I. To Begin, a Note about Pleasure

A few years ago, the late James Salter was honored at the annual F. Scott Fitzgerald Festival with a prize in Fitzgerald’s name. During his keynote address at the award ceremony, Salter said something that was stupefying in its simplicity: reading, he said, was among the very greatest pleasures in his life. Perhaps that’s not a surprising sentiment for a writer so notably interested in pleasure, especially the pleasures of food, drink, travel, language, and sex. Those interests had earned Salter a reputation as an aesthete, even a highbrow. Still, it’d taken me until that moment—in my thirties and having worked for a decade in publishing and more than a decade of writing my own fiction—to think of reading primarily in terms of pleasure.

Earlier in my life, it’d seemed to me that to consider fiction in terms of how it gave the reader pleasure was somehow beside the point, that reading for pleasure wasn’t an appropriately elevated way of understanding novels and stories. That strikes me now as haughtiness, a self-important way of framing my own readerly pleasures in order to make them defensible to others by casting them as academic pursuits. It’s probably not surprising that this attitude was born of theory-heavy college classes. Of course, there’s plenty of pleasure to be found in theory, too, for a certain kind of reader, and for a long time, I badly envied that kind of reader. I wanted to be that kind of reader, though my theory chops were never very good.

Salter, then already in his eighties, proclaimed a basic truth about his own motivation for reading and writing that was aphoristically simple. It was a huge relief to hear it. It was the first time since being a teenager that I felt that reading merely for the pleasure of it (and writing in an attempt to evoke that pleasure in others) was worthwhile, in and of itself. There was no scholarship to note in order to defend a piece of writing I loved. If pleasure were reason enough for Salter to continue reading, I reasoned, then certainly, it could be enough for me.

As a teacher and an editor, I don’t get to read purely for pleasure as often as I’d like to, though it’d be dishonest to say that pleasure-seeking doesn’t play an enormous role in my teaching and editing. While pleasure may not be sole navigational star guiding my editorial and pedagogical sensibilities, it’s certainly the brightest of them.

So, when I was asked this spring to give a talk at Grubstreet’s Muse and the Marketplace conference in Boston, I couldn’t help but frame my talk around readerly pleasure. That’s not what I was supposed to be writing about; I was supposed to talk about writerly pitfalls that should be avoided when submitting work to literary journals, but coming up with a list of pitfalls was a tall order. Were these supposed to be major sins or minor ones? Structural issues or issues of content? Were these to be my own pet peeves or a more general list of things to be avoided when writing?

A few weeks before the conference, with just a handful of notes written and sweating it a little, I realized that part of the problem of developing a list of literary pitfalls had to do with my own desire to derive pleasure from my reading—all of my reading, including the things I chose to read because they interested me and the things I needed to read because reading’s part of my job. In my teaching, in my work as an editor at American Short Fiction, and in my personal reading, I’m almost always attempting to read for pleasure. This poses an obvious problem when trying to write a list of writerly dos and don’ts: What in this life is more subjective than an individual’s experience of pleasure? Is it fair for an editor at a magazine to use their subjective experience of pleasure as the measure of a story’s worth?

Identifying a top ten list of prose pitfalls is further complicated by time. As I’ve aged, my interests and proclivities have changed. So, too, have trends in publishing and readerly interests. A story that might’ve grabbed me five years ago could strike me today as ground that’s too well-trodden to be of much interest. Conversely, a piece that might’ve once struck me as obtuse, stuffy, or otherwise a-bridge-too-far could, today, bring me to tears. Shameful as it is to admit, in college I read two or three Alice Munro stories and thought her too quiet for my tastes. Today, I find myself very moved reading those same stories I’d once found plain. I’d read Paul Auster feverishly as a teenager and college student, but today, when I look back on the happenstance in Auster’s novels, it strikes me as too unlikely to engage me as it once did.

While my experience of a work of fiction certainly isn’t an objective measure of that story’s merit (is there any objective measure of any art’s merit?), it’s true that most editors and most writing teachers I know are invested in the work they do because of the potential to find pleasure in the endeavor of reading. Accepting or rejecting a story is not a matter of measuring a story against some universal yardstick of taste; that I’m aware of, no such yardstick exists.

Still, it’s true that delight, surprise, a beautiful turn of phrase, a joke that lands, a character that stands out, a vivid narrative passage, or a memorable image are often the elements of a story that make me feel like I’ve understood something as it was intended and that give me the decidedly pleasurable sense that a writer has reached out over a great distance and drawn the words exactly as she’d intended to onto the very surface of my brain.

II. A Little on Pain, Rejection, and Hypocrisy

Attempting to boil down the reasons an editor might reject a story seems like asking you to list your worst personal attributes: you know what you believe they are, but giving them voice is awfully uncomfortable.

It’s uncomfortable because attempting to articulate my own subjective reasons for rejecting a story leads me to wonder if any of my own work would pass muster. Admittedly, prior to working at American Short Fiction, first as its web editor and now as its managing editor, I’d had two stories rejected by the magazine. There you have it: one of my most terrible writing-related secrets. Even I, who now work here, couldn’t place a story in ASF.

If I’m going to give advice to other writers about what they should or should not do in their fiction prior to sending work to journals, then I’d be a fool not to hold myself to those same standards. Worse than a fool, I’d be a hypocrite. Yet here I am, looking at my notes from that talk in Boston alongside a couple of my own short stories. There are contradictions between my advice and what I’d managed to accomplish in my own work, and they make me cringe. But then, we should cringe a little at our earlier work. Maybe that’s the one abiding measure of a writer’s growth. This is one thing I tell my students, anyway.

