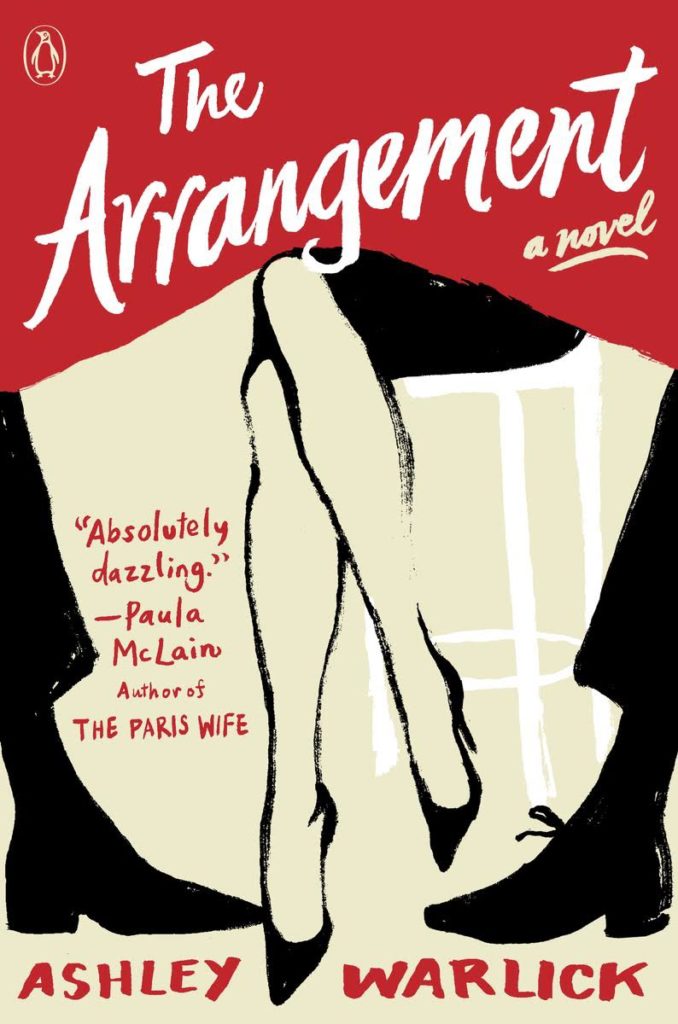

Ashley Warlick spent ten years on her latest novel, The Arrangement, a fictional retelling of the life and loves of famed food writer MFK Fisher. With lush, clean prose and pitch-perfect dialogue, Warlick lays bare the many appetites of a woman and writer ahead of her time. The novel spans the early years of Fisher’s career, a period marked by profound hunger as well as conflicting desires—for food, for recognition, for her husband Al and, later, for Al’s best friend, Tim. The book came out in paperback this winter; Ashley was gracious enough to chat with us about art and food and the delicate dance of re-imaging a personal history.

Ashley Warlick spent ten years on her latest novel, The Arrangement, a fictional retelling of the life and loves of famed food writer MFK Fisher. With lush, clean prose and pitch-perfect dialogue, Warlick lays bare the many appetites of a woman and writer ahead of her time. The novel spans the early years of Fisher’s career, a period marked by profound hunger as well as conflicting desires—for food, for recognition, for her husband Al and, later, for Al’s best friend, Tim. The book came out in paperback this winter; Ashley was gracious enough to chat with us about art and food and the delicate dance of re-imaging a personal history.

—

Rachel Howell: Why MFK Fisher? What initially drew you to her?

Ashley Warlick: Confidence is so attractive. As a writer, MFK Fisher was direct, un-shy, brilliant in her use of language, brave about her opinions, and the relevance of her subject, at a time when most women were writing cookbooks and housekeeping manuals. I read How To Cook A Wolf in college, long before I came to fully understand the value of these attributes for myself. And before I understood the value of my own kitchen, my own table.

RH: Did you have any inkling back then that you would someday write a book about her life?

AW: It was years and years later that I first thought to write about her. I’d just wrapped up the publication of my third novel, and my son was a toddler, and I was tired. I wanted to sink into somebody else. I came across Joan Reardon’s biography, Poet of the Appetites. Fisher’s whole long life was fascinating, full of lovers and kitchens, spanning continents and wars, and arching over all this was a strong sense of family, and place, and the importance of what’s shared over a meal.

