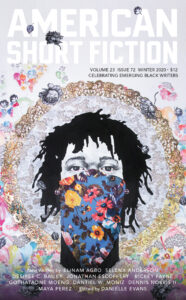

ASF is recognizing Black History Month by sharing, for the first time online, four stories from our Winter 2020 issue, which showcased emerging Black writers selected by guest editor and PEN American Robert W. Bingham Prize winner Danielle Evans. Here is author Maya Perez, reflecting on the experience of writing this story:

ASF is recognizing Black History Month by sharing, for the first time online, four stories from our Winter 2020 issue, which showcased emerging Black writers selected by guest editor and PEN American Robert W. Bingham Prize winner Danielle Evans. Here is author Maya Perez, reflecting on the experience of writing this story:

My initial idea for the story was two people with a shared history having a reunion and realizing that while they don’t know each other at all, they share an overwhelming loneliness that only the other can understand. Despite her massive high-school crush on Doug, Violet knew who he was no better than he’d known who she was, albeit in different ways.

Additionally, like Violet, I grew up in different cultures and sometimes felt like a stranger within my own country—within my own family even. I think everyone feels this way at some point, finding their circumstances so alien, they might as well be on another planet, that we are pioneers forging our way through the foreign lands of grief, feeling like an outsider, feeling like we have no idea what to do with our lives.

— Maya Perez

—

Violet stepped out of the noodle shop and remembered to check that they had included the chili sauce she’d requested. She was working the dinner shift at the oyster bar in a few hours and didn’t need to be spending money like this, but she was tired of the bar’s menu and even more tired of the leering kitchen staff.

“Go ahead,” she said to the man waiting outside by the door.

Yes, the chili sauce was in the bag. And the man was still standing there.

“Go ahead,” Violet repeated, shifting farther out of his way, but the man wasn’t waiting for her to move. He was waiting to talk to her.

“Can I help you?” Violet asked.

“I saw you through the window. I think we went to high school together.”

Violet looked at him more closely. He was leaner than he used to be, angular and sharp-edged. And his hair had darkened to sand with strands of silver throughout.

“Doug Foster,” she said.

He nodded.

The one year Violet had attended high school in Houston, she had loved Doug Foster so much it hurt to be near him—throat in a vise, clenched heart. Doug was two grades ahead of her at Forest Park, and she would seek out his face in the hallways and at the football games and keg parties she went to with her cousin Lucy. Violet was from Lusaka, and her impressions of America—of American teenage boys, in particular—had been formed by bootleg VHS tapes of Lucas and Sixteen Candles. Tossing his white-blond hair out of his eyes with a jerk of his head, Doug Foster had been the flesh-and-blood embodiment of them.

Doug had lived in the Coral Gables apartment complex behind the 7-Eleven where he worked and where they used to all hang out. He lived there with his mother and little brother. Lucy told her Doug had practically raised him. Kyle was thirteen, and when he wasn’t in school, he was with Doug, riding shotgun in Doug’s old blue Suburban and skateboarding in the 7-Eleven parking lot until Doug got off. Kyle was the reason Doug didn’t go to a lot of parties.

“That’s really cool,” Violet once said to Kyle after he flipped his board and landed on it. He’d glanced at her, startled that this stranger had talked to him, but said nothing.

Rumor had it their mother was a junkie. Violet had seen her at a pharmacy one afternoon; she’d been sitting in a chair—slouched, as if a teenager herself, freckled arms poking out from her diner uniform—waiting for her prescription to be filled. She was surprisingly small considering how large Doug and Kyle were. Violet had smiled at her, hoping to connect with this woman who lived with Doug, who touched his bed, clothes, body without thought, but his mother kept her head down, counting the bills in her wallet, then fixing her ponytail to hold the strands of hair that had come loose.

Doug didn’t talk much and, despite his popularity, often seemed uneasy. Or perhaps it was his popularity that made him uneasy. He never volunteered in Latin—the one class they had together—only speaking when called upon. Every morning before school, he studied alone at a back table in the cafeteria.

“Congrats on the Honor Society. I saw it on the board.” Grateful for something to talk about, Violet had finally gathered the nerve to approach him one morning. “Thanks,” he said. “You too.” She was so surprised he knew her name, that he’d noticed her placement, that she couldn’t think of how to respond.