Thinking of writing in terms of pleasure has given me an opportunity to better and more accurately describe what I find good about stories. In attempting to write a list of writerly pitfalls, I found it disorganized and more than a bit petty to simply list what I felt was bad in the short stories I disliked the most. So, instead, I asked myself what was great about pieces that I’d enjoyed and spent a lot of time thinking about how those moments came into being, what a writer had done in order to grab my attention and to hold it.

Even in stories that were rushed or riddled with typos or populated by thin characters, there is often something pure to admire: a line of dialogue that’s perfect and subtle, a description of a childhood bedroom from the eighties that’s so apt and clear that, for a second, you can’t help but remember your own collection of M.U.S.C.L.E Men or your own long forgotten Lite-Brite. More often than you might think, even a clunky story has a sentence or two, or a paragraph, or a scene that’s arresting or lovely. Most editors can see, in those moments, what the writer saw and understand why that writer submitted the story in the first place. A beautiful scene or a memorable character is almost never enough, on its own, to justify publishing a story, but when you consider how damned difficult it is to write a good scene or to create a truly memorable character, you can’t help but feel abiding respect for the work and its creator.

A big part of an editor’s job is to see where a story succeeds and to encourage those kinds of successes, even when (perhaps especially when), you don’t accept that story for publication. In attempting to write a list of pitfalls, then, I found myself mostly wondering about the common ideas, plot elements, stylistic moves, or character traits that detracted from my ability to find the work pleasurable in spite of the good and interesting turns that a particular story took.

Obviously, there are any number of reasons a story might be rejected by a journal, but before I get to the list I compiled for that talk in Boston, I’ll go ahead and cop to my own long history of literary rejection. I’m doing so not so much to earn your pity (though I’ll take it!), but because most editors I know have also been on the receiving end of editorial advice and rejection. Most of us have long Submittable cues, stories of near-misses, and the occasional story of success.

I’ve published seven short stories in my life, most of which took a very long time to write and an even longer time to find a home. This is not so uncommon. Among writer friends, many have hard drives filled with drafts and partial drafts, rejected stories, novels that never gelled, books that never sold.

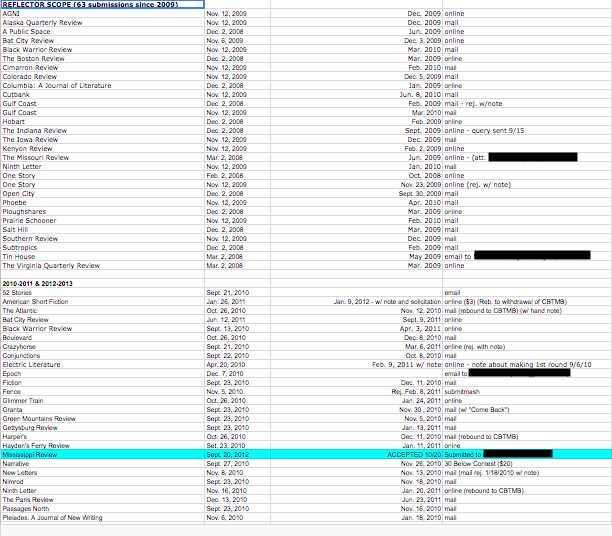

For years, I kept track of my submissions in a spreadsheet, with the story titles in bold and columns for the magazine’s name, the date of submission, the date of response (mostly rejections), and any related notes (was it submitted online or by mail? Did it get a personal rejection or a form rejection? Was there a particular editor who replied?).

One story called “Reflector Scope” was submitted to sixty-three journals over the course of three years before it got accepted. It was another year and a half before it was published. A story called “Come Back to Me, Baby” took a whopping eighty-nine submissions and nearly five years to find a home. The quickest turnaround happened when an editor heard me read a flash piece one April and asked if it’d been published (it hadn’t). He put it out in his journal that October.

All of which is to say: each of those rejections stung a little, but most of them didn’t sting badly. One advantage a writer who works as an editor has is that rejections tend to smart a little less because we know that the ratio of rejections to acceptances is daunting. For the most part, my work in publishing has taught me that you have to move past rejection quickly. What’s the alternative? To put the story away? To quit? To be paralyzed by rejection slips? To be so wounded by rejection that you apply to law school (I shudder at the thought)?

This brings me to another thing I tell my students about writing: perhaps the only real way to “lose” is to quit. If writing’s important to you, regardless of whether you find success (or the kind of success) you want, don’t quit. Do. Not. Quit.

III. I’m Getting to It Now

Which brings me back to that conference room in Boston. While I had my doubts about usefully giving a talk called “Don’t Get Stuck in the Slush: 10 Pitfalls to Avoid When Submitting to Literary Magazines,” I had no doubts at all about the value of regional writers conferences.

The (admittedly useful) morass of AWP aside, the regional conferences and festivals that I’ve attended in Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Brooklyn, DC, Austin, and Boston have given me the opportunity to meet writers from across the country, usually in venues far more personal than the fluorescently lit, terrarium-like conference centers of AWP. It’s also true that many writers who attend regional conferences don’t necessarily come from MFA programs or the world of publishing. They have day jobs. They write at night and on the weekends. They’re librarians, historians, pharmacists, teachers, doctors, retirees—and, yes, lawyers. Many of the people I’ve encountered are engaged in community workshops or writers’ groups of their own. Some are in book clubs. Some are much further away from writing circles. Which is to say: attending conferences like the Muse and the Marketplace or Barrelhouse’s Conversations & Connections has allowed me to encounter work that might not otherwise cross my desk. The list of pitfalls I ended up writing is intended to benefit those writers who are already in writerly circles (those enrolled in MFA programs, or who have gotten fellowships or attended residencies, etc.) and those who are not.