I recognized something in her. Which is the relationship all writers have with their characters; I don’t think that’s saying anything new. These fictional people do and say and are so much more dramatic than we are, but at the core, there’s a reflection we recognize of ourselves. In Fisher, for me, it was the tremendous balance of tensions in her life that resonated immediately.

RH: MFK wrote often about herself, which is to say her life wasn’t exactly unexamined—what made you want to examine it further, and how did you come to choose this period in particular?

AW: Of course, her life was her subject. And she was a letter-writer and a journal-keeper. At first, it seemed like there was so much to consider, and to work with. But I kept returning to this particular moment in the biography, the beginning of her relationship with Tim Parrish, the beginning of the love triangle that marked the beginning of her career. It was such a nexus point and set a decade’s worth of emotionally impossible arrangements into motion. Narratively, it pulsed.

And for as much as Fisher wrote about this time in her life, returned to it, touchstone-like, she was never very honest about the context. I think that’s the case for a lot of us when we write about ourselves and a natural instinct in storytelling—it’s our job to distill, to streamline and make clear.

And a biography can clarify what happened, but not how it was imagined, survived, lived with later. This story seemed very much the job for a novel.

RH: All writers take pains to get their characters “just right,” but there must be added pressure when a character is based on an actual person, not to mention one who was a writer herself. How did you deal with this extra weight during the writing process?

AW: I didn’t want to fail her, or imitate her, and finding a way to capture her was my biggest initial challenge. Most of the research I did for this book was reading, and most of that reading was in Fisher’s own voice. Pretty soon, I came to see the differences between how she wrote to herself versus to her intimates or for publication—shifts of tone, yes, but more importantly to me, of subject. Quite literally, her perspective was different as a writer than it was as a daughter, a wife, a lover, or an observer of her own life. She noticed, and cared about, different things. That realization opened her character for me.

RH: You strike a wonderful balance. The book very much has its own voice, but it also manages to capture a certain unsentimental sensuality that MFK brought to her work. I’m thinking of the food descriptions in particular. Were those the hardest for you to write?

AW: I’m a self-taught home cook, the marginally obsessive kind Fisher would have probably been a little mystified by, later in life. I read cookbooks like novels. Thomas Keller has this recipe for roasting chicken I think might be the most intimate thing I’ve read in my life. And I fell in love with cooking because I was good at it, and loving it makes me better at it, but also as a direct result of realizing myself as a novelist. I needed a satisfying creative outlet that didn’t take so long to carry out. Consequently, I think a great deal about food. Writing about it comes very naturally to me. I’ve always loved the way a description of a meal on the page is instantly fully dimensional, engages a scene on every sensory level. Food is powerful in the moment, and in the memory too—which is obviously something Fisher was very familiar with. But her cool hand is very different than mine. In general, she’s way cooler than I am.

RH: At one point Mary Frances muses, “It wasn’t love that made her want Tim, that turned her car around on the dark highway and brought her back to this moment, it wasn’t love, but rather an appetite’s demand: direct, imperative, true as love perhaps, but far more dangerous.” The book makes it clear they both loved their respective spouses a great deal, and yet their pull towards one another, both sexually and intellectually, seems driven by forces out of their control, or at the very least by ones that are primal and uniquely difficult to resist. How have readers responded to Mary Frances and Tim’s affair? Do you find readers are quicker to sympathize with and/or vilify characters based on real people versus those who are purely fictional?

AW: To be honest, I try very hard to stay off the Amazon page, where folks feel free to say any damn thing they want, and when I’ve talked about this book to book clubs or in bookstores, people are loath to vilify. I mean, I’m sitting right there, and these are generally nice ladies, and they assume I’ve got all kinds of dogs in this race. . . But there’s not a great deal of love expressed for her either in these conversations. There’s awe. There’s curiosity, fascination. And there’s sympathy born out of considering her time and place in the world, how clearly outsized she was for it.

