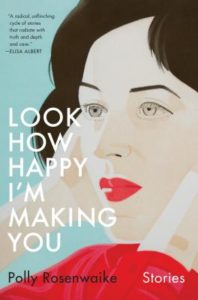

In her artfully constructed debut collection, Look How Happy I’m Making You, Polly Rosenwaike presents stories about motherhood, pregnancy, and the range of emotions that surround becoming—or not becoming—a parent. Rosenwaike expertly explores anticipation and excitement, loss and longing in twelve stories, which Kirkus calls “An exquisite collection that is candid, compassionate, and emotionally complex.” Here, Rosenwaike talks about her technique for capturing emotion on the page, writing what you would like to know, and finding inspiration from high school health class.

In her artfully constructed debut collection, Look How Happy I’m Making You, Polly Rosenwaike presents stories about motherhood, pregnancy, and the range of emotions that surround becoming—or not becoming—a parent. Rosenwaike expertly explores anticipation and excitement, loss and longing in twelve stories, which Kirkus calls “An exquisite collection that is candid, compassionate, and emotionally complex.” Here, Rosenwaike talks about her technique for capturing emotion on the page, writing what you would like to know, and finding inspiration from high school health class.

—

Nicole Beckley: I wanted to start by talking a little bit about the title: Look How Happy I’m Making You. Often it seems story collections take their titles from one of the stories. How did you decide on selecting a phrase, from the story “Grow Your Eyelashes,” as the title?

Polly Rosenwaike: None of the titles of the stories worked for the collection as a whole because they were too specific to the story itself, or they didn’t encompass the whole collection, or I just felt they weren’t exciting enough to be the title of the book. I wanted something catchy and unique that wasn’t going to be too sentimental, because writing about motherhood runs the risk of sentimentality. I wanted to hint at motherhood, but not mention it directly. I combed back through the book and thought maybe that line of dialogue in the first story might work. I like that it’s ironic; it gets at the idea that children do make you happy, but there are a lot of other emotions involved as well.

NB: What was your process of selecting the stories that ultimately went into the collection?

PR: I had written a few of the stories before I had my daughter, and then, about a year after, when I returned to writing fiction, I found myself writing stories about this period, related to experiences I had just gone through. I decided to lean into that theme and focus on particular moments in pregnancy and motherhood that I wanted to explore. It wasn’t quite a process of selecting stories for the collection, but more about generating stories specifically for it.

NB: Where do the seeds of a story start for you? Is there something you tend to latch on to first–a feeling, an idea, an image?

PR: All of those. The story “Field Notes” started with an image. When she’s in high school, the main character’s health teacher brings a fetus in a jar to class. That happened to me when I was in high school. My health teacher brought in this fetus for us to look at, and that image stuck with me for more than 10 years before I began writing the story.

With “June,” it was an idea first: what if a woman is pregnant with her first child, and at the same time someone she loves is dying, so birth and death are coming together for her in this difficult, which-is-going-to-happen-first, scenario. Sometimes a story starts from a phrase that I hear. The title of the last story is “Parental Fade.” I first heard that term when my partner and I went to the pediatrician for a sleep consultation for our baby daughter. That sparked a story for me about a couple sleep-training their baby, but the strangeness of the term also tapped into the larger empathic experience of having a child. I write a lot from just having an emotion that I want to translate into fiction.

NB: How long does it take you to shape a story? Do you work through a draft very quickly, or what’s your typical approach?

PR: I hardly ever work through a first draft quickly. In general it’s very slow, and I’m always returning to the beginning, shaping my sentences as I go through, because working at the sentence level is where I feel like I’m okay when the bigger picture feels insurmountable. To arrive at the final versions of stories took years in a lot of cases. I’m very much of the put-it-in-the-drawer-for-six-months school of not looking at something for a while and then trying again.

NB: A number of your characters do research professionally. How do you determine what professions your characters might have?

NB: A number of your characters do research professionally. How do you determine what professions your characters might have?

PR: It was important to me to display women’s jobs in this collection, partly because I enjoy working, but also because there’s this idea that becoming a mother takes over everything, becomes women’s primary identity, and I think that’s a problematic conception. Most of the women I know who are mothers of young children are also doing well in their professional lives. In terms of the characters’ jobs in the stories, a number of them are similar to jobs that I’ve had, like editing and teaching, but the most interesting ones were the jobs that I don’t actually know anything about. In “Field Notes,” Leah does research on cancer. I liked the idea of this woman who studies at the cellular level becoming pregnant and being fascinated by what’s happening inside her body, but at the same time feeling this isn’t the right time in her life to become a mother, and so she decides to have an abortion.