Once I’d written the list of editorial pitfalls, I realized that I also had to prepare some opening remarks about the list and about why, more generally, I felt that fiction writing was an important endeavor. What I ended up writing had a lot to do with the alphabet and with dinosaurs. Here are those thoughts, more or less as I delivered them in Boston.

IV. (A Slightly Modified Version of) A Talk about Dinosaurs and the Alphabet

The year I turned seven, I saw The Land Before Time, an animated feature from Don Bluth, the acclaimed artist and director who, a few years earlier, had made The Secret of NIMH (1982) and An American Tail (1986) and who, a year later, would release All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989).

It’s only a small exaggeration to say that the aesthetics of my childhood were defined by Don Bluth, Unsolved Mysteries, MC Hammer, Saved by the Bell, and about two dozen R-rated movies that I was too young to reasonably view but that I got to watch anyway because my grandmother had cable and, as the youngest of six siblings and one of fourteen first cousins, my parents had given up trying to shield me from the entertainments enjoyed by the older kids in my family.

This was 1988, the era of Platoon, Terminator, Robocop, Predator, Hamburger Hill, Full Metal Jacket, Labyrinth, Stand by Me, The Lost Boys, and something called Alien Warrior—all of which would, in time, frighten or titillate me in some frankly confusing ways. Incidentally, Alien Warrior was so awful that I feel compelled to quote the Rotten Tomatoes synopsis of the film here:

A space alien martial arts master visits a tough inner city neighborhood and helps the good people there find hope and better lives while simultaneously ridding the streets of all bad influences in this low-budget outing. Also released as King of the Streets on VHS, whose cover leaves out any mention of the sci-fi elements as well as audaciously stating that it stars Larry Fishburne (which it does not).

The movie was so bad that thirty years later, it’s become the high-water mark of terrible films in my family. When my seventy-seven-year-old father is watching something he thinks truly sucks, he might look over at my mother and ask, “Are you ultimate evil?” a line delivered in Alien Warrior to neighborhood gangsters by the movie’s alien hero.

If, at least in my mind, Alien Warrior represents the nadir of eighties movie awfulness, then The Land Before Time represents the zenith of eighties movie excellence. The year it came out was also the year that my parents had taken my brothers and me to the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles where I had seen dinosaur fossils that, as those R-rated films had done, delighted and frightened me.

The prospect of seeing these long-dead beasts draped in animated flesh and enlivened with voice was irresistible to my seven-year-old, Hammer-pants-wearing, bowl-cut-sporting, friendship-bracelet-donning self. But not even the scariest moments of Unsolved Mysteries—when Robert Stack would step out of the low, violet fog in his long Macintosh coat and describe horrendous home invasions and whole-family massacres—could match the upset I felt during The Land Before Time.

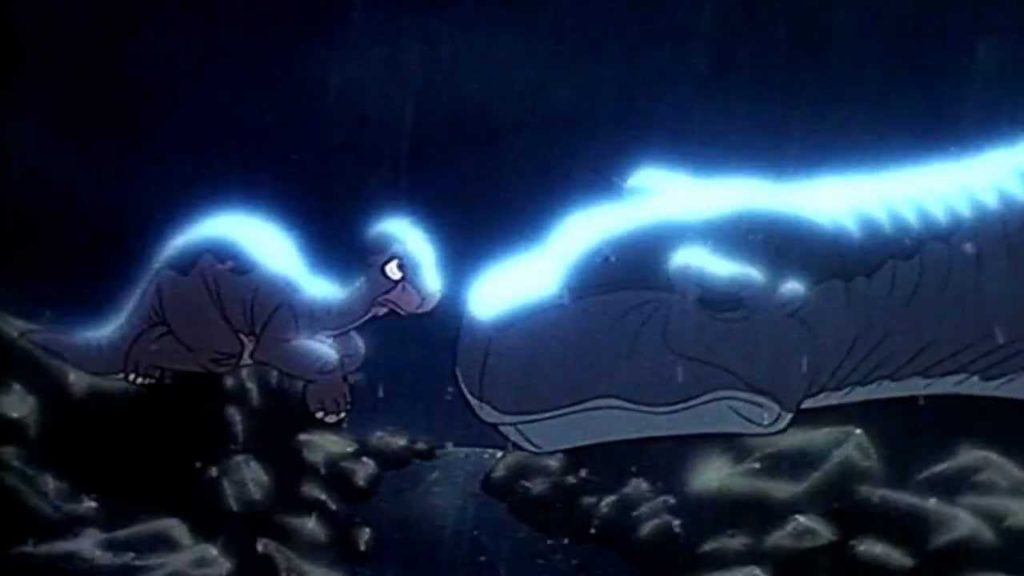

If you recall The Land Before Time as vividly as I do, you’ll remember that, early in the movie, the film’s protagonist, Littlefoot, is protected during a Tyrannosaurus attack by his devoted mother, a peaceful, leaf-eating “Longneck” dinosaur. In protecting her offspring, she is mortally wounded and, following her death, Littlefoot collapses and weeps in the swimming pool-sized footprint she leaves behind.

Littlefoot was inconsolable in that moment. So was I.

It was then, in the winter of 1988, while watching a fictional cartoon dinosaur named Littlefoot mourn his mother that I understood that, someday, short of suffering some fatal tragedy myself, I’d have to mourn my own parents.

