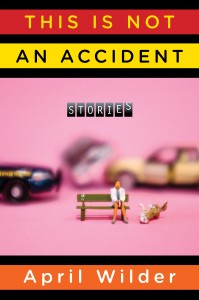

The stories in April Wilder’s debut collection, This is Not an Accident, inhabit, in her words, “the territory of the American absurd,” and each first page is like the edge of a cliff. A story might begin, say, in a defensive driving class or in a kitchen with the grandchildren, and then it careens off, suspending the reader in that place where falling feels like flying. Take “Creative Writer Instructor Evaluation Form,” which we were so lucky to publish as this month’s Web Exclusive; the way it subverts and surprises, the stakes growing ever more urgent, calling attention to the hysteria in hysterical. But what’s most striking in these stories is how her characters so earnestly navigate their alienation and longing through the peculiar and yet peculiarly familiar messes they find themselves in. April was kind enough to talk with us about the book, about writing a sentence that dares you to keep writing, and about disequilibrium and the idea of a story that makes you laugh so hard you have to write it.

JS: I think that readers and reviewers can do a disservice to short story collections, when they feel compelled to find some overarching theme, some ring to rule them all. For certain authors, it seems like it’s intentional, but I also like the rewards of a collection that asks its reader to take each story on its own, not in relation to or in service of some grand observation. After reading This is Not an Accident, I don’t want, for instance, to try to force-tether Odd and Laney, of the story “It’s a Long Dang Life,” to Jack and Ann and Monahan and Turtle, of “The Butcher Shop.” Do you think I’m full of shit? And more importantly, how did these stories come together to create a collection?

AW: I was working less with a theme than (if anything) a territory: the American absurd. Albert Camus defined absurdity as man’s feeling of alienation in the face of an “indifferent universe,” a state that causes a “divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting.” More recently, David Foster Wallace located absurdity in “the conflict between the subjective centrality of our own lives versus the awareness of its objective insignificance” which he called “the single great informing conflict of the American psyche.”

In this collection I wanted to look, then, at America’s particular lugubrious brand of absurdity. To ask what is it in our systems, and the life situations they create, that leave so many of us feeling estranged, alienated, self-alienated. Take the first story [“This is Not an Accident”]. I have been to that bar; it’s on the tip of Montana. I drove three hours with a friend to see it. It was a quiet night, a Monday, just me and my friend and three yawning regulars, and behind the bar, a woman in a monofin swimming around. A woman who was being paid to impersonate a fish—not even a fish, but a made-up species, while we watched her and drank intoxicants. You can’t sit there five minutes without wondering about that girl, what such a job would do to her worldview. I mean, they built the place, they are paying her actual money to do this, the job was in the Want Ads, etc.—there is evidence everywhere that this is not a joke. I’m not sure this bar could exist anywhere else on Earth; if it did, it would at least sit within a secure ironic context. For me, that’s one of the richest things about America, that we don’t all get each other’s jokes, and we’re not always sure whose jokes we do get, and who’s joking and who’s not joking one fucking bit. At any rate, I think you will see that the other stories in the collection deploy their characters into similarly (Americanly) alienating situations to observe both the processing and end product.

JS: About that absurdity–I think something you’ve done so well is to show these kinds of shining moments of clarity within it. Like in “This is Not an Accident,” when all these peculiar events and images are swirling around, and Kat says “You don’t need a locked door to sleep, you only need to have checked the lock.” Or that it takes a swallowed tooth, a rare steak, and a scene in a restaurant for a husband in “The Butcher Shop” to come to this conclusion about his ex-wife: “He has to start not telling her things.” There’s this kind of push and pull, after you’ve read the book, when you think about what you remember most from the stories: there’s the mermaid bar, the commune, the fake baby–these arresting images–and yet there’s these really quiet conclusions, like “It’s a long dang life.” That seems like a really important balance–to not get sucked into the absurdity vortex of a story so much that you lose what’s at the heart of it, like somebody just trying to make it in one piece to the next day.

AW: One thing you have to guard against, if you are going to populate an absurd landscape, is making the people, also, absurd. Otherwise you end up with a double negative effect—in a madhouse nobody’s mad. So if I’m going to strain your credibility on one level, then it seems to me good manners to hold something else constant. In this collection (in general) my constant is the thought processes of one or more characters. By constant, I mean trackable but not (necessarily) trustworthy. So while I will tell you directly what the characters are thinking—and you can trust that they are indeed thinking what I tell you, and (for the most part) you can even trust that what they are thinking is actually what they think they are thinking—I hope that their revelations and/or epiphanies sound a little off given all that you (the reader) know. The last line of the book is the only one I trust completely. (I guess that ‘s why the book had to end there). [Editor’s note: the last sentence is an entire paragraph, but it ends: “…and Billy behind watching, always farther behind, and Eckhart thinking that nothing hurt like trying to come alive.”]

