Hugo was a neighborhood debate. Ask me and I’d say, No, he wasn’t gifted from birth, wasn’t like Mozart composing with a finger up his nose and diaper rash on his ass. But mine was a minority opinion. To this day, people come to me and insist, with a passion I’ve only seen in late-night infomercials, that Hugo must’ve at least been born with the capacity to prophesize—the genetic musculature, so to speak. To which I say, Lower your voice, I agree.

Hugo was a neighborhood debate. Ask me and I’d say, No, he wasn’t gifted from birth, wasn’t like Mozart composing with a finger up his nose and diaper rash on his ass. But mine was a minority opinion. To this day, people come to me and insist, with a passion I’ve only seen in late-night infomercials, that Hugo must’ve at least been born with the capacity to prophesize—the genetic musculature, so to speak. To which I say, Lower your voice, I agree.

Listen: there are times in life when we know we’ve rubbed shoulders with greatness. So call him a sage, a soothsayer, prognosticator, guru; honestly, who cares? We were all Catholic around our grandmas but stayed devoted to Hugo’s fortunes twenty-four-seven.

His customers came from junior highs in Boyle Heights, City Terrace, Montebello, as far as Whittier. He took offerings in the form of back-pantry snacks, and in exchange, he’d pull out almost thirty pages’ worth of star maps, ascension coordinates, webs of compass-drawn circles, and charts of sunrise times that were recorded in sequences no one else could understand—never random, just too complex for simpler minds. Out of a second knapsack, he also sold dream catchers woven with horse-tail hair and necklaces made of decomposed road-kill bones and bowline-knotted shoelaces. Everyone I knew had at least one or the other.

Our next-door neighbor Luis was the neighborhood’s only true skeptic. He complained that Hugo’s predictions were either stupidly specific or ridiculously general—

You’ll be late for three things today, early for a fourth.

Take care not to miss the forest as you stare between the trees.

Whatever. They always came true.

Hugo drifted from street to street like he ruled the turf between Cesar Chavez and the 5, like it wasn’t gerrymandered every five minutes by White Fence, Breed Street, Evergreen, Tiny Dukes, and Mob Crew 13. Who knew if he was homeless? He looked younger than our parents, kept his hair short, and seemed to shower on the regular. That’s all the info we needed.

Most days he posted up at Hollenbeck Park, one block west and spitting-distance from our house on Chicago. A railroad hospital across the street had been abandoned in ’91. When the film crews weren’t swarming, my big brother Javi, Luis, and I would shortcut over the chain-link fence. Unless of course it was nighttime, which I don’t have to tell you is when the ghosts came around. Then we’d drag our asses down and around 6th.

For years, we’d see Hugo at least once a week.

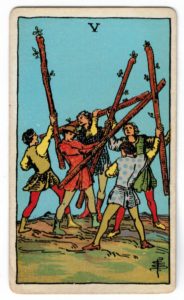

He’d sit cross-legged on the grass reading about the science behind Tarot, which he loved to debunk, or reclined against a hill slope, looking out over Hollenbeck’s oblong lake: the tall fountain that shot from its belly, dumb teens that hand-fed ballsy geese at its shore.

It was July the day Javi got fired from his first job. He was fifteen. Hugo lay bare chested, tattoos so sun washed his ribs looked bruised from a distance. As soon as he saw us coming, he brimmed a hand over his unibrow and watched us take seats on the grass. Whas good, kiddos? he said. ’Cept your skin Javi—that’s looked better.

Javi had been doing line prep at some downtown restaurant, where he’d chop, weigh, and wash these exotic vegetables with names he claimed not to know: some purple, some phallic, some that were probably fruits. Because of the butter and oils, his forehead caught the sun like a watch face and, at random, broke into miserable constellations, which I’d name things like Celibacy Major and Pizza Minor. He once asked if I thought he should wear a mask, then gave me the silent treatment when I said, You mean for work or like, out in public?

Javi rubbed his forehead. Luis turned to watch the small skate park on the far side of the lake, and without looking back I listened to the wheels that slid over concrete like chalk on blackboard. I could hear when joint lines in the ground jerked the sound into a gallop.

No no no don’t—stop touching your face, said Hugo. Rub toothpaste into your pores when you get home. Look, see? Never a blemish.

Good for you, said Javi.

From his Jansport, Luis grabbed an open Pop Tart box that we’d picked clean of everything but cinnamons, which we hated more than hunger. Hugo took the box from Luis, gently, using both hands. I love these, how’d you know?

Maybe I’m psychic, too.

Javi shoved Luis with his forearm. Mine was the first hand Hugo took into his. As usual, we both shut our eyes; I focused on the blades of grass poking through my pants; the wind sent me a whiff of Hugo’s woody, cedar smell.

Ok, I think I see. You, baby girl, are going to walk past a small sum of money, just minutes before its owner reclaims it.

Cool, I said, trying not to seem underwhelmed.

He took Luis’ hand next. Hugo didn’t bother closing his eyes; things came to him in an instant. Luis, you’ll find something—at home, I believe—that you didn’t even know you’d lost.

Luis sucked his lips and stared back. Then Hugo unwrapped a Pop Tart and bit off a bready corner, and Luis whispered to me: How’m I supposed to know if that shit comes true or not? Before I could tell him to shut up, Hugo cleared his throat and took Javi’s hand—stared at it, flipped it over, flipped it back, and pressed the palm to his heart.

Having a harder time with you. Let’s see. You—you—no, let me start again. Someday when you’re lying on your deathbed, Javier, you will be visited by the man you might’ve been.

Javi opened his eyes and then made it clear, when he opened them wider, that he’d deciphered what Hugo just said.

As soon as Luis lost it, I lost it. I usually kept it together around Hugo, but this time I was gasping silent laughs into the grass and Luis was clutching his stomach in genuine pain.

Who do you think it’s gonna be, Javi?

Mahatma Gandhi?

Wait, maybe the Pope!

How bout Babe Ruth?

The candy bar?

Muhammad fucking Ali!

Nah, nah—Bill Clinton!

Javi kept a stone face through all of it. But for years after—whenever he’d do something dumb or clumsy, like drop his toothbrush in the toilet or lose his house key—Luis and I would say, Neil Armstrong took better care of his toothbrush, or, Ray Charles never lost anything important.

Anessa Ibrahim is a fiction writer from Los Angeles. “Ray Charles Never Lost Anything

Important” is an excerpt from her novel-in-progress and was a finalist for the 2017 American

Short(er) Fiction Prize. She is currently an MFA candidate at the University of Minnesota. This

is her first publication.