I know that my understanding of mortality occurred earlier than the winter of 1988. By then, I’d already seen my paternal grandmother in a casket, and I’d already seen animals on my parents’ little property die. Collecting eggs from our hen house one morning, I wanted to see what would happen if I broke an egg, but I’d pulled it from one of the upper nests where, unbeknownst to me, fertilized eggs were incubating. In breaking the egg, I killed the under-developed chick inside, and I cried at the sight of its tiny, wet body.

Oddly—and this is difficult to admit—that chick was somehow less horrible than the death of Littlefoot’s mother. My mother and father had consoled me at the death of the chick, but even at seven, I had too much pride to ask for comfort following the on-screen death of an animated dinosaur. Really? I thought to myself. I’m crying over a dinosaur? Also, the death of the chick was in my hands. I could take responsibility for it. I could feel guilt, which was evidence of my own relative agency. It was also evidence of my goodness, and of my ability to understand that I’d done something wrong, which was reassuring because, within that understanding was a parallel knowledge: that if you could identify where you’d gone wrong, you could avoid doing so in the future. I’d killed that chick, but I could commit to never doing something like that again. But what could I do about the inevitable death of a parent? Not a thing. I could resist it all I wanted, and I could avoid thinking about it, but I knew then that, some day, I’d be lying in my own dead mother’s footprint, paralyzed by grief.

This is, of course, a relatively straightforward description of how pathos operates. Pathos, that rhetorical mode familiar to people who’ve taken a composition course, is surprisingly easy to misunderstand. It’s not the act of implanting feelings in others via the conduit of art; it’s the arousal of pity, sympathy, tenderness, or sorrow that are already extant in the listener, reader, or viewer.

I’d been aware of death prior to killing that chick just as I’d been aware, prior to viewing The Land Before Time, that everyone dies. But I hadn’t felt the full weight of that knowledge until I’d seen it so dramatically and movingly depicted. It’s a common contention—one I share—that the power of art resides in its ability to provoke such feelings and, in doing so, to move us beyond distant and abstract notions of the world around us and toward an understanding of the world that’s felt. It’s the difference between knowing that, one day, my wife will die and lying in bed next to her at night and futilely trying to resist the fact. It’s the difference between soberly reading about black holes on the internet and suddenly imagining what it means to live in a universe in which these epic monsters eat everything, even light.

But how do we, as writers, manage to make readers feel rather than to merely imagine? How do we communicate authentic sentiment in a way that provokes a reader into feeling without leaving that reader feeling entirely manipulated?

The answer, I think, lies in the language we use, which brings me to a quick note about the alphabet:

Humans are far from unique in our ability to communicate through sound. Even the dinosaurs likely had complicated vocalizations similar to those of modern birds, which sing to attract mates and to sound alarm. Howler monkeys, too, may hoot to warn of an approaching jaguar, just as the jaguar hisses to ward intruders away from its turf. Even my own cat, Steve Brown, squeaks like a hinge when she’s hungry and growls if you play with her too vigorously.

Humans aren’t even the only animals that communicate using a symbol-based alphabet. Some nonhuman primates have been trained to use a written, semiotic language called Yerkish, which includes pictographic symbols (lexigrams) and grammatical standards for how to combine them. These lexigram keyboards, used by primate researchers and their great ape subjects, are nuanced and beautiful. There’s some good further reading on this from the Great Ape Trust and in this episode of Radiolab, in which a bonobo named Kanzi (who uses a lexigram keyboard, sign language, and vocalizations to communicate) warns a researcher that he’s going to bite him, proceeds to do so, and then, eight months later, offers the researcher an apology for having bitten him. How different is Kanzi’s remorse, ultimately, from what I felt after having killed that chick?

When it comes to English-speaking humans, though, we’re dealing with a phonetic language and a mere twenty-six symbols with which to compose several thousand commonly used pieces of vocabulary. Of course, there are many, many more words in English than this, but on any given day, we’re painting with a surprisingly limited palate. (This vocabulary test, produced in association with the University of Wellington, is telling and entertaining, if also a little deflating, at least for me.) Yet, even with this relatively small set of tools, we’ve got an incredible range of stories and films and novels, each so different from the next, and each the product of an individual imagination.

Because we’re human and because we have that relatively small linguistic toolset—and because we live, in the most general way, among one another and under similar conditions and experience many of the same sensations and share many of the same concerns—we also tend to make many of the same assumptions about what art can do or be. In making these assumptions, we grow blind to the clichés in our own work, and we often stop seeing how our own sentiments and ideas are common or derivative. Sometimes, we can’t even understand when our language is reductive and hurtful.

This may be a second arena in which the professional editor has a bit of an advantage over other writers. Because we see so much work in draft form, we also tend to develop a barometer for where things are going and where, frankly, writers make the same assumptions and missteps. I say missteps here for lack of a better term; you could call them oversights, mistakes, clichés, whatever. For the purposes of the event in Boston, we went with “pitfalls.” What we’re talking about are patterns of writing that are so ubiquitous as to become invisible in the eyes of the writer. That they’re evident to me may only be because I read submissions to American Short Fiction nearly every day. More rarely, a writer will have an idea that’s just plain awful or misguided. They’ll want the story to have all been a character’s dream. Or they’ll not reveal that the protagonist is actually an animal until the story’s final page. They’ll attempt a joke that’s just not funny—or even one that’s offensive.