I’ve been thinking about an aspect of Tim and Mary Frances’s relationship lately that raises all kinds of feelings for me, how their physical connection naturally followed their creative one. I mean, they are all tangled up in this, aren’t they? And Tim had means and connections that opened professional doors for Mary Frances. Did he honestly support her work? Yes. Did he hold power over that work? He did. In bright light, that’s uncomfortable.

I remember wondering early on, in that first scene, what would they talk about over dinner. It was the moment of Tim’s praise that opened the rest of the night for me. He says these powerful things he knows she wants to hear about her talent. It’s currency between them. And I believe, even as blithely as he went home, dropping his clothes in the hallway for his maid or his wife to pick up, whoever got there first— I believe he knew the match he was striking with Mary Frances.

But she surprised him and set the whole house on fire, so to speak. And she pushed that relationship forward for the better part of a year using her work, the intellectual, creative spark between them. Her willingness to take her wants into her own hands liberates their story somewhat for me, brings their conversation to a more interesting place than it began. I do wonder if by making Tim more sympathetic in this regard, Mary Frances becomes less so. All three of them are devastatingly human.

RH: Devastatingly. Which is why the book resonates so powerfully. But talk for a minute about accessing that intimacy. From what I’ve heard, and from the one book of hers I’ve read, when it came to matters of the heart, MFK was rather opaque. Mostly she stuck to food, and France, and family, though as her obituary in the New York Times made clear, she equated writing about food with writing about “love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it.” How much of her personal life, the intimacies and private conversations that the book displays so vividly, were you able to mine directly (or indirectly) from her words, and how much was purely the result of your imagination?

AW: She was not given to sentiment in her writing life, no. But food was a powerful metaphor for her; she saw everything important in it—comfort, desire, memory, need and satisfaction. So much of what I learned about her emotional life, I learned from her essays laid against the historical timeline I gathered from her biography. The friction between her persona on the page and what was afoot while she was writing the page offered tremendous insight into what she must have been feeling. Or dealing with feeling. In short, her essays weren’t very honest about her private life. The challenge, and pleasure, of writing this book came from trying to imagine how she did what she did, what she was thinking, how to show why.

RH: When I first read the book last year, I wrote you afterwards to tell you how much I loved it. In your response you shared a crazy story about MFK’s daughter, Kennedy Golden, showing up at a reading you were doing in California. Can you summarize that encounter for those reading this, because it’s just so wild. I’ll preface it by saying that you and Viking decided not to share the manuscript with anyone in MFK’s family prior to publication, so this was a complete shock.

AW: So I was giving a reading at a bookstore in Berkeley, Mrs. Dalloway’s, and waiting in the back office when the manager comes back and says, “Kennedy Golden is in the audience. Would you like to meet her now or afterwards?”

AW: So I was giving a reading at a bookstore in Berkeley, Mrs. Dalloway’s, and waiting in the back office when the manager comes back and says, “Kennedy Golden is in the audience. Would you like to meet her now or afterwards?”

The only answer to that question is now. Kennedy was very very generous. She looks so much like her mother, particularly through the eyes; I would have recognized her immediately. She said they’d all heard about the novel and were just beside themselves about it, particularly her sister Anna, who is very private. And they’d gotten their hands on a copy and read it quite prepared to tear it apart, but found they couldn’t. She said she felt I’d done a good job with her mother, which was such a compliment to me at the time. And then she said if her aunt Norah had been alive, she would have been furious. She was very protective of her sister. And we went down that path for a little bit, her real people reacting to my imagined ones pretty much like how I’d imagined they would. Understand, this office was all of 4 square feet. And I was sweating.

RH: So what were the reasons for not showing the family the manuscript ahead of time? Were they aware of the book’s existence at all before it came out?

AW: My reasons were all very simple. I wanted my ideas about MFK Fisher to come from Fisher herself, following the circuitry I was familiar with, from a writer’s life to her work and back. Otherwise, once I started interviewing people, when would it be okay to stop?

It’s funny. You learn very early on in fiction workshops, the dumbest thing you can say in defense of your work is, “But it really happened!” It doesn’t matter if it really happened. What matters is what I can make you believe happened, what I can make you understand after it’s happened. This period in Fisher’s life is such a clear example of the power of imagination.