He took his 7-Eleven job seriously and was fastidious about wiping down counters and straightening shelves. Some of the other football players had jobs, and they’d brag about five-finger discounts on CDs, athletic socks, and frozen yogurt, but Doug wouldn’t even take a penny from the take-a-penny-leave-a-penny dish. The few times he went to parties after games, he would get trashed—falling, slurring, passing out. In the following days, he would be even more subdued, seeming to go out of his way to avoid interacting with people, looking for excuses to go back into the stockroom. “He’s so mysterious,” Violet mused while sleeping over at her cousin’s house. “Just because he’s quiet doesn’t mean he’s deep,” said Lucy. “But he is totally hot,” she agreed. Do you think he would ever go out with a Black girl? Violet wanted to ask.

His girlfriend, Hailey Saunders, on the other hand, talked constantly, frequently punctuating statements with, “You know what I mean?” Except Violet rarely had any idea what Hailey was talking about. Hailey wore the long Laura Ashley dresses with drop waists that were in style, and Violet didn’t understand why a girl with a body as perfect as Hailey’s would choose to wear something so formless. But Hailey seemed to have the dress in every color and, with her purse hooked in the bend of her elbow and a set of gold bracelets on her wrist, she could have been a suburban mom running errands. Hailey’s hand would shoot up in class, her voice loud and certain. She’d smoke in the bathroom between classes, making plans for after-school mall trips with the rapt faces reflected in the mirror, her mouth not slowed even a little bit by the application of lip gloss and mascara. Violet wondered if that was Hailey’s appeal to Doug, her confidence and ability to fill space with noise. Well, that and that she would have sex with him—“If I’m gonna let him put his dick in my mouth, I might as well let him fuck me, you know what I mean?” Violet had never even let a boy finger her.

In the quad at lunchtime, Hailey once laughed so hard that soda came out of her nose, and everyone pretended to be grossed out. Violet hadn’t been aware she’d rolled her eyes until Lucy glared at her. She quickly recovered, asking Hailey if she could bum a drag off her cigarette. Hailey hesitated. “Okay, but don’t nigger-lip it.”

A couple of the girls gasped, and one said, “Hailey! Oh my God!” But Hailey’s friends were more entertained than scandalized. “What? I say it to everyone. You know that, right?” Violet nodded stupidly and took the cigarette from Hailey’s outstretched hand, burning with shame. She desperately willed her lips dry and barely touched the butt as she inhaled. Through the smoke, she saw the twins, Donna and Damien, two of the four Black kids at school, watching her from across the quad. They quickly looked away and gathered their lunch trash. Violet furtively brushed her thumb over the butt as she flicked it before handing it back to Hailey. “Thanks.”

At the first and last party Violet got drunk at—she’d previously been too scared to do more than take a few sips of a wine cooler—she ran out to the empty front yard to vomit and heard a girl yelling. Violet looked up to see Doug and Hailey sitting in his parked Suburban across the street. It was dark and there were no streetlights, but Violet ducked behind the tree she’d just puked under. Even in her state of nausea, Violet was thrilled that she might be witnessing their breakup. She never found out what had happened. The next day, her parents told her they were moving back to Lusaka.

Her father claimed they were going back so he could take care of his sick mother, but Violet knew he missed Zambia. Missed his family and friends, yes, but mostly the reputation he’d built over decades as a real estate developer—good tables in restaurants and complimentary bottles of wine, business favors, occasionally being recognized on the street. He missed being known. There were a few letters from Houston at first, well wishes and gossip in bubble cursive with hearts and circles over the i’s, but without a prospective reunion to warrant staying in touch, the friendships eventually lost steam.

Violet’s return to Lusaka was disorienting. Her father had lost a lot of money in poor investments, including their transatlantic moves, and had to rebuild his business after more than a year’s absence. Instead of the large Kabulonga house with a pool that she’d grown up in, her family moved into an apartment in Ridgeway. Instead of returning to the international school she’d previously attended, she took a bus to a government school, catching it from the market where her mother dropped her off on the way to the clinic where she worked. In the year she’d been gone, two of her closest friends had left to go to uni in the UK, one to boarding school in Harare, and another had moved with her family to the Copperbelt. In the one place that had felt like home, Violet now felt like a visitor.