Less often still, there’s work that is motivated by a desire to cause harm: to scorn or to advance a fundamentally bad agenda. Once, at a conference, a writer asked if I’d look at the first chapter of her memoir. In the first two pages, it was apparent that the child protagonist felt curiosity, fear, and hostility toward the African-American woman who’d helped raise her. As I read the chapter, there was no reflection upon the relationship between this thinly drawn nanny and the child, no acknowledgment that the nanny wasn’t privy to the civic, social, and economic status that the writer’s family enjoyed. By the time I’d gotten to the paragraph in which the writer described having deeply desired to ride the nanny’s backside like a horse, I set the pages down and handed them back.

It was horribly awkward, and the writer wanted to know why I’d stopped reading. I told her that you could write a memoir in which you described once having been fascinated by and fearful of racial difference, but that you had to show the reader that, somehow, you’d grown in the sixty or seventy years that had elapsed between then and now. You had to show the reader that you weren’t hateful. You had to show the reader that you were describing your nanny in animalistic terms out of ignorance, and that if a reader was to find any value in the work, they’d have to be sure that the woman writing this memoir had become far better, kinder, and wiser than the ignorant girl she’d once been.

“But I wasn’t ignorant. I was a little girl, but I wasn’t ignorant,” the writer insisted. Then, leaning in closer to me, she said, “You know, they even smell different than we do.”

It was clear then that the writer was only writing to affirm her racism, or perhaps even to be praised for it. To find a reader who’d nod along in agreement with her despicable notions. I handed her pages back to her and said, “I’m sorry, but this just isn’t for me,” before adding, “this isn’t for anyone.”

It was, hands down, the worst experience of my life as an editor. I walked away, leaving her sitting there with her pages, which offended her. She complained to other writers at the conference about me. In retrospect, I should have torn the pages up, thrown them in the trash. I should’ve told her to do the world a favor and never write another word. Perhaps the worst part of the experience was this: I’d told her that her pages weren’t for anyone, but that’s not quite true. I imagine there are plenty of people who’d read her memoir without a giving much thought to its racism, or readers who’d write the author a pass for it on account of her age. Worse, there are those who’d think she didn’t go far enough in describing how alien and horrible her nanny was. If I had a time machine, I’d go back to my childhood and dissuade my kid-self from watching Hellraiser (that particular R-rated film was a bit too much). Then I’d go back to that writers’ conference and tell that woman to burn her manuscript.

Readers know the difference between writing that aims to depict the worst of humanity (our racism, sexism, classism, our murderous ability and our depravity, our ability to abuse) and endorsement of those ills. Depiction and endorsement are not the same. In my reading life, I have reveled in wonderful depictions of absolutely terrible people, and I have cringed at work that aimed to uphold or promote the very worst that we humans have to offer.

V. Finally, the List: Ten things to Consider Prior to Submitting a Story for Publication

Here’s the slightly edited and amended list of ten story elements that I’ve been thinking of a lot recently, primarily because they pop up time and again in work I’m reading for American Short Fiction. This list is by no means definitive, nor is it a representation of what other editors at ASF may be thinking of or looking out for. This list is purely subjective, in other words, and it’s also constantly changing.

But, for what it’s worth, I hope it’s useful in some basic way to see what one editor at one journal is thinking of during the very hot summer of 2018 as he considers which stories he thinks the journal he works for should publish.

Some of the items on the list are probably familiar to you. Some are structural or grammatical in nature. Others attempt to get at the stickier issues of depiction vs. endorsement, the subjective nature of beauty, and the question of how much is too much when your characters are suffering. The items are listed in order of their relative moral weight. This, too, is subjective, though I doubt anyone would think a question of adjectives is quite as weighty as a question of cultural appropriation.

Ten Pittfalls to Avoid When Submitting Your Short Stories to a Literary Magazine, Ordered Roughly in Order of Their Moral Importance, from Least Significant to Most:

1. Avoid adjective, adjective, noun constructions.

An obvious one, perhaps, but these are everywhere:

The big, bad wolf;

The cute, fat baby;

The big, blue house;

The deep, dark wood;

The little, blonde boy;

The frustrating, overused construction;

The stupid, lame story; etc.

I’m no anti-adjective snob, but choosing one apt adjective is almost always preferable to combining two that are less memorable or specific. Perhaps even string together five or six or seven adjectives; that can be surprising and fun. But avoid the monotony of the adjective, adjective, noun construction.

2. Reconsider beginning your story or chapter in dialogue.

This is an old saw, but bear with me. In my experience, a writer doesn’t typically need to start with a line of dialogue and, often, doing so runs the risk of alienating a reader from the story’s opening. By providing a reader with some context—some bit of narration that examines the setting or characters—you’ll more firmly establish the rhyme and reason behind a particular line of dialogue.

Even if a line of dialogue is expertly crafted and beautiful, I’ve found that, almost always, the line can be delivered to better effect when it comes after a short narrative passage establishing some of the basics of the story’s opening scene (details of place, physical character traits and/or physical position, etc.). Because narrative passages can move through time and space quickly and scenes are fixed in time and space, I find myself more easily and naturally led into stories that begin in a narrative passage that provides some context for the scene rather than beginning in the middle of a scene, fully unaware of who the characters are, where they are, what they’re doing there, and why they’re saying what they’re saying.

It’s also true that attempting to include expository information in dialogue is often really wonky, as in: “Oh, Gillian! I wasn’t expecting you, given that you’ve recently had surgery. Is Kyle, that dashing husband of yours, with you? No? Don’t tell me he’s so drunk again that he can’t attend his own nephew’s birthday party!”

Narrative passages more naturally and subtly allow you to deliver basic, grounding information to readers, thus avoiding really clunky exposition delivered in dialogue.

