We retired, and we bought a house by a lake that none of our friends had ever heard of, in a town none of our friends had ever heard of, in a region of northern New York far from anything, where every low place is the place of a lake.

We retired, and we bought a house by a lake that none of our friends had ever heard of, in a town none of our friends had ever heard of, in a region of northern New York far from anything, where every low place is the place of a lake.

The lake was cool in summer and deep, and we swam in it. All around us were the low small houses of our neighbors and the piney woods, and beyond the woods were the fields where farmers grazed their cattle. The whole town smelled of manure most days. After a while we grew to like it. In a place like this, we thought, where no one knows us, we can be free of the memory of our failures.

We spoke to our neighbors, all of whom had lived their whole lives by the side of this lake and spoke with a strange and musical accent and for the simplest and most familiar things used names we’d never heard before.

They seemed to know the secrets we were keeping from each other and to look at each of us with pity, that we should each be saddled with the other. They seemed to wish that they did not have to see us, swimming in their lake.

For my birthday, which comes in July, my son sent me a kind of miniature helicopter that you fly by remote control. A drone is what he called it. It had a camera in its belly, and the images the camera captured could be played on my computer.

I sent the chopper up over the trees, and I let it sit there. At night it could look into the windows of the houses.

I saw my neighbors in the wildness of love. They contorted their bodies into shapes as strange as the sounds their voices made when they meant to say things like water, elm tree, fish.

I saw the woman who lives next door to us—who is older even than my wife and I and whose husband is dead—arranging russet potatoes in a row on her kitchen table. She stood them up on their fat ends, each exactly two inches from its neighbor on either side. She measured the distance between them with a ruler. Then she stood before them eating mashed potatoes from a steaming pot with a wooden spoon. She was wearing a thick wool sweater but no pants.

Often my son called me up in the middle of the night and left drunken messages on my answering machine, telling me how badly I had mangled his soul, his psyche, how even when he was a tiny child I had been laying the foundations of his future misery.

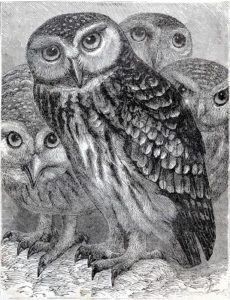

One day I woke to find my drone in a mangled pile on the ground, its bright-colored wires torn out like the guts of some animal and scattered in the leaf litter. I picked it up and carried it tenderly into the house. Somehow its memory was intact, and when I hooked it up to my computer I saw again the quiet houses of my neighbors below me, their kitchen lights gleaming against the furred dark of the woods, the mirrored dark of the water’s surface. If any of my neighbors spoke, I could not hear them. If one of them had picked up a rifle and fired it at my drone to stop my spying, the drone would not have heard it. It had no audio capabilities. When all the lights were out the drone could see no farther than its own lights reached, a few feet into the empty air around it. Then from the boundary between light and dark came a pair of yellow claws. Terrible wings swept into view so closely that for a moment I could see the hollow shaft of each feather glowing in the light, until they swallowed it, and the image went dark.

“Whorl,” my neighbors said.

Or, “Oowrhl.”

Owl, was what I thought they must have meant.

I drove two hours to the nearest Best Buy and bought another drone. I sent it up over the trees and let it sit there.

My wife was hardly ever home any more. She would wake in the mornings at the same time as I did and drink her coffee and say, “I think I’ll go for a walk.” I wouldn’t see her again until the next morning, when I would wake to find her in the bed beside me, fragments of dry leaves tangled among the strands of her beautiful hair.

She said she liked to walk alone in the woods. She liked the quiet. She liked to be in the presence of so much hidden life, so different from her own.

Once I looked up from my desk at the window and saw her swimming in the lake with twenty or thirty teenagers.

“Who were those kids?” I asked when she stood before me the next morning in our kitchen.

“Grandkids,” she said.

“Whose grandkids?”

“Everyone’s.”

When the new drone met the same fate as the old one, I plugged it in and watched the video: dozens of tiny claws this time, tiny wings beating like drops of rain against the camera’s lens.

“Srpews,” the neighbors said. “Sorrows.”

Michael Powers currently lives in Los Angeles, where he is at work on a PhD in creative writing and literature at the University of Southern California. His fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in The Threepenny Review, Bellevue Literary Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and Barrelhouse Magazine.