Violet started smoking—for real, this time—and wearing eyeliner on the inside rim. She avoided the few Americans and hung out with a group of Form Five Zambian and Indian students—“The Crew” they unoriginally dubbed themselves—at the municipal sports club across the field from her apartment. They’d spike their green glass Sprite bottles with vodka, dancing to cassette recordings from Top of the Pops on someone’s boombox until half past five, when she’d race home to beat her parents’ six o’clock return. It wasn’t until Hiten teased her, “‘You know what I mean? You know what I mean?’ Of course I know what you mean; I speak English,” that she realized she’d been copying Hailey’s mannerisms.

She told her new friends about her boyfriend, Doug, back in Texas, detailing stories of weekends at friends’ ranches and water skiing at lake houses—activities she’d heard her Houston schoolmates talk about but that she’d never experienced. Thousands of miles and an ocean away, she could almost believe this relationship was real. There’s a Welsh word, hiraeth, that means to be homesick for a place you’ve never been, and Violet felt that—nostalgic for a relationship that had never happened. But time and distance make the heart forget, and Violet eventually had a first boyfriend (Brandon), a second (Hiten), a third (Brandon again), and when, the following summer, Lucy wrote with the news that two days after Doug left for Texas Tech, his little brother, Kyle, had shot himself, Violet was surprised by how quickly the grief faded for her first crush and the shy kid who’d made sound effects to accompany his skateboarding tricks.

Now, twenty years later, here he was, in Manhattan, standing outside Ollie’s Noodle Shop on Broadway. In high school, Doug had been burnished gold, his arm hairs sun-bleached against his perpetual tan. The man standing in front of her was pale and thin with dark circles under his eyes. But he wasn’t unattractive.

“You look the same,” he said.

“I wish,” she said. But Violet knew she did. She thought she looked better, actually, than when she was younger. She was thirty-five and starting to feel parts of her body shift, but she would joke with her friends that there was a portrait of her looking old as fuck in a hut somewhere in the Zambian bush.

They were blocking the entrance to the restaurant, and Violet gestured with her takeout bag for them to step aside.

“I don’t remember your name,” he said.

“Violet Chileshe. I hung out with Lucy Webber. She’s my cousin.”

Why was she explaining herself? He was the one who had stopped her.

“Do you live here? In the city?” Violet asked.

He considered her question. “For now.”

“I’m down on 85th. At Riverside? By the park?”

Jesus, why didn’t she draw him a map.

“Are you still in touch with anyone?” Violet asked.

“No.”

“Me, neither. Well, except Lucy, of course.”

He was big on eye contact, disconcertingly so. Violet didn’t remember this about him. No checking his phone, no glancing over her shoulder. Maybe he was on medication. He stood as if simple movements took great effort—arms hanging long by his sides, rooted legs. He looked tired.

“Are you doing okay?” she asked Doug.

“What do you mean?”

“I don’t know. I mean, what are you doing, what have you been up to?”

“I’m a botanist,” he said.

“Plants. That’s cool,” she said. He didn’t offer any more information.

Violet fought the urge to ask him another question and held up her takeout bag, “Well, it was nice running into you, but I need to eat before I go to work.”

“I just got back from Mars,” he said.

“The planet? Like, you’re an astronaut?”

“And a botanist.”

“Mars, huh?” she said. “That’s crazy.”

“It’s much safer than moon missions,” he said. Violet waited for him to smile, to break in some way, but his gaze was unwavering.

“I didn’t think people could go to Mars yet,” she said.

“You have a leak.”

Violet followed his gaze to the greasy, brown puddle forming on the concrete.

“Shit.” She held the bag out, but sauce had already splattered on her shoe.

She looked up at Doug. “Are you hungry?”

—

Violet lived in a rent-controlled apartment, the lease for which was in the name of a friend’s father. She’d previously been living on the Lower East Side with three roommates and two obese cats—one with urinary incontinence that resulted in the entire apartment smelling like cat piss no matter how often they cleaned—so when Aisha told her she was moving in with her boyfriend in Carroll Gardens, Violet had all her stuff uptown before Aisha had even finished packing. She and Aisha were both tall and thin, brown-skinned, with short, curly hair, and it seemed the other tenants were unaware that one woman had left and another had taken her place. She didn’t want to test it, though, so she never played loud music or had more than one person over at a time. If she got evicted, she would have to ask her parents for money, and her father would make their generosity a grand gesture to be brought up at every opportunity. She had yet to have her own name on a lease, yet to eat off of plates that she’d purchased, live in a place that she’d furnished—everything except for the bed had been left behind by Aisha. She wasn’t even sure what her style would be. Scandinavian? Bohemian? Shabby chic? She felt like all and none of them.