The family was very aware of the novel. Robert Lescher, Fisher’s agent, had been aware of the novel in progress, and when he died, Kennedy became her mother’s literary executor. The Arrangement was published in February 2016. The previous fall, Viking became aware that Fisher’s novel, The Theoretical Foot, would also be published on the same day in February 2016. This novel was one of many Fisher wrote over the course of her life but never published. She was not a gifted novelist. It’s relevant to The Arrangement, however, written in the late 1930s, set in Switzerland in a house like Le Paquis, filled with very autobiographical characters.

RH: Tell me about the poem by Richard Siken, “Scheherazade” that you chose for the epigraph. I must say I’m a little bit obsessed with it. It’s breathtaking on its own, but also sets the perfect tone for the book. Did you have it in mind as you were writing, or did you discover it afterwards?

AW: Siken’s collection Crush is exactly how I like my poetry: obsessive, lush, fervent to within a breath of sanity. I discovered that poem somewhere early on in the novel’s progress, by way of my friend Mamie Morgan, poetry instructor at South Carolina Governor’s School of the Arts and Humanities. I was teaching fiction there at the time, and we shared a desk. I would leave stories, she would leave poems. Instantly, it clicked: the lake, the dancing, the desperation of the kind of love it describes.

RH: You worked on this book for ten years. Can you talk a little about that process? I’m interested in hearing how you stayed devoted the same project for so long. Did you ever come close to abandoning ship? Were there times you found yourself growing tired of the characters and itching to move on to something else? How did you maintain course for so long?

AW: Ten years. This is going to sound impossible, but the only time it occurred to me to quit was year two. Long story short, Fisher’s last agent, Robert Lescher, was her literary executor and controlled access to her collected papers at the Radcliffe Library. I wanted to see them. They’re all cataloged online—I knew which boxes I wanted to see. I wrote him a letter, but he’d already granted exclusive access to Anne Zimmerman, who was working on a biography that his agency ultimately represented. It’s an interesting biography: An Extravagant Heart. It begins with Al and MFK’s marriage in 1929 and follows her life through about 1945, so much of the same territory as The Arrangement. I don’t entirely agree with some of the conclusions Anne draws about Tim and Mary Frances, which I love to be able to say. I love the idea that even biography can be subjective.

Anyway, Lescher declined my request. And for a couple months, in spite of all the mapping and reading and thinking I’d put into this project, I felt like I’d lost important ground. I worked on another novel project. I stared at the wall a lot. And finally, honestly, I just said fuck it. I wanted to write this book. I felt compelled to write it, and I was going to write it until I was happy with it. And so these ten years were kind of born out of a sense of freedom.

I finished a good draft in 2011. And my drafts are careful ones, I edit as I go, build today’s work by polishing yesterday’s, because that way a novel is made in small and manageable steps. Nothing happens too fast. That draft had pacing issues, was about 100 pages too long, but also lacked a sense of Fisher’s significance, what she would go on to mean in the world of food and letters. It took me a couple of years of thinking to figure out how I wanted to solve that problem.

I always saw it as a luxury, to be able to take all the time I needed to take to get the book I wanted to get. This is not to say there was not a period of abject slog, but that’s a familiar part of novel writing for me. Once I have a beginning, middle, and end, editing is where all the connective tissue gets made, the synapses fire and light up things you must have done subconsciously, or the book must have done for itself. All those weird, wild, magical feelings keep pushing you forward.

RH: What advice would you give other writers who find themselves struggling to stick with a project over the long haul? Do you have any writing rituals? Any words of wisdom that have been helpful to you in moments of struggle or self-doubt?

AW: In terms of ritual, yes. I believe, when you are drafting a novel, you must spend time with it every day. I believe in word counts or page goals, and when you meet those goals, I believe you should step away from your desk happily and make lasagna Bolognese, watch movies, fold laundry, meet girlfriends for wine—because if you don’t, you will never have any sense of accomplishment. When life gets frantic, set time goals. An hour at the desk, uninterrupted. But allow yourself the relief of accomplishment.

(Editing is different: mad, passionate, up-all-nightness, and great, if unsustainable, and shouldn’t be sustainable because you are holding a whole novel in your head and there’s not room for anything else, like the baby’s antibiotic schedule or the fact the dog hasn’t been out. That’s not a life. As artists, we must also make lives that can sustain art.)