3. Avoid filler phrases and empty words.

More than just reading through your work and excising clichés (are your protagonist’s eyes really gray? Is she really effortlessly beautiful?), our speech and writing is peppered with helpful words and phrases that quickly and effectively communicate meaning. In our day-to-day lives, that’s all well and good. Most of us speak much more frequently than we write, and most of that speech should probably be quick and effective.

But when it comes to fiction, our prose should do more than merely communicate information. At least in theory, we’re making art, and we’re crafting art with an extraordinarily limited palate, so each sentence, word, and phrase counts for a lot. Don’t waste time or energy (or your reader’s time or energy) by crafting sentences with words that, while effective in speech, fall flat on the page.

These include the words just, like, thing, so, obviously, clearly, and the phrases of course, the fact that, for instance, for example, and you know. These might propel a draft forward, but they can often be edited out and or sharpened in revision.

While not every sentence in your work must be little nugget of prose genius, I think we owe it to our stories to make our writing definite rather than general, sure rather than waffling, clear rather than murky, and beautiful rather than plain.

There are exceptions here, especially in dialogue. If you’re writing naturalistically, then characters probably will employ some of these words and phrases in their speech. Ultimately, the writer should be aware of when these phrases are being used intentionally and when they may be employed thoughtlessly. Aim for intentionality and to excise thoughtless usage.

4. If you use ellipses, be aware of what they connote to readers.

When drafting, it’s not uncommon to drop an ellipsis into the prose when something is dragging or when we, as writers, are trailing off in thought. In my own drafts, I tend to use them when I know I’ve got to return to a passage and add detail.

Perhaps we’re just trying to get from the really hard scene we’re working on to the fun passage we’re excited to write next. In any case, in the most basic way, an ellipsis is used to indicate an omitted word or thought in a narrative passage, or an ellipsis can be used to indicate, in dialogue, that a speaker is trailing off or going silent.

An ellipsis may be used in a narrative passage when an author or narrator is eliding or omitting information (keeping it from the reader) or in a scene when one character is trailing off.

For interruptions of thought (in narrative passages) or interruptions in speech (in dialogue), it’s become much more common to use em-dashes (“—”) rather than ellipses. Ellipses imply trailing off or omission; em-dashes connote interruptions of thought or speech.

5. No “trick” endings. Yes, this still happens, and, yes, it still mostly stinks.

A few years ago, a colleague was reading a student’s story with language so surprising and bright and strange that my friend was elated upon reading it. The metaphors were fresh and enticing. The characters were somewhat illusive but were thoughtfully imagined. The story was philosophical and lyrical. The last line of this bright piece, however, was “But what would I know about life? I’m just a fish.”

Please, don’t do this to your reader.

6. Just as a story that’s too easy on a character can be too subtle to be engaging, a story that’s too hard on a character can fall flat.

I loved Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. I admired the novel’s generous and expansive view of friendship and sexuality. I loved the long-view it provided readers on complicated homosocial relationships, romantic love, familial love, and aging. But ultimately, the character the novel spends the most time with—Jude—is the least interesting to me because his suffering is so great and so constant that he ultimately has very little agency. (It’s worth noting that this seems entirely intentional, that part of the novel’s project is to look closely at a character who has been deeply harmed.)

Still, characters without agency can be lifeless on the page because they seem fated only to suffer and, therefore, we remain—for the duration of the text—unsurprised at their continual suffering.

7. Speaking of suffering, avoid using suffering, abused, or killed animals as objective correlatives.

A great objective correlative in fiction is worth its weight in gold. There’s tremendous pleasure in realizing that some physical presence in a story is working perfectly in parallel with a story’s thematic concerns. But harmed or neglected animals are such easy objective correlatives that, at least to me, they no longer surprise. I realize the irony of this advice given my own reaction to the death of Littlefoot’s mother (but, hey, I was seven). Adult readers and viewers are primed to read suffering, dying, or abused animals in particular ways. It’s why parents sense that Yeller’s gonna get it from the early moments of the book (and subsequent movie) even as their unsuspecting children delight in watching Yeller grow from rambunctious pup to protective pooch until the movie’s awful climax.

That parental intuition comes from having seen or read similar stories. We are primed, in other words, to expect certain actions in stories that present us with animals. For instance, if a character harms a domestic pet, we’re going to read that character as damaged or cruel. If an animal dies of neglect, we might easily see a causal relationship to the narrator’s poverty and to the story’s broader interest in economic decline. If the family dog escapes and is hit by a car and your character hasn’t worriedly gone looking for her, then we tend to see that character’s inaction in parallel to his generally dangerous lack of concern for others.

In other words, find better and less obvious objective correlatives than dead, suffering, or abused animals if you can.

8. Make your prose beautiful.

Yes, this is wholly subjective. It’s also the most wishy-washy piece of advice on this list, but hear me out. Just as my teenage self was never able to convince my brothers that the 1990s gothic metal band Type-O-Negative sucks, we’ll probably not ever agree on the exact nature of beauty. We may not even be able to articulate why we find something beautiful.

But you probably know what you find beautiful, and that’s all you need to start revising a draft. If you believe that your prose is going to be worth someone else’s time, make it worth your time by putting pressure on it and polishing it until, even if only in your eyes, it shines. Write prose to your own standards of beauty. Edit to your own standards of beauty as well.

It will probably not be enough; readers, agents, and editors will have their own ideas about how you should revise your work prior to publication. But you can’t get to that stage until you’ve first met your own standards.

9. If you’re working with a character whose attitudes, actions, beliefs, decisions, morals, or politics are suspect, alienating, distancing, or noxious, treating them with some modicum of empathy will make them palatable to readers.