“So, how long does it take to get to Mars?” Violet asked.

She and Doug were sitting on the couch with enough space between them for a third person. (Doug Foster on her couch! Her fifteen-year-old self would have died.) Violet chewed an overly large piece of Hunan beef, feeling too awkward to take it out of her mouth now. When she had offered to share, Doug said he was a vegetarian and that he didn’t like spicy or ethnic food. He said nine years on a space station eating freeze-dried meals had killed any remaining taste for it, but Violet knew that he’d only eaten plain food before. At the 7-Eleven she once saw him get a hot dog and not even put ketchup on it. Another time, she’d stood at the Slurpee machine filling a cup she didn’t want so she could watch him while he microwaved a French bread pizza. He had rolled his neck from side to side while he waited, and she had desperately tried to think of something to say, but the machine ding!-ed before she came up with anything.

“Nine months.”

“Are you knocked out the whole time? Like in Alien?”

He smiled. “I wasn’t in a hyper-sleep chamber, if that’s what you mean. We work out a lot, actually. We’d lose too much muscle and bone mass, otherwise, and wouldn’t have been able to function when we landed.”

“What’s it like there?”

“In what way?”

“I don’t know. In every way, I guess. What does it look like?”

“It’s dusty and red. And hot. Like Arizona. Or how I imagine Arizona.”

“Were you scared you weren’t going to come back? I mean, if you were going to Mars you had to accept that you might not come back, right?”

He shrugged and kept his eyes on the wall in front of them. It was painted yellow, a design tip she’d read in a magazine—an accent wall is a great way to have a little fun! She’d immediately regretted the color but had been too lazy to paint over it. Doug’s breathing was audible, and now that they were inside, closer to each other and without the glare of sun, she could see that his hair was thinning. Or not so much thinning as gathering and puckering, like seersucker or the hair of an old cat. His temple vein pulsed blue through his skin. He didn’t seem dangerous. Then again, she figured she knew what dangerous looked like as much as he knew what Mars looked like.

“It sounds lonely,” she said.

Doug faced her. “The last time I bought my own food or clothes was more than ten years ago. I haven’t had to decide what kind of toothpaste or razor to buy. I’ve been back for a month and I still can’t walk down the aisles of a grocery store without becoming overwhelmed. There’s an entire section just for milk—cow milk, goat milk, soy milk, almond milk, oat milk. Where does oat milk even come from? Up there, I did my work and all other decisions were made for me. I was with a crew, but I haven’t had what anyone would consider real friends since before training. Or sex.”

“Are you asking me to have sex with you?” She tried to sound light. “Is this how astronauts flirt?”

“Sorry. I guess I’m still a little weird with social interactions. But I’d like to. I’ve thought about you.”

After all these years, Doug Foster had thought about her.

“I was kidding,” said Violet. “I didn’t know where you were going with that.”

She looked down at her bowl—chunks of celery, flower-shaped carrots, a couple grayish-pink pieces of beef with gristle. Oil had risen to the top, and she stirred it, trying to get the sauce to remix, but it was too cold now.

Violet stood and went to the sink, where she dumped the leftovers into a container to eat later. She felt Doug walk up behind her and held her breath. He turned her to face him. Ran his thumbs along her hairline. She closed her eyes as he rubbed along her jaw and over her lips. He leaned forward, his mouth and nose touching her neck, and inhaled. He did it again and then again until Violet grasped his head and gently pushed it away.

He pulled her blouse up and tried to lift it over her head, as if it were a T-shirt. “Wait,” she said. Violet undid the buttons, took it off, and hung it over the chair. The room was bright, filled with late-afternoon sun and floating dust motes. The blinds had fallen off a couple of months ago after a too-vigorous yank, and she hadn’t gotten around to fixing them.

Doug Foster’s tongue was skinny and long. It wasn’t sensual, but kissing him wasn’t unpleasant, either. She’d had years, decades even, of make-out experience but was unsure of what to do with her arms or how to angle her head. Doug’s hand slid inside her bra, pulling the fabric.

“Hang on. Let me take it off,” Violet said and reached her hands behind her. She had spent too much money on this bra to have him stretch it out. “Aren’t you going to take your clothes off?” she asked.

He looked down at himself like he’d forgotten he was even there.

