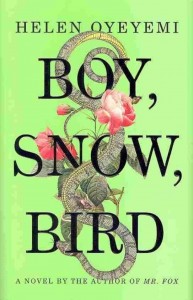

Toward the beginning of Helen Oyeyemi’s fourth and latest novel, Boy, Snow, Bird, narrator Boy Novak Whitman offers us a dictionary-style definition of the word “mirror.”

Toward the beginning of Helen Oyeyemi’s fourth and latest novel, Boy, Snow, Bird, narrator Boy Novak Whitman offers us a dictionary-style definition of the word “mirror.”

mirror: [mirə]

noun

1. A surface capable of reflecting sufficient diffuser light to form an image of an object placed in front of it.

2. Such a reflecting surface set in a frame. In a household setting this surface adopts an inscrutable personality (possibly impish and/or amoral), presenting convincing and yet conflicting images of the same object, thereby leading onlookers astray.

Mirrors and other reflective surfaces pop up constantly throughout Oyeyemi’s novel, taunting and teasing many of her characters. They have the ability to highlight the onlooker’s secrets and inner fears, to bewitch, to entrance, to bring out one’s multifaceted—and, at times, conflicting—self. While mirrors often symbolize vanity, Oyeyemi’s mirrors have depths, personalities, magical powers, even.

Despite her name, Boy Novak is not a boy; she is a strange and intriguing young woman with pale blonde hair. At the age of twenty, Boy runs away from her abusive father (referred to almost exclusively by the title of his profession, the Rat Catcher) and her life in New York City. She steps off of a Greyhound to find herself in the small Massachusetts town of Flax Hill, where she begins to rebuild: she makes friends, finds a job at a bookstore, falls in love with a widowed father and finds herself enraptured by his daughter, Snow.

Thus begins a modern retelling of Snow White: Boy struggles not to become a wicked stepmother to Snow, a child who is swooned over and adored by everyone who lays eyes upon her. While there are moments where readers are convinced that Boy loves Snow more than she does her husband, Arturo Whitman, there is something about the charming little girl that Boy cannot accept. Boy’s skepticism of Snow lurks in the shadows of her consciousness but only briefly comes into the light. Boy tells us that Snow “was like a girl in Technicolor tapestry, sure, sure, but…they’d had a while to get used to her, and acting like that every time they laid eyes on her seemed to me like the fastest way to build an insufferable brat.” Snow never comes off this way to readers, whether as a child or an adult, though Boy’s anxieties never seem unreasonable either.

The book is set in the 1950s, a time in which racial segregation is a norm across the country, and Flax Hill is no exception. Boy’s relationship with the African-American community is complicated. She is able to glimpse at this world separate form her own through the three black students who skip school and spend their days reading in the book store where she works. She befriends them, finds them intriguing, but still holds a fair amount of prejudice against them. She says of Sidonie, whom she invites to her birthday party, “if you saw her without talking to her, she’d make you paranoid in a way that only a colored girl can make a white woman paranoid. That unreadable look they give us; it’s really shocking somehow, isn’t it?”

Here, Boy is making a distinction between black and white, between the “us” and the “them.” And it is through statements like these that Oyeyemi jabs at the reader. We come to identify with Boy, to feel what she feels, no matter how backwards or unspeakable parts of her seem to readers living and breathing in 2014.

And yet, Oyeyemi complicates things, both narratively and morally, for the reader. Every time someone addresses Boy with her name— “Say thank you, Boy” or “You can’t stand for that, Boy”—we’re reminded of our horrific American past, of slavery and Jim Crow. It is a gentle reference, one that you can’t fully convince yourself is intentional until Boy gives birth to her own daughter, Bird, and the Whitmans’ secret is revealed.

Bird is not as white as Snow. Her skin is dark, and Boy’s doctor assumes she has had an affair with a black man, though she has not. Arturo’s family has been passing as white, when in fact, they are light-skinned African-Americans. Only Bird and Arturo’s sister, Clara, who has essentially been banished from the family because of the color of her skin, reveal these hidden traits. As a result, the grandparents continue to dote on Snow and snub Bird and her darkness. Clara tells Boy to send Bird to her so that she can raise her in an African-American community as if she were her own child. Boy takes her up on the offer, but instead of sending Bird, Boy sends Snow.

This action skews our perception of Boy. On the one hand, Boy truly believes that if Snow is away for a while, the Whitmans will warm up to Bird, that they will take her in as their own. On the other hand, she has finally assumed her role as evil stepmother. In a sense, she becomes, at once, both the protagonist and the antagonist of the novel. If mirrors present onlookers with “convincing and yet conflicting images of the same object,” who is the true Boy?

Through moments such as these, Oyeyemi presents us with a handful of blurred lines, those between black and white, between family and outsider, between good and evil, and (in a shocking reveal at the end of the novel I do not want to spoil here) between male and female. The main female characters of this story—Boy, Snow, and Bird—come to exist as liminal beings, ones without definitive identities or places in the world. Boy explains, “you look for signs of a Jekyll and Hyde situation, the good and the bad in a person soften into separate compartments by some weird accident. Then, gradually, you realize that there isn’t a reason, and it isn’t two people you’re dealing with, just one.” It is easy to compartmentalize the complexities of people, harder to take them in as whole.

The mirrors in this novel not only offer us a commentary on vanity and keeping up appearances, but they also give the characters opportunities for self-reflection. Bird doesn’t always see her reflection in mirrors, a detail that demonstrates the lack of belonging she feels within her own family. The same happens with Snow. At times, the reflections seem to act of their own agency, coercing the onlooker to follow suit. Oyeyemi’s mirrors simultaneously highlight one’s secrets and flaws while revealing some hidden desire or truth. In a way, Oyeyemi’s mirrors have more in common with The Mirror of Erised from the Harry Potter series than they do with the mirrors in Snow White or Alice Through the Looking Glass—they reveal inner feelings and longings rather than reaffirm one’s vanity or provide a portal to a different world. “Mirrors see so much,” says Boy. “They could help us if they wanted to.”

Structurally, Boy, Snow, Bird is less complicated, less jarring, less experimental than Oyeyemi’s third novel, Mr. Fox, and the conclusion does not leave us with the wistful, morally ambiguous endings that so many fairy tales do. Sadly, the novel’s ending feels rushed, a “let’s bring the whole gang together” kind of closure that seems inauthentic for these complicated and dynamic characters.

But as in Mr. Fox, storytelling and folklore come to play a huge role in how the characters interact with and come to relate to one another. And Oyeyemi is just as quick in this novel to reference her influences and inspirations as she was in her last. Narratively, there is something wonderfully daring about her self-conscious allusions to Snow White, Alice Through the Looking Glass, and African-American folktales. Boy, Snow, Bird, however, takes the allegorical retelling of folktales a step further. While Mr. Fox uses the tale of Bluebird to comment upon violence against women, Boy, Snow, Bird is able to use the story of Snow White to comment on racism while also connecting it to other manifestations of discrimination, ones that deal with the liminal, those we cannot fit into society’s perfectly packaged box. Because, if we were to look into one of Oyeyemi’s mirrors, what contradictory images of ourselves would we see?

Emily Smith is a writer living in Austin, Texas. She is an Assistant Editor at American Short Fiction and teaches writing to kids with Austin Bat Cave. She has lived in Jordan, Egypt, and Morocco.