This advice is a version of something Kaitlyn Greenidge says her New York Times piece “Who Gets to Write What?” Writing of a difficult and racist character in her excellent debut novel, We Love You Charlie Freeman, Greenidge writes: “As much as this character had begun as an indictment of all the hypocrisies of my childhood, she was not going to come out on the page that way, not without a lot of work. I was struck by an awful realization. I would have to love this monster into existence.”

Some of fiction’s most memorable characters are not entirely lovable. Though they’re entirely different people, Fuckhead from Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, Lelah from Angela Flournoy’s The Turner House, and Anders from Ted Thompson’s The Land of Steady Habits spring to mind. These people are interesting and engaging to readers because their authors have taken the time and care to provide readers with elements of their lives and personalities that we’ll find sympathetic. In thought and deed, these are nuanced, complicated people. They’re sometimes difficult to understand. Sometimes they’re funny. In some ways, they’re very much unlike the rest of us. But in recognizing how like us they are, in seeing how our concerns overlap with theirs, these characters become more memorable and easier to care for.

This is how we come to enjoy spending time with figures like Johnson’s violent, misogynistic, drug-addled Fuckhead (who seems, against all odds, like he truly and sincerely wants to be better person). Who can’t relate to wanting to be better? We enjoy the company of Flournoy’s Lelah because most of us understand something about what it feels like to be overwhelmed, overlooked, and a little lost. Thompson’s Anders is worth spending time with in spite of his shitty behavior because each of us desires, in some measure, what he does: to be forgiven the harm he’s caused. Johnson’s Fuckhead is an awful person; Thompson’s Anders makes fatal mistakes; and Lelah is merely a bit of a mess (of these three, she’s the most lovable by far), but none of these characters is all love and light. Still, we’ll spend time with them on the page because they are human—flawed humans, to be sure, but humans nonetheless. Mere empathy may not be enough to allow you to ably and reasonably inhabit the voice of someone entirely unlike yourself (more on this below), but it’s the lynchpin, I think, of our readerly ability to spend time with jerks and thieves, idiots and assholes, liars and incompetents, people who are (I hope) quite unlike ourselves.

Thankfully, purely evil people are uncommon in life and should probably be uncommon in our fiction or, at least, reserved for deep genre work like comic books and hard sci-fi and fantasy where they’ll find natural opposition in larger-than-life protagonist-heroes and anti-heroes.

As an addendum to this point: if the controlling motivation of a piece seems bigoted, misogynistic, cruel, or inexplicably violent, I’m going to stop reading the story. As readers, you probably know what it feels like to sense an agenda behind a writer’s prose. In editorial writing, you should be able to recognize the writer’s agenda. When it comes to fiction, I’m looking to be challenged, engaged, entertained, and moved. If I’m too distracted by egregious and inexplicable prejudice, misogyny, racism, or violence, then I’m prevented from participating fully in the world created by the writer. In fact, I may actively resist that participation. I can feel disgusted by a character and still want to read, but I shouldn’t be disgusted by the author or by what I sense behind the writer’s prose.

This is not moral prudishness. Work that is, at times, sexual (James Baldwin, Mary Gaitskill, James Salter) or violent (Cormac McCarthy, Toni Morrison) is often excellent and moving, but in each of these cases, the sex and violence is never wanton. Stories may use violence, hatred, and vulgarity in their service, but violence, hatred, and vulgarity divorced from purpose is capricious. Shock value, lazy humor, or the mere hydraulics of sex divorced from context seem pointless to me.

10. Err on the side of kindness rather than caricature when creating characters, and be thoughtful with dialectic speech.

What we’re doing in fiction is not at all what we’d want to accomplish in, say, investigative journalism or documentary filmmaking. In those modes, the goal is, most often, to record and faithfully report information.

By contrast, fiction asks that we exaggerate some elements of reality while downplaying others in order to maintain the artifice of a dream (I’m paraphrasing John Gardner here). If the reader is to inhabit the dream we’ve built, it’s incumbent upon us to direct the reader’s attention away from the artifice of the prose itself. (A major exception here would be experimental prose, work that draws attention to its own construction and syntax for effect.)

The use of dialect in fiction is complicated for a number of reasons, the most minor of which is that it may cause your reader to pause and to work too hard to glean your meaning. In other words, dialect that’s difficult to understand can easily shatter the illusion of the dream.

Much worse—and much more serious—is this: heavy-handed dialectic writing is used to lampoon and demean. Dialectic dialogue is the linguistic currency of minstrel shows and racist writing. All too often, dialectic speech appears in order to make a point to readers about the absurdity, stupidity, ignorance, inferiority, or frightful nature of characters who aren’t white, western, or wealthy. The racist and classist use of dialect in fiction aims to reinforce stereotypes rather than to provide context or character information.

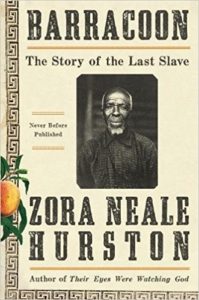

Compare the racist use of dialect to Zora Neal Hurston‘s Their Eyes Were Watching God and to her recently published Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” a history based on Hurston’s interviews with Kossola (the name given him/imposed upon him in the Americas: Cudjo Lewis), one of the last African-born, illegally sold slaves in the United States. In the book, Hurston preserves his speech patterns and vocabulary, which was one reason publishers provided for not publishing the book when Hurston first presented it to them; they’d wanted her to flatten the language by removing the dialectic transcription of her interviews. Where racist dialect aims to scold, diminish, and lampoon, Hurston’s approach works to depict—as accurately as she can—the unique speech patterns of a man whose language, culture, independence, and humanity had been stripped from him. Her replication of Kossola’s speech preserves his story and his use of language as he related it to her. Hurston approaches her subject with concern and care; a reader of Barracoon could never come to the conclusion that Hurston had set out to shame her subject or to make a caricature of him for the sake of white readers. If the same cannot be said of your approach, then ask yourself sincerely whether your interest in writing in dialect or from a perspective other than your own is born of mere curiosity or whether it’s born of concern and care.