In “A Lady Who Takes Jokes,” Caitlin’s a cognitive psychologist. I did a little research on laughter and how children develop a sense of humor in order to figure out what she does. In that way, I was going by the principle of writing not what you know, but what you would like to know. When I was working on “Field Notes,” I asked my friend who was a researcher at a biomedical company to give me a tour of her lab. When it came to the cognitive psychologist character, I signed my daughter up for a study at a cognitive psychology lab. She was the subject, but I could secretly be taking notes on how they did their experiments.

NB: I was curious about how you handle the passage of time, and how the timeline of pregnancy might play into moving time in a story.

PR: I think that the pregnancy period is inherently dramatic. It’s building, it’s building—your belly is getting bigger. You know the baby has to come out, but there’s a lot of uncertainty around the whole thing. “The Dissembler’s Guide to Pregnancy” is structured around descriptions of pivotal moments during the nine months of the character’s pregnancy, at the same time as I’m trying to maintain tension about the dissembling aspect of it. The narrator keeps the secret from her sort-of boyfriend that she deliberately stopped taking her birth control pills. So I used that set passage of time in pregnancy alongside the relationship friction.

When I teach writing, I’ll often see that students feel like they need to include every moment in a story—to give a play-by-play of events. And then in other cases, stories suffer from the writer trying to cover too long of a time period in very broad strokes. One framework that I think is helpful is what Antonya Nelson calls “the story clock.” It can be anything you make it: a road trip, an event like a wedding, or a particular length of time. Your challenge as a writer is to figure out which story clock is going to suit your material, and also to signal to readers how the story clock is moving, so that they have a good sense of how the pacing is unfolding.

NB: In June you’re teaching a workshop with the Austin Bat Cave about writing emotion. How did you select that as a workshop topic?

PR: Inherently, that’s what I’m most interested in exploring in fiction. I think one of the intriguing things about writing is the way that we struggle to put emotion into language. Somebody cries, or their heart beats faster when they’re excited or anxious. These descriptions are often very clichéd, and they don’t really allow the reader to come in and feel, because it’s just sort of checking the boxes of what we think emotion in language is supposed to be. If you want to get emotion in a story, you often have to step back and make the atmosphere a little colder, so that the reader can bring their own warmth to it. Dark humor, subtle tension, understated language—these can be important means to allowing for that.

NB: That’s so interesting, I don’t know that I’ve ever thought about it as being a hot versus cold situation.

PR: The poet Kay Ryan compares it to holding an ice cube in your hand, how your hand warms the ice and melts it. So it’s that idea of bringing your warm human self to something that’s cold and painful.

NB: Are there specific writers who do a really good job capturing emotion on the page?

PR: Some of the stories I use in teaching include Amy Hempel’s “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried,” A. M. Homes’s “Do Not Disturb,” Eric Puchner’s “Beautiful Monsters,” and Edward P. Jones’s “The First Day,” which doesn’t employ that principle of coldness as much as the others do, but is just an incredibly moving piece of very short fiction. In my time as fiction editor at Michigan Quarterly Review over the past few years, we’ve published some great, emotionally rich stories by emerging writers—Jai Chakrabarti, Lindsey Drager, Hananah Zaheer, Rebecca Townley.

NB: When it comes to writing endings, is there something you write toward? Or how do you know when you’ve reached the end?

PR: I love endings. I think they’re my favorite part of writing. I often envision the ending early in the story, even if I don’t know exactly how I’m going to arrive at it. Middles are the most difficult for me. I usually have a sense of the beginning and ending of a story, but I’ve really got to work to create all the beats and necessary character development to get to that ending.

Polly Rosenwaike will be reading from her new collection at Book People in Austin on June 25. We hope to see you there!

Polly Rosenwaike has published stories in The O. Henry Prize Stories 2013, Glimmer Train, New England Review, Colorado Review, Iron Horse Literary Review, New Delta Review, and other magazines. She regularly reviews books for the San Francisco Chronicle; her reviews and essays have also appeared in the New York Times Book Review, The Millions, and The Brooklyn Rail. She has taught creative writing to college students at Eastern Michigan University and to elementary and middle school students through Seattle Arts & Lectures’ Writers in the Schools program and Hugo House. Currently, she serves as fiction editor for Michigan Quarterly Review and works as a freelance editor. Polly lives in Ann Arbor with the poet Cody Walker and their two daughters.

Nicole Beckley is a writer and performer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, 7×7, Tribeza, and the Onion AV Club, as well as in many small theaters and on at least one public access channel. She’s at work on a linked story collection titled Perfect Miss. She holds a B.A. in Urban Studies and Communications from Stanford University and currently lives in Austin, TX.