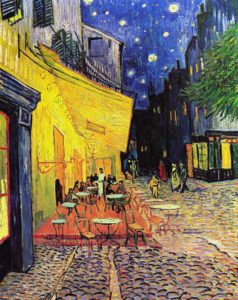

We’ve already tried everything. We tell the waitress to bring rolls, wine. Meanwhile we’ll decide what we want to order. This is our favorite restaurant. It’s the only restaurant in town as far as we’re concerned. The atmosphere is exquisite—carpet with hunting scenes, dark wood. The mayor and his cronies sit nearby, tearing apart their steaks by candlelight and spilling juice on their ties. I wave. And there’s the guy Lynn always goes on about, the stiff cowboy type who can’t move his neck. The waitress brings the rolls and the wine. We send her away again. She returns at intervals to see whether or not we’ve made a decision. We haven’t. She fills our water glasses. After a while, she hangs back a few tables.

We’ve already tried everything. We tell the waitress to bring rolls, wine. Meanwhile we’ll decide what we want to order. This is our favorite restaurant. It’s the only restaurant in town as far as we’re concerned. The atmosphere is exquisite—carpet with hunting scenes, dark wood. The mayor and his cronies sit nearby, tearing apart their steaks by candlelight and spilling juice on their ties. I wave. And there’s the guy Lynn always goes on about, the stiff cowboy type who can’t move his neck. The waitress brings the rolls and the wine. We send her away again. She returns at intervals to see whether or not we’ve made a decision. We haven’t. She fills our water glasses. After a while, she hangs back a few tables.

We really have tried everything. We’ve attempted middle-aged parkour, taken polka-dance lessons in a barn, experimented with container gardening and vermiculture. Still, in marriage little things bother. Lynn cringes every time I clean the rim of my risotto dish with a thumb. I can’t stand how long it takes her to consume even the tiniest endive salad. She’s lost her taste for our baths together because of my farts. When she parks her compact car in the garage, she never leaves enough room for mine.

We are considering our options. She enjoys the seared ahi tuna and will sometimes go with that and a caprese salad for her entire meal. But it’s winter out. It doesn’t work. I’ll often order butter-poached lobster tail or, when stressed, the pepper jack cheese curds. Thing is, I’ve put on five pounds since Thanksgiving, which we always spend in the same Midwestern hamlet thirty miles away, around the same double-leafed table, crowded with the same faces, and featuring starchy lumps. When Lynn was a girl growing up in southwestern Minnesota, she wanted to sing arias in Milan, and now she keeps books for ranchers. I always wanted to be a high school history teacher, so I went to Marshall and majored in history education, then did some substitute teaching around the area, and eventually became a high school history teacher. Sometimes I wonder if I made the wrong decision by doggedly pursuing my childhood dream.

The waitress creeps around; I send her off. “Two more minutes, please.” That’s the estimate I always give, like punching snooze on an alarm clock. Her eyebrows seem painted on in expressive arcs. I think she’s a college student, and she probably has homework to do. They still do homework in college, don’t they? Last year when they put the teres major on the menu, Lynn ordered it because it sounded like a musical key. It was the same shoulder muscle I pulled last spring, except on a cow. The injury knocked me out of the racquetball league and into my chair. And I put on six pounds. The steak came overdone and slathered with the chipotle-pineapple glaze Lynn had told them to leave off. She never ordered it again, and I see it’s no longer on the menu.

It’s always hard. I’m trying to decide between the curry-rubbed rack of lamb and the fire-roasted-jalapeño-and-cheddar burger. Lynn probably thinks she married down in matters of taste. I like burgers, but I don’t order them unless I’m eating alone at lunch. In 2014 we tried ordering a few items and sharing, despite the extra-plate fee. That made meals interesting for a while, each of us trying dishes we normally wouldn’t order. I sometimes got frustrated if the portions weren’t equally divided. Too many peas on my side, not enough of the aioli. We stopped sharing, I think, because both of us were secretly half-disappointed every time.

The waitress hasn’t come back for a while. It’s spitting snow in the alley outside our window. It will accumulate overnight, and in the morning the entire world will take on a white cheer. The bushes will wear Russian caps. Winter always makes me hungry. The bleak months are a time to festoon the organs with fat. I need to visit the men’s room, but I don’t want to miss the waitress this time.

The mayor and his cronies are looking at dessert. I think I may have sent her away too often. I try to signal a busboy, but he doesn’t notice me. When Lynn clicked on my dating profile nine years ago, and we came here because it was the only real restaurant in town, I remember wondering if I could ever love someone who enjoyed doing taxes. Of course, I was pleasantly surprised. Because here we are.

Most of the rolls are gone and all the honey-infused butter. Lynn needs a refill . The cowboy’s settling up, and I bury my face in the menu, which by this point I know all too well, its gilt-edged laminate. This menu: always changing yet never satisfying. You’d think if you could sit across a sturdy table from the person you’d selected, a life partner, the candle flame streaming upward like good luck, if you could settle into the same cushioned seat each Wednesday, have your crumbs scraped away by a figure of meek attention, and all the while sample the world on your tongue—the green flower of oysters Rockefeller, paella with the salt of the Mediterranean still crusting each shrimp, elk backstrap atop garlic mashed russets—you’d think that then you’d have everything you needed and could set the menu aside. But it’s just another anniversary at our favorite restaurant, another meal we’ll order and consume with small satisfaction—a piece of meat ever divided and divided between knife and fork, down to a brown button. My bladder shoots pains into my groin. Where is the waitress?

She appears out of nowhere. Just now she strikes me as the sort who cannot commit to a long-term relationship. Sweat has slicked down a lock of her neck hair. A tiny hole in her lip reveals it is pierced, although she wears nothing in it. I suspect facial jewelry is forbidden here. I can’t imagine her getting married for a long time yet. Being a waitress must really turn her off of the whole thing. I’m in pain. I speak across the white tablecloth to Lynn, who hasn’t noticed that the girl is back.

“I guess I can be ready if you go first.”

Peter Grimes is an assistant professor of English at the University of North Carolina—Pembroke, where he teaches creative writing. He also serves as the editor of Pembroke Magazine, an annual journal of fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry since 1969. Peter’s fiction appears in journals such as Narrative, Mississippi Review, Fiction International, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Memorious, Sycamore Review, and others. Visit his website at www.peterjgrimes.com.