The differences between being motivated by empathy and being motivated by love are vast enough to demand their own essay. Suffice it to say, my thoughts here on the limitations of empathy are formed, in a significant way, by this conversation in Sublevel magazine between the poets Rickey Laurentiis and Solmaz Sharif. Empathy—the imaginative capacity to be sensitive to another’s experience and even to experience thoughts and feelings vicariously—may not be enough when it comes to creating round characters. Something more is demanded of artists than merely the exercise of our imaginations. Empathy requires some effort, sure, but love—complicated, fraught, enrapturing, difficult, bizarre love—requires tremendous work. Think of how hard and how necessary it is to love through hardship and pain and how critical it is to be loved and to be able to love in return. Without empathy (not receiving it and not being able to engage in it), my life would be unimaginably diminished, but without love, my life would be over.

Incidentally, as I was editing this piece, I saw a tweet from Sharif that may be the best anchor in the choppy seas of this ongoing conversation: if you’ve never grieved in that voice, writes Sharif, don’t write in that voice.

Racist writing has a long history of being excused by arguments about historical and cultural context (e.g. “It was the way things were at the time” and “It’s how people really spoke”); curiosity, spectatorship, uninformed “admiration” (e.g. “I’m interested in this culture, so I will express this interest by writing about it”); and lazy poetic license (e.g. “Well, I’ve never actually met a Native person and I don’t know anything about any Native tribes or their traditions or cultures, but fiction writers should have access to everything right? It’s art!”). These attitudes lead to the very grossest cultural appropriators like Tim Barris and to apologists like Lionel Shriver.

If I’ve got three pieces of additional advice on this front, the first is this: don’t be Barris, and don’t be Lionel Shriver. Don’t loudly proclaim your right and ability to write from any perspective you choose and then pat yourself on the back for making said proclamation. This does not make Shriver a brave iconoclast or a righteous defender of artistic freedom. Frankly, it reveals her to be a jackass.

The second bit of advice on this front is to read broadly. Read writers who are not from your same cultural, national, or religious background. Read their fiction, their poems, their essays, and read their own reflections on issues of representation. Engage with writers and artists who are unlike yourself. And if, like me, you’re white: remember that you may not be the intended or best audience for all work; that not all work should cater to your experience; that other writers shouldn’t be expected to educate you (we have libraries and independent bookstores and the internet, so educating yourself is on you); and that writing can transport and transform us. Getting back to where this essay began for a moment: there is abundant pleasure to be found in those transportations and transformations. Why else are we reading? To see ourselves simply and easily reflected back at ourselves all the time? If you want “relatability,” buy a mirror and stare into it, but remember: Narcissus died alone on a riverbank because he found himself more interesting and more lovely than he found the world and the people around him.

Three relatively recent pieces of writing that have come to shape my own thinking about depiction and the way racist attitudes are manifested and maintained in the culture come from the aforementioned Kaitlyn Greenidge, as well as Elif Batuman and Jenny Zhang.

In “Reading Racist Literature,” Batuman looks at nineteenth-century work that explicitly demeans Turkish people (and points to the power of literary transmogrification), while in “Who Gets to Write What?” Greenidge examines the line between depiction and caricature. In “They Pretend to Be Us While Pretending We Don’t Exist,” Zhang cuts right to the chase, noting “White people have always slipped in and out of the experiences of people of color and been praised extravagantly for it,” something Greenidge also points to when she writes that, for many white writers, there’s “[…] the wish not so much to be able to write a character of another race, but to do so without criticism.” To be clear: Lionel Shriver can write from whatever perspective she chooses; what she should not do is expect that she won’t be criticized for it.

In each case, Batuman, Greenidge, and Zhang grapple with the long history of marginalizing and ridiculing people of color in English-language literature, which brings me to my third piece of advice on this front, which is based in part on their observations: given the long history of racist notions and racist depictions in fiction, don’t write work that continues or supports that racist legacy. Write work that subverts it, that upends it, that refuses to rely on lazy and racist shorthand. Put another way: recognize that racism exists, and work against it in your art. If this seems too big of a challenge or too high of a bar, you shouldn’t be writing.

—

Once, when my brother-in-law was studying astrophysics in college, I asked him how fast the Earth was orbiting the sun. His answer was thirty kilometers per second. Perhaps sensing that I had no ability to quickly convert kilometers to miles and seconds to hours, he said,”That’s about seventy thousand miles per hour.” I was stunned. I grabbed the edge of the table as if it might better anchor me to the planet.

We are rocketing through the solar system at incredible speed, just as the solar system is speeding through the galaxy, and the galaxy is whipping through the Local Group—you get the picture. My point here is this: our time is short, so write as best you can as often as you can. Write as beautifully as you can, then make it better. Write until you have to give it up, either because you know it’s done or because you don’t know what else to do with it. Then send it to a friend or send it to a magazine. Then wait and, while you wait, write something else. If you’ve gotten this far (in writing and in reading this essay), you already know it’s worth doing.

Nate Brown is the managing editor of American Short Fiction. Currently, he teaches writing at Stevenson University, the George Washington University, and Georgetown University. He lives in Baltimore.