JS: The notion of what a “novella” is seems to be somewhat murky (maybe akin to: is this a prose poem or a flash or a short story?). Calling “You’re That Guy” a novella separates it from the other stories, a little like what I mentioned before—“This is its own thing; let it be its own thing.” Was “You’re That Guy” always a novella? When you were writing it, were you thinking of it as a novella and not a short story? And if so, what do you see as the difference?

AW: I also am unsatisfied distinguishing between a short story (SS) and novella solely on length. I think readers have different formal expectations of novellas as well—certainly in terms of pacing, unity or “single effect,” dimensionality, the character net, etc. One thing versed SS readers won’t brook much of (importantly for the piece we are discussing here, YTG) is lard and/or ‘extra stuff’, and I knew in writing YTG that I needed more room than SS readers would allow me to risk going nowhere often (Eckhart lying on the couch looking at a grasshopper). I doubted, were YTG presented as a “short story,” that readers would’ve persisted beyond page 20 (“Ok WHAT do you want me to focus on, here, lady?). I’ve noticed over time that a lot of technical decisions are made in the service of getting permission from your reader to tell a certain story, or tell it a certain way, or to make a move. With YTG, I needed permission to meander and shoot out in odd directions. I needed to buy some time. By calling YTG a novella, I hoped/knew readers would allow me a wider berth, and YTG ended up long enough I could get away with calling it one. In short, where it says “novella” on the title page, read: BE PATIENT.

[As a side note: At one point, YTG was over two hundred pages, so originally it was a matter of adding the “la” to “novel”—slimming down—rather than beefing up a story)

JS: Can you talk about how you work to set up a reader’s expectations in the first sentences of a story? (I’m thinking of that great beginning to “We Were Champions”: “A few days after Stephanie called and told me Bob had shot himself in the foot then the gut, Sammy Sosa got caught corking his bat.”)

AW: To be honest, I’m usually more worried about my own expectations (than readers’) when I’m setting up a story. Normally what you see in my first sentences/scenes is me trying to seduce myself into telling the story. The sentence you quote from “We Were Champions” is a good example: imagine writing that sentence, reading it back to yourself, then daring yourself not to continue.

JS: How hard is figuring out where and how to end a story? You don’t seem to be afraid to let your characters come to a conclusion, even if its ephemeral. It’s so hard to do that and have it work. When you read a great ending to a story, it feels like a writer has tapped into a kind of elusive magic, when in reality, writing that great ending is the result of painstaking hard work.

AW: For me, the most useful image of a short story is that of a system that, responding to some circumstance/event/etc., is thrown into a state of disequilibrium (D) from which it must engineer a new state of equilibrium E2 (‘the center cannot hold’): E1 –> D –> E2 . In “Creative Writing Instructor Evaluation Form,” what is thrown into disequilibrium is the social contract between student and faculty, a disequilibrium manifests materially in the form itself, which begins falling apart until the bubbles are filled in*. If you buy the disequilibrium argument, then it should be true that I (the writer) should be able to find—if what I am writing is a proper short story—some relationship or character or whatever that was knocked off balance to set the story in motion, and then it’s a matter of looking for your new state of equilibrium. The couple times this has worked for me, I found that it was actually very difficult to keep writing beyond the point E2; every word feels irrelevant. More generally, if you really really can’t find a resting place, make sure you have a story to begin with and not just a description of someone somewhere doing something (or not doing something)—a “scenario rather than a story,” in workshop speak. A scenario has no logical end to find.

* You asked me how a story like CWIEF comes about. I was looking at a survey form one day and asked myself, I wonder how you’d work a plot into one of these? That got me laughing so hard I sat down and wrote the story on the spot, more or less in one sweep.

April Wilder is the author of This Is Not An Accident. Her short fiction has appeared in several literary journals, including Zoetrope, McSweeney’s, and Guernica Magazine. A former Fiction Fellow at the Institute for Creative Writing in Madison, Wisconsin, she lives with her daughter in Salt Lake City and California. Visit her online at: http://www.aprilwilder.com/

Jess Stoner is the Managing Editor of American Short Fiction and the writer of stories, essays, and poems that appear in The Morning News, The Rumpus, Caketrain, Necessary Fiction, and other handsome outlets. Her novel, I Have Blinded Myself Writing This, was published by Hobart‘s Short Flight/Long Drive Books.