He followed Violet into the bedroom and, while he removed his clothes, she opened the drawer of the bedside table and took out a condom. They lay down on her mattress on the floor. The pine boards of the Ikea frame she’d bought years earlier had cracked during the move, and the thought of replacing the bed, like fixing the blinds, like repainting the wall, had been too daunting.

They had sex, and his face was so open, his eyes so guileless, that she rocked her hips faster and avoided his gaze, instead watching the sun slide bars of light across their legs. He smelled of sweat mixed with Head & Shoulders, and Violet tried not to breathe in too deeply.

She had fucked Doug Foster. And the experience had been unremarkable. She felt—what? She wasn’t sure how she felt.

Doug pointed to a line on her bicep that divided darker skin from lighter skin. “You have this on both arms,” he said.

Violet held them up, side by side. “They’re my color lines. Or that’s what I call them. A lot of biracial people have them. And a birthmark at the base of the spine that looks like a bruise. See?” She rolled over so he could see it. “It’s called a Mongolian spot.”

“Why?” he asked.

“I don’t know. It just is.”

They lay on the mattress watching shadows sway against the wall. From this angle, it looked like she lived in a tree house, or at least had a yard. When you stood up, though, you could see there was only a lone, scraggly tree between her building and the one next door. Still, she lived in a one-bedroom on the Upper West Side. Maybe she’d stay here forever. She’d be ninety years old, death-gripping the railing with one claw hand and clutching Chinese takeout with the other, grease dripping on worn shoes she’d long ago stopped caring about.

“Hey, if you’re a botanist, any idea what’s wrong with my plant? I can’t figure out if I’m giving it too much or too little water.” She’d brought the ficus from her old apartment, and its yellow-streaked leaves were dropping daily.

“But why Mongolia?” Doug asked. “I thought you were from Kenya.” Kenya was always the go-to country for people who weren’t familiar with Africa.

“Some racist scientist probably named it after Mongolians, or something. I don’t know. But I’m from Zambia. My dad’s Zambian and my mom’s American. They live in San Francisco. They moved there about ten years ago. He’s a writer and she’s an oncologist.”

Violet’s father hadn’t written anything that she knew of beyond long, vitriolic mass emails about American and Zambian politics, but he and her mother always introduced him as a journalist. Since Violet also told people she was a writer, despite having only been published in two obscure online literary journals, she didn’t give them a hard time about it.

“You’re probably giving it too much water,” he said. “Or it needs a bigger pot. If roots don’t get enough air, they rot. What about you?”

“Am I rotting?”

He didn’t even humor her with a glance.

“I’m a writer, too. I’ve had some short stories published, and I’m working on a novel that my agent keeps hounding me for.” Okay, she didn’t have an agent yet, but the one she’d met at the bar where she worked had said she could send it to him when it was ready. She’d never advanced beyond entry level at any of her jobs, resistant to a future in an office building, to more responsibility, to conversations with coworkers she had nothing in common with besides their place of employment.

Violet rubbed her chin on his shoulder. “Doug? What have you really been doing? Where were you really?”

“On Mars. I told you.”

He looked pained, and she felt cruel for pushing it.

“Okay,” she said. The waning sunlight drifted into the corner. If she didn’t leave right now, she was going to be late for work.

“Hey,” she smiled. “I can finally say I had sex with Doug Foster.”

“What?”

“I had a huge crush on you in high school. So this is, like, a big win for teen me.”

Doug wrinkled his brow. “We hooked up in high school.”

“What are you talking about?” Violet covered her breasts with the sheet. “We never hooked up.”

He turned to her. “You really don’t remember? In that hotel. The one we stayed in during that snowstorm. For the away game.”

Violet stared at Doug. Finally, she barked out an angry laugh.

“That was Monica, you asshole. You fucked Monica Washington. Not me.”

Doug’s brow furrowed deeper as he thought about this. “No—”

“Un-fucking-believable.”

Monica Washington had been the fourth of the four Black kids at Forest Park: Monica, the twins—Donna and Damien—and Violet. Donna and Damien were dark-skinned, quiet, kept to themselves, and were generally regarded as the smartest students at Forest Park—past, present, and future. They both had 4.5 GPAs and had been accepted to Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale. Monica had been a cheerleader and, by what Violet came to assume was some sort of unspoken agreement between the two biracial girls, she and Violet never acknowledged each other, not even a nod or glance when they passed each other in the school hallways. In fact, it seemed to Violet that there was the mutual understanding to purposefully not talk to each other, as if to associate would make them stand out, would underscore their Blackness.

