy step and drag, step and drag, along the length of his porch. My mother, on the other hand, had the telltale visibility and near-corporeality of many of the ghosts on her half of the family. This quality made it difficult for living witnesses to keep the necessary boundary, to distinguish between traces of things and the things themselves. You could treat the ghosts of my father’s people like an overheard phrase of a familiar tune, taking notice of it and perhaps, for better or for worse, remembering, but only for a moment. With a ghost like my mother, however, you had to be careful. Before you knew it, that quivering body would firm into a pillar, around which your entire life, here and hereafter, would everlastingly revolve.

—

Each dawn, the string of bells we found in Jaipur on our honeymoon and hooked on the bedroom door jangled as your father left for his university office. In those early hours, the sky a purse of gray silk, I stayed in the remnants of his embrace, the sparse cars threading through the empty streets, the thin bell clappers faintly sounding like the slippery seeds in the old, dry gourds we played with as children. I told myself, I am happy.

—

“How is your mother?” she continues. She drapes herself with a thin gray sheet, which enhances the impression that her skin is slowly slipping from her bones.

I say, “Good,” because what do I owe this wilting woman whose laundry hangs captive from a patchy net?

Then she asks, “How is your father?” The scents of fresh sweet buns and earthy tea swirl in the dim light, and I squint to make out the steamer basket and teapot balanced precariously on a stack of cushions next to her.

“Good,” I repeat.

“You lie badly,” she says. “Let me ask this way.” And though I will spend many months with her over the years, my clearest memory is the measured way she leans back into her chair, her flared nostrils and closed eyes when she begins to speak.

—

The saint’s grave was located beneath a famous masjid, and my father weaved us through the crowd to a trellis, where a dark stairwell led down into the shrine. A subterranean room glowed with green, fluorescent light meant to reflect the colors of our national flag, but the effect was eerie in the dark. Years later, in the Bay Area, I would be reminded of the strange light of that tomb, how similar it was to the neon caves of clubs and raves. Strange that the grave could follow me there, across the ocean, in a new country.

—

In court, he is known for his short temper and severity. He is married, but he has no children. His wife Anna is the daughter of John Bradfield who was Sergeant-at-Law under Charles the First. He prizes his wife dearly and has often paid her the supreme compliment of saying that she would have made an excellent lawyer, if she were a man.

On the first night of the fire, Kelyng was at home in bed in his house near Temple Bar. He did not learn that anything was wrong until his servant Thomas woke him in the morning to tell him all the buildings by the river were in flames. Kelyng woke his wife, and together they went up to the garret and looked to the southeast. A wall of black smoke rose above the roofs in that direction. London Bridge was one long arc of flame. They could hear the sound of it, a low roaring like a vast hole being torn into the sky.

—

We’d come together when we were thirty, after years of being friends. It was a careful marriage, a quiet marriage, lamplit, reasonable, films and books, concerts and artist talks, separate laundry. We were both private by nature, Rachel a little more so. Taking her pregnancy test a few months before, she’d stayed in the bathroom with the door closed. Her instinct was to find out the results by herself. But I’d thought we should be together—we should be together, I’d thought, not quite felt—and I’d knocked and she’d let me in. And that was our marriage: the tendency toward privacy, the knocking, the being let in.

—

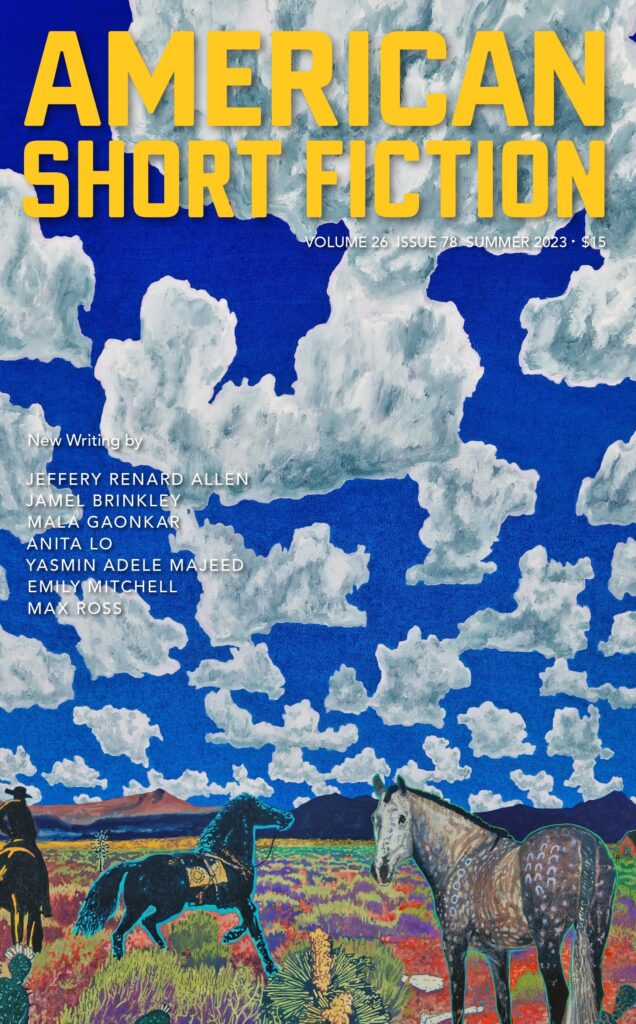

ASF Issue 78 Cover Art by Aaron Morse.

Jeffery Renard Allen, “Orbits”

Jeffery Renard Allen, “Orbits”