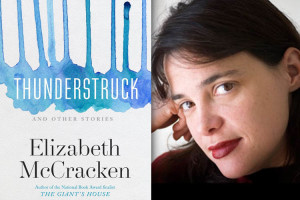

If, as George Saunders would have it, fiction is more interesting when death is in the room, then Thunderstruck and Other Stories, which won The Story Prize last week, is positively teeming with interest. Still, the various deaths and disappearances running through the nine meticulously crafted stories in Elizabeth McCracken’s moving and deeply cathartic collection could easily overwhelm if not for the charismatic force of her prose and darkly comic bedside manner. Where a lesser writer might dip into maudlin ruminations, McCracken makes space for morbid laughs and moments of unexpected grace.

Take this exchange from the penultimate story, “Peter Elroy: A Documentary by Ian Casey,” wherein the dying subject of the titular documentary is dumped off by his well-meaning wife at the home of his estranged friend, the documentarian whose film humiliated him and besmirched his reputation some three decades earlier. Casey has been suspiciously “called away on business” by the time Elroy arrives, and Elroy is left in the care of Casey’s much younger wife and small, precocious children.

“Can I get you anything, Peter?”’

“Glass of cold arsenic.”

“We’re out.”

“A glass of white wine, then.”

She looked at her watch. “Really?”

“Palliative,” he explained. He turned to the girl. “Can you do a wolf?”

“All right,” the Young Mother said dubiously, and left the room.

