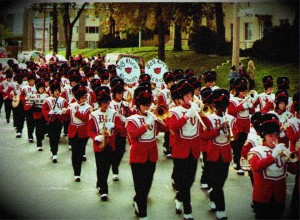

I knew the first time I saw him marching among the other children, this would be the first of a decade’s worth of parades I’d sit through, cheering, waving, catching float candy for later. Turns out I was right. In the past twelve years, Toby moved from Cub Scouts to soccer to marching band, and now here he is, Mr. Drum Major of Mewborn High School, keeping his classmates lockstep in maroon polyester, proud and strong, arm pumping the pole, leading the way down Main Street.

I knew the first time I saw him marching among the other children, this would be the first of a decade’s worth of parades I’d sit through, cheering, waving, catching float candy for later. Turns out I was right. In the past twelve years, Toby moved from Cub Scouts to soccer to marching band, and now here he is, Mr. Drum Major of Mewborn High School, keeping his classmates lockstep in maroon polyester, proud and strong, arm pumping the pole, leading the way down Main Street.

Contrary to what you might think, halftime entertainment for the footballers is just a sliver of what the Marching Wildcats do. These kids play for veterans. They play for charity carwashes and pancake suppers. They play for homecoming parades and Thanksgiving games and every Pelt County celebration in between. They play today, in the heat of July, because we are American. At competition time, they dominate in Raleigh, saving for the grandstand judges at the homestretch their prize-winning “Louie Louie” grooves pitched to a Sousa stride. But they need no prize to play their hearts out. And I never once had to tell Toby the reward is in a job well done. You can hear it now, in each drumbeat, in every hand-blown note.

Today the Marching Wildcats melody energizes the armies of tall-booted baton twirlers and troupes of sturdy Girl Scouts, their green sashes heavy with hand-sewn badges; it thrums for the candy-tossing Ruritans and Future Farmers of America who hang their hand-stitched flags amid the massive crop dioramas on their flatbed trucks. Giant foam cob corn and squash and such. It envelops the Watermelon and Shad Queens and all the other harvest prize beauties who usually sit hip to hip in convertibles with the Homecoming Court. You should see these girls in their gauze and tulle, lovely lipstick smiles and long gloves at ten in the morning, sitting up in the backseats of the handful of sports cars Mary Lanford secures during parade season. For years our Booster Club’s Civic Parade Committee was lush with drivers, thanks to that meticulous list. She’s a powerhouse at home games, prospecting the old coots, leaving scrawled notes on convertible windshields in the parking lots of the Noontime Rotary and Kiwanis meeting halls. It’s harder than you think to find a civic-minded man with enough cash to afford a third car payment but who doesn’t slip away on the weekends to a boat down in little Washington or some second home on the Crystal Coast. And after what happened this spring with Lars Stokes and the Shad Queen, it’s even harder. Our drivers have dwindled to nearly half. I probably don’t have to explain what might have happened for you to catch on to its result, but I’ll leave it at this: girl gone bad, or wild, or whatever. And as embarrassing as it is for their families, I can’t begin to tell what a mess it’s been for everyone else. Last week, Mary Lanford called me in tears, nearly, blaming everything on poor Lars.

“To steal a phrase from our friends in Homeland Security, we are Code Red on the convertible front,” she said. “And it’s not the men who won’t drive these girls; it’s their wives who won’t let them: ‘the next Sissy Saunders in every back seat,’ one told me.” That’s why today there’s four girls to a car instead of three, and why the Cotton and Collard Queens ride with the Ruritans instead of with the misses Tight End and Wide Receiver of the Homecoming Court. “It’s not fair to divide up the ag queens from the rest of them,” Mary Lanford said this morning, clipboard in hand, “but I don’t know what else to do.”

Let Mary Lanford say what she will. Out here on Main Street, the parade looks fantastic. Armies of kids pass with their “Rockets and Whistles” themed wagons and bicycles. Pickup trucks stuffed with hay bales hold the handful of veterans who still fit in their dress uniforms. The men manage to salute for nearly the entire route, too old to walk the half-mile, too dignified to toss candy. Teams of Shriners zoom by in fezzes and funny cars. Unless you’re looking for it, you really don’t notice which frosting-clad beauty sits where. You don’t notice that Lars Stokes’s cherry red 1965 Corvair Monza is gone from the queue, or that Sissy Saunders, the original 2006 Shad Queen, is missing, and the runner-up is waving in her place. Lovely as those girls are, after a while they all start to look alike. But try telling that to Mary Lanford, a former beauty queen herself.

And try telling that to Lars Stokes, who, by all accounts, had responded to Sissy as any unthinking man might. I guess if I had a daughter, I’d feel different—but I still say it’s a shame what happened, and not just because Mary lost a reliable driver or that Lars’s life is ruined on account of a few kisses with some teenage redhead. None of that is really my business. But what is my business is how far downhill the Marching Wildcats pancake suppers have gone since the incident. Lars’ daughter had played tenor sax, and after his wife left him—the same year Toby joined the Junior Marching Wildcats—Lars got involved with the Boosters. He’d tinkered up a bicycle-powered, rotating griddle for the Booster’s monthly pancake fundraiser dinner, said it was something he’d always had the mind to do. I’ll never forget the first time he came to the high school with his contraption in tow. The griddle is the size of a kitchen table made of nonstick aluminum that attaches to a crank Lars hooked up to the pedal part of a bicycle. At the right temperature, that griddle bike can cook sixty fail-free pancakes in a single rotation. At three cakes each, that’s twenty people fed in seven minutes, and after WITN ran a feature, folks as far as Tarboro and Creswell used to drive out just to see the Marching Wildcats Booster Club’s griddle bike pancake maker. At first, all the Booster moms—myself included—asked Lars if we could run the bicycle: imagine losing weight while making pancakes! But Lars would never let any of us near it, said it was a liability. Later we fought—out of his earshot—over who’d get to flip the cakes, on account of the buns-level view the back of the bike afforded. Each month we packed in hundreds of pancake eaters, and at seven dollars a plate, you do the math. Our coffers were fat. The new uniforms were beautiful, and each band member got a $200 subsidy for their trip to the Nationals.