In terms of wisdom, I have the good fortune to have been raised in a family where instinct and intuition have always been more valued than book smarts. There’s a lot of confidence to be found in that thinking. Doubt becomes an occasion to consider choices, other perspectives, which is very much our job.

RH: Who are you reading right now? Which authors have been your biggest influences, and how has that list evolved over the years?

AW: I just finished Lincoln in the Bardo and can’t shut up about it. Or about what a lovely voice in these times I think George Saunders is. I saw your transcript of his talk at Parnassus online the other day and copied it for myself, sent it to three friends. Because how true: we need to double down on art right now. It makes us bigger, more empathetic people.

Here’s where being a buyer for a bookstore gets thick, however. I’m also reading South and West, Joan Didion’s recently published notebooks about an essay she never ended up writing. She’s drawing a comparison she sensed but couldn’t ultimately articulate between the frontier attitudes of California and the deep rural South, a kind of mutually exclusive spirit of independence. I’m also reading Susan Perabo’s new novel, The Fall of Lisa Bellow, which is about a stunning kind of tragedy where two eighth-grade girls are shoved to the floor during a stickup, and one gets taken hostage and the other doesn’t. How we survive those kinds of acts of God, as people, as families. It reminds me a little of The Lovely Bones. I’m also reading the first several chapters of about 25 books that will be out this summer.

RH: I picked up a copy of Best Food Writing 2015 last year and was completely absorbed by many of the essays in it. Where do you turn for good food writing, and who are your favorites writing about food today?

AW: Give me a good chef-driven cookbook any day. Anthony Bourdain’s Appetites is opinionated and brash and a little dirty. Vivian Howard’s Deep Roots has such practical elegance. Katie Button’s Curate, because I have such a soft spot for Spanish food and that restaurant. John Currence’s Big Bad Breakfast is fantastic, and he’s one of my favorite cookbook writers. Pickles, Pigs and Whiskey has playlists with the recipes, for godsakes. I still read Bon Appetit and Saveur religiously, troll the NYT Food section, and several online apps. I like to plan imaginary dinner parties while I’m waiting for the dentist, that kind of thing.

But for food writing in its pure, unadorned-with-recipes form, I have some standards I return to again and again: Laurie Colwin’s collected columns from the New York Times, Home Cooking. Darra Goldstein’s magazine Gastronomica. Mark Kurlansky’s history of the planet through a single element, the most misunderstood element in cooking today, I think, and the easiest way for a dish to fail, Salt.

RH: Food seems to be having a cultural moment, and not just food but cooking and an interest in all things culinary—from reality competitions to more nuanced shows like Chef’s Table and Cooked, as well as the prevalence of food blogs and farmers markets. One New York Magazine headline posited not that long ago, When Did Young People Start Spending 25% of Their Paycheck on Pickled Lambs Tongues? If MFK were alive today, what do you think she would make of all this food focus, and where would you imagine her fitting in as a writer and contributor to the overall narrative? Could you see her embracing a kind of celebrity role, or would she have likely avoided the spotlight?

AW: She saw the edges of this foodie culture, that’s for sure, for better and for worse. Think about where food and wine was in California in the 1980s—I mean, that’s where California cuisine comes from, in the fussiest, nouvellest interpretation, and she thought it was flat ridiculousness. There’s a wonderful piece she wrote for Vogue about how American women are afraid to take pleasure in tasting anything. And knowing how Fisher linked taste to appetite to desire, you can pretty much follow her thread there.

So, here’s where her legacy gets interesting for me. She had a kind of celebrity role in her day. People made pilgrimages to her house, bearing cheeses and wines and tomatoes from their gardens, and invited themselves for lunch. Anne Lamott, Alice Waters, she was lifelong friends with the Childs, with James Beard. Bill Moyers interviewed her late in her life, penciled eyebrows and that high tremolo of a voice, about the nature of love and loss and aging. I believe she welcomed the spotlight. I don’t understand why she doesn’t have more of a spotlight on her now.

Because even way back at the beginning of her career, MFK Fisher was talking about all the things the sustainable food movement seems to have just discovered: food grown locally and in season tastes better; animals deserve respect, both on the plate and in the field; that honest food, treated simply, is the finest food in the world. But she was also concerned with all this magnificent stuff about how we sustain ourselves.

