We were immediately enchanted by our October web exclusive, Ihab Hassan’s “Three.” Sadly, Dr. Hassan passed away shortly after we accepted his work for publication. We would have loved the opportunity to speak with him about the pieces, but his colleague and friend, the author Liam Callanan, was kind enough to share some memories and insight. Suffice it to say, we would have loved to be the man’s dinner companions.

We were immediately enchanted by our October web exclusive, Ihab Hassan’s “Three.” Sadly, Dr. Hassan passed away shortly after we accepted his work for publication. We would have loved the opportunity to speak with him about the pieces, but his colleague and friend, the author Liam Callanan, was kind enough to share some memories and insight. Suffice it to say, we would have loved to be the man’s dinner companions.

Erin McReynolds: We were so sorry to hear of Dr. Hassan’s passing. How far back did you two go?

Liam Callanan: This is such a simple question, but the answer’s tricky. I would have said that we went back ages, but doing some digging in my email inbox, it looks like we only go back to 2008 or so. He came to a reading of mine, sat in the front row, told me afterward that I read far too fast—which I did, and do—and asked if my wife and I would join him and his wife for dinner. Those dinners continued once or twice a year, and were like none we’d ever been to before—nor will attend again, sadly. Usually it was just the four of us, and we’d tour the world several times over before the check arrived: what did I think of Harold Bloom’s latest pronouncement; where to stay in Paris and why the bartender at the Ritz was without peer; hiking with David Malouf in Australia and lifting weights with George Garrett on the roof of the American Academy in Rome. This makes it sound like he did all the talking, but that was the extraordinary thing—he didn’t, he really wanted to hear what you had to say, and I always really wanted to say something worthy of that intense interest. You couldn’t get away with cant (or can’t). We’d come home spent—but happily spent, exhausted like after a good workout, which is, I see now, what those meals were, the roof of the American Academy not being immediately available to us.

EM: Had you read any of his fiction before “Three”?

LC: I had read some; we didn’t exchange draft work, but every so often, when he would publish a piece, he would make sure I got a copy. They would always arrive without fanfare in my inbox or more frequently, my actual mailbox at the university. This work is shorter, more compact, more dense, but otherwise, very much of a piece with what else of his that I’d read recently.

EM: If you can speak to it, how would you characterize his approach to fiction, as both a writer and a critic? Who were his influences, or who had his approval?

LC: Ihab is gone, but I can very much feel him at my shoulder as I consider this question, and I think I can see him smiling and shaking his head, which I’ll take as blessing—or urging—to evade it as best I can. He really did read widely—wider than anyone else I know—and so the ranks of those who had his approval spanned decades and continents and was fairly dynamic. He kept up with literary journals, and even city magazines. I remember getting a nice note from him after I published an essay in Milwaukee Magazine. I thought, he reads that, too? He was a fan of his friends, of course, and often mentioned Malouf— indeed, Ihab and his wife loved Australia and felt very much at home there. I think in an alternate universe they would have lived there, but instead, Milwaukee was home base for all their peregrinations.

EM: There’s an inconclusive sort of kinetic energy to each piece’s ending, a sense of expansion beyond the character, as if to say you are both the point and not the point. I may be asking you to take a leap here, but does this suit any understanding you had of his sensibilities about fate, mystery, the universe?

LC: It’s hard to read these pieces, especially so soon after his death, in any other context than his death. And so as much as I don’t want to read them as a summing up, or an ars poetica—because I don’t know if (and doubt) that was his intent—there they are, touching on so much that was absolutely core to his being: leaving Egypt, traveling the world, Australia, eternity (cf. Stace), and, of course, minding the gap. I think—and here I wander out on a ledge—that gaps, the gap, fascinated him, and always had. We never talked about theory, and, odd as this may sound to those who only know him through the term, the five syllables of “postmodernism” never passed between us. Theory, postmodern or otherwise, was a country he’d left some time ago. He continued to read and discuss criticism with my colleagues, but his energy for the last decade at least was very much spent writing his own fiction.

That said, my sense is that his sense of the postmodern turn, what interested him most, was that gap between what was and now would be. It’s a really fraught space, and I think each piece in “Three” addresses that. So far as I know, he never returned to his native Egypt. But of course, in his fiction he was forever going back, quietly, thoughtfully, constantly.

A few years back, we were exchanging emails about a Louis Menand piece in the New Yorker about creative writing programs, were they a menace and so on. I’m a product of one, teach in one, so have my bias, which I shared. Ihab replied, “For me, the old moral is: if you’re a writer, go your way.”

And of course, that’s exactly what he did. Went and went and went.

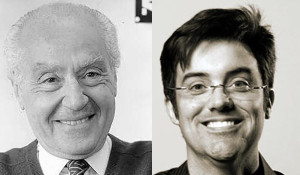

Ihab Hassan was born in Egypt in 1925 and immigrated to America in 1946. He earned a doctorate in literature at the University of Pennsylvania in 1953 and taught at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Wesleyan University. In 1970 he became a Vilas Research Professor of English and Comparative Literature at UWM, where he remained until his retirement in 1999. He wrote 15 books and more than 300 articles on literature and culture, and is widely credited with coining the current contemporary use of the term “postmodernism.” Dr. Hassan passed away from a heart attack on September 10, 2015.

Liam Callanan is an associate professor in and former chair of the department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Ihab Hassan’s academic home for almost thirty years. Liam’s most recent book is Listen & Other Stories.