And all was well until this spring, just before May Daze, when Shad Queen went and ruined everything. Like I said, no one knows exactly what happened, because the Sissy is underage and the paper wouldn’t run the real-real story. All that ran was that Lars was arrested for “unlawful conduct with a minor” and he posted a cash bail bond of five thousand dollars. And even Toby tells me that the one who’d started it—whatever it was that got started—was the Shad Queen herself, that it was her mother who caught them smooching in his Corvair after the parade, and it was her mother who called the cops. Lars pled guilty, and he agreed to stay away from all events that involve children. Unfortunately for us, this includes the pancake suppers and all the parades and ballgames. As Mary Lanford said, “there goes our prize Corvair.” And I say, there goes the Marching Band Booster Club’s Cash Cow. And even with her title stripped, Toby tells me, our little Miss Vixen Shad Queen is off, scot-free, a full ride to State in the fall.

No one thinks about the fate of parades or pancakes or the Marching Wildcats Booster Club when she comes onto a man her daddy’s age. And no one thinks about the consequences—let alone the stupidity—of responding to the advances of a child two months shy of being a legal woman. Ever since Lars and his griddle bike were banned from school property, our pancake suppers are chaos. It’s no picnic lugging around one of nine fry pan hibachis and mini-propane fuel packs. And the inconsistency in product that comes with the presence of nine cooks, each of whom thinks she is running the show, is downright embarrassing. I bow out of the cat fight among the Booster moms. I just smile down at my own pancakes, ready with my spatula, counting the days until this is over. Of course, I don’t go around advertising that when Toby’s gone and graduated, so am I. No more pancakes for me. No more parades. Heaven forbid I end up like Mary Lanford, who should have retired from all this three years ago, when her daughter graduated. And we know what happened to Lars, who was probably lonely after his divorce and wanted to make some new friends with his griddle bike. There’s costs to everything we do. Sad as I am to see Toby grow up and get off to college, I’m glad there’s an end to all of this, and I’m especially glad that I’m heading out on the coattails of the golden era of the Lars Stokes griddle bike. Our customers talk with longing about the “old-school” pancakes, which says without saying that the ones we make now aren’t worth the seven dollars. And our coffers show that, ever since Lars’ arrest, our pancake supper profits dipped. As Mary Lanford says, “We’ve got that Hussy Shad Queen to thank for it.” Mary sometimes calls Lars, pretending like nothing terrible happened, to ask if he’d lend or rent out his griddle bike. Or she’ll get me to call so she doesn’t appear too pesky. It’s awkward asking, and every time he refuses. “I’ve done enough, and I’ve had enough, Catherine,” he’ll say, and I can hear the sadness in his voice and I tell him I understand so he won’t feel so alone. And even though I don’t say this to Mary Lanford, I cannot blame him.

Still, it’s amazing the things we do for our children: asking the town’s alleged pervert for his pancake maker. Or standing on the side of the road, camera in hand, waiting to take the perfect shot. Sure, I’d rather be on my couch with a book, or crocheting afghans for the church fair. And while my friends tell me that I could easily find another man to keep me company—and for full disclosure I’ll admit that until recently Lars had been on their short list—I keep to myself ever since Toby’s daddy died. Toby was just four; old enough to know his daddy was gone but too young to understand a heart attack. Thank God Toby and I still have each other.

And now here he comes, leading the thrumming pack of drummers, the kids holding the horns and the xylos, hoping to God the horses keep their sphincters in check. Rule is, you march right through, no matter what. And Toby looks great. He’s earned this moment—at the center of the entire parade, keeping pace with his baton for all the little ones in the back. He’s so intent on keeping time he fails to catch my eye as he passes by, even though I yell his name when I click the shutter. The wave of drums rattles and surges and then it’s over. In the fall he’s off to college, and all this pancake and parade business, Mary Lanford and Lars, will be a thing of the past. I rise up on tiptoe and lift the camera above my head, in Toby’s direction, hoping the frame will capture this last glimpse of him, the back of his high stiff hat, and the marchers who follow in his wake.

Erica Plouffe Lazure is a graduate of the Bennington Writing Seminars and lives and teaches in Exeter, New Hampshire. Her fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern #29, Flash: the International Short-Short Story Magazine, Greensboro Review, Meridian, Litro, Microliterature, Monkeybicycle, Booth Literary Journal, and elsewhere. A short collection of her flash fiction is forthcoming in an anthology, Turn, Turn Turn, by ELJ Publications, and she is hard at work on a novel. She enjoys hula hooping and playing guitar and singing in the Dog House Band. She can be found online here.