That’s the book she cracks as soon as she’s fought off her little brother for the back. Not a hatchback, that is a decade in the future, but the way back, where the station wagon’s nasty final seats never get pulled up into position, the one with the backwards view, her preferred. The roads to the north are pretty straight—what is there to bend them?—and except for a series of smooth dips that everybody shrieks through, flat as the pancakes she had for breakfast. Perfect for extreme terror on the water at two hundred-plus pages. She reads into the first slaughter, the woman with her legs hanging down, the giant shark tracking her invisibly, going for the gore, she reads for miles and miles and has only tucked her feet a little tighter under her when she starts to gag.

Hey, maple syrup, nothing special. She had to give her little brother the last bite of the pancake anyway. He’d kick her if she didn’t. He likes to read with his feet up, head flat on the seat, to torture her with his smelly tennis shoes that bounce upright beside her shoulder. Likes to? Her sister doesn’t give him much room. And her other sister—

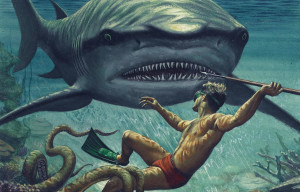

She reads on. The shark is a problem for the teenagers at the beach, a fabulous beach where everybody looks good and hangs out with each other and not with their relatives.

Her other brother is driving. He likes to go fast and when Mom says What are you doing? stopping mid-puff on her fifteenth cigarette, he tries the brakes. The car rocks forward and back, but of course he doesn’t actually stop.

She flattens the paperback and cranes around. Dad’s asleep, his head against the front, passenger-side window. Her sister is singing along to something trashy with her arms raised. Her other sister is peeling a grape into the side ashtray full of her mother’s butts. They stink. She sinks back into the back.

The ocean is calm is what the book swears. But the guy-in-charge isn’t so sure. Underneath lurks—

She stares out the back windshield and the horizon is all wheaty and wavy. She says to nobody, turning another page, I’m sick.

Her sister’s tuning the radio, leaning way over the seat, forcing her other sister to stop singing and sulk. It’s still noisy.

I’m sick, she says again, a little louder, turning yet another page and wriggling her brother’s foot, the one over her shoulder.

What? he says, upside down. He gets annoyed if he has to sit up. Is that book too scary for you? he says, all elbows and red-faced, all the blood in his brain.

No, she says, reading a few more lines. I’m sick.

I’m never sick when I read, he says, unfurling himself back down.

She doesn’t answer him, which is sure to get him ticked. He’s so annoyed he says Mary’s sick! twice, in his special announcement monotone.

Her sister repeats it like a siren: Mary’s sick. Her other sister, still sulking, says Mary’s sick too, but not very loud. Mom says What? Don’t swallow your words.

Is it true? asks her sister, actually turning around. You’re lying.

She sticks out her tongue over her book, then pulls it in quick before her sister can catch it.

Mary’s sick, says her sister.

Okay, okay, says Dad, dragging his head off the window. Stop the car.

Her brother stomps on the brakes and her other brother falls onto the floor with his book.

She gets whiplash but it’s not as bad as her stomach. She keeps her finger in her place and her eyes closed. She opens them when she hears Dad peel out of the front seat and his door slam. At last the wheat stops waving when she looks.

Dad has trouble with the airlock. That’s what they call it: the double hinged back entry that needs a key to open it. Watching him struggle, she takes a long slow breath to keep down the nausea, then the bottom hatch bangs down. She scrambles out but by then, everybody’s out, standing around stretching in the tepid summer wheat-wavy air, the sun beating down and the breeze like an armpit’s. Enjoy, says Dad.

She’s dizzy. That’s the way you get in the back. By the time she touches her way around the car, her brother’s doing cat stretches, Dad’s lighting her mother’s next cigarette, her other brother’s tossing the keys in the air.

Her sister, seeing her gag, says, Well, vomit. Her other sister says, Yeah, vomit! Get it over with. Then everybody starts saying Vomit! And it turns into a chorus: Vomit! Vomit! Vomit!

Would they do this at the gas station? No.

Vomit! Vomit! Vomit!

Only her mother, smoking, doesn’t yell. She’s shaking her empty carton.

It’s not projectile.

Good job, says her brother. Yeah, says her sister, it’s about time. Way to go, says her other sister, disgusted, fanning herself with the door. Her other brother has already lost the keys and he and Mom and Dad go searching for them in the waving wheat.

A big white viscous lump decorates the tufted roadside.

She rests her bottom on the tailgate. She does feel better. Her brother gives her a Kleenex somebody’s already stepped on but she doesn’t mind. She uses it and throws it into the wheat that her sister is pointing at because she has just seen the keys in that direction. Or over there.

Let’s have lunch says her brother quick, to change the subject of the keys now taken away from him. Lunch! Lunch! say at least three if not four others.

She knows that eggs will be involved, deviled, with potato salad and somebody’s gravy over the turkey, all packed in a cooler in the front seat.

Lunch?

You’ve got to be hungry, says her other brother, opening his door. You didn’t bring up that much.

You ate half my pancake, she says. But he almost sounds sympathetic.

She gets back in the car, knowing the time will arrive for food, no matter how she feels.

Dad himself is behind the wheel and when he says Lunch! too that seals it. He says there’s water over here somewhere for a good picnic, let’s look.

Water is not what wavery wheat usually gives up. Dad takes two turns down a long bumpy country road, while she holds the sides of the way back, sour-breath-heaving, thinking about those eggs someone has already almost taken one of, but she manages to swallow and tell her brother about how many people the shark is about to eat and why nobody can escape and if there are any other sharks like that and then there it is: a cow wallow in the middle of the wheat field. The water’s all dark and cool-looking—and there’s a waterfall, says everybody.

Somebody has put a board across the drainage ditch and the water falls. Of course she sees it last. Everyone, even Mom, is already wading in it, knee-high or crotch. There’s even a vista: the view of sixty miles of flat wavery grain.

Her brother stands on his hands, his legs scissoring the air, then he erupts from the water with grass draped on his ears.

Jaws, he says the minute she puts her foot in.

A recent Guggenheim fellow in fiction, Terese Svoboda is the author of six novels, five books of poetry, a memoir, an opera, and a book of translation from the Nuer. Forthcoming this year and next are When The Next Big War Blows Through The Valley: Selected and New Poems, and the biography Anything That Burns You: Lola Ridge, Radical Poet.