When I was throwing a party at the bookstore for the paperback of The Arrangement, I got it in my head that I was going to make Fisher’s recipe for gingersnaps. It’s a very Fisher sort of recipe, and one I pulled from her letters, actually a response to someone who’d asked for the recipe. She begins the letter with an apology for taking so long, but the holidays had been so hectic, and here the letter writer was probably hoping to make these gingersnaps for Christmas. Really, her recipe was just the recipe from The Joy of Cooking, only she tripled the ginger and made them very small, like the size of quarters. They’re spicy, and great with wine, and perfect party food.

Through a comedy of errors involving the same pound of butter being put in and out of my fridge at least three times, I ended up making the gingersnaps at 5 a.m. on the morning before the party, because I also had to work at the store all day. I get to the dry ingredients and realize I don’t have enough flour. Into the car, out of the neighborhood, and left, there’s the closest grocery. Right, there’s the grocery I know is open 24 hours. I pick close, which doesn’t open until 6 a.m. Sitting in the parking lot, waiting for the store to open, it occurs to me: what would Fisher do?

I wrote Kennedy right then, asking, even though I could guess the answer. She would have just made do with what she had. As her daughter said a couple hours later, she was a very resourceful woman.

RH: What are your thoughts on writing and being a writer in the midst of the current political climate? I think it’s something most writers, and artists in general, are grappling with right now. I know I am. Would you say writers have an even greater obligation to put truth and beauty into the world right now, or does that kind of thinking add unnecessary pressure to a discipline that is already inherently difficult? How do you personally keep going in the face of so much noise and division and negativity and just general what-the-fuckness?

AW: I am a very liberal, open-minded novelist who has made a home in South Carolina for the past 20 years. I have long been politically at odds with my surroundings. Which is not to say these are comfortable times for me. But simply, that I am in a familiar situation. I mentioned George Saunders’s comments earlier about what the world needs now, and I believe that’s true. But by double down, I think that means everywhere, not just at our own desks. Buy art. Teach your kids about art. Make art. Make cookies. Make things. Another hero of mine, Amy Krouse Rosenthal, just passed away a few days ago. She wrote the book Little Pea, which my kids and their dad and I can all recite from memory. That was one of her mantras: making things makes things better.

RH: The writer Richard Bausch has said, “Writing is always an act of optimism, because there is the faith that some intelligent, civilized other might be around to read it.” Lauren Groff went so far as to thank “the readers of all books” in her acknowledgments of Fates and Furies, and said in an interview that every time she does an event, there’s a part of her that wants to hug everyone in the room. You opened a bookstore not that long ago, M. Judson Books, in your hometown of Greenville, SC, so you must have some faith in the existence of those intelligent others, yes? Do you share that sense of gratitude? Do you want to just hug every person who reads one of your books or comes into your store?

AW: There are days it feels like evangelism. When we opened the store, Pat Conroy came to a special dinner we hosted to thank some of our biggest supporters. This was the fall before he passed away. He was a terribly generous force in my life, and in the lives of so many writers. He started Story River Press at USC and personally shepherded so many new Southern voices into the world. Talk about what the world needs now. Anyway, we’ve got this long table laid down the middle of the bookstore, and the wine is flowing, and the food is marvelous, and midway through dinner, Pat stands up to thank the people gathered there for supporting us. He says, “Bookstores, for me, are like churches. They do more for the spirit.”

Amen.

Ashley Warlick is the author of four novels; the most recent, The Arrangement, was published in February 2016. The recipient of an NEA Fellowship and the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship, she has published work in Oxford American, McSweeney’s, Redbook, and Garden and Gun, among others. She teaches fiction in the MFA program at Queens University in Charlotte, North Carolina. Warlick is also a partner at M. Judson, Booksellers and Storytellers in Greenville, SC, where she lives with her family.

Assistant Editor Rachel Howell received her BA from Kenyon College and her MFA in Creative Writing from the low-residency program at Queens University of Charlotte. After ten years in Austin, she recently returned to her hometown of Nashville, where she lives with her husband and two young children. Her short fiction has appeared in Atticus Review.