“Wow,” said Doug. “I don’t know what to say.”

Violet stood up and stepped over Doug, not caring that she was standing naked in daylight and he could easily see the stretch marks on her thighs, the dark hair that climbed up to her bellybutton. She grabbed her clothes and went into the bathroom. She didn’t want to put them on in front of him like they knew each other. When she came out, he was dressed and in the living room, standing by the front door with his hands in his pockets. He studied the floor and cleared his throat.

“I really thought it was you.”

Violet crossed her arms, pinching the skin in the soft spot.

“It doesn’t matter.”

“It does matter, though. I know who you are. Hell, you’re the reason I broke up with my girlfriend.”

“What do you mean?”

“That night at the hotel, we’d won the game and there was that snowstorm—and we never get snowstorms in Texas, not like that—and, for once, I felt like everyone else. I didn’t have to be poor, or look after— Anyway, I don’t want to make excuses, but I got wasted and I guess I got together with Monica. Who I thought was you for some reason. I’m sorry.”

Violet shook her head. “But what did you mean, I’m ‘the reason you broke up with your girlfriend’?”

“Nothing. It was a long time ago.”

“I want to know.”

He cleared his throat again. “After I told her we’d hooked up she, uh, called you a jungle bunny.”

“What?”

“She said since you were from Africa, you were, like, a real spearchucker or something. I don’t think she meant it; she was just pissed at me for cheating.”

“Is this supposed to make me feel better? That you broke up with her for being more racist than you?”

He was quiet for a moment. “I just wanted you to know that I knew who you were. Who you are.”

Violet looked at him and thought about telling him that she knew his mother was a junkie, that she’d heard she slept with guys for money, had even hooked up with some of the guys on the football team. She wanted to see his face when she asked if he was haunted by the image of his brother shooting himself in the head. If he’d been able to forgive himself for not taking his rifle with him to college or getting rid of it.

“I want you to leave,” Violet said.

“I really am sorry,” Doug said again.

“I have to go to work, and you need to leave.”

He nodded and opened the door. “I hope the writing thing works out for you, Violet. I hope everything works out for you.”

The lock clicked behind Doug Foster, and Violet listened to his footsteps fade down the stairs.

In the years after high school, she had been increasingly ashamed of how desperate she’d been to be accepted in Houston. The advent of social media had brought a few friend requests, but she’d deleted them all, wanting to forget these people who had witnessed her devaluation of herself. She occasionally looked up the twins, Donna and Damien; Donna was a petroleum engineer and still lived in Houston. From what she could gather, Damien was some sort of tech consultant in Silicon Valley. Violet also looked up Monica Washington, whose Instagram said she’d gone to Spelman College. She’d married and divorced, had two little boys and, according to her posts, lived a life filled with stylish Black women, cocktails, and island vacations. Violet sometimes hovered over the “follow” button on Monica’s page, but she couldn’t bring herself to push it.

Violet went into the bedroom to get her purse and saw the used condom in the trash bin. It had stuck to the side of the plastic liner. She twisted the bag to hide it and sat on her bed.

A leaf fell from the ficus, and Violet went to pick it up. To hell with this plant. She lifted the whole pot, realizing seconds too late that the bottom had disintegrated, and it dropped out. Dirt spilled across the floor, exposing a knotted ball of roots. Violet checked the clock on her bedside table. Shit. She was already twenty minutes late for her shift. She carefully cupped the nest with the broken planter bottom and took it to the kitchen sink. She got the Dustbuster and cleaned up the dirt in her bedroom. With the corner empty, the room felt open. Bigger.

Back in the kitchen, she picked up the plant to throw it away and saw that shards of terra cotta had stuck to the fibers. She pulled them off, careful not to break the pale strands. For the next hour, ignoring the repeated calls from the bar, Violet gently worked apart the coils, detangling the matted clump until all the roots were free. The poor thing had been suffocating.

Maya Perez’s short stories and essays have been published in American Short Fiction, Joyland, Electric Lit, Reflex Press, and others. Her screenplays have been recognized by fellowships from SFFILM/Westridge, Sundance Institute, and NY Stage & Film. Raised in Kenya, Zambia, and the United States, Maya now lives in Austin, Texas, where she teaches at UT Austin in the Radio-TV-Film Department.

You can purchase a copy of ASF Issue 72, in which Perez’s story first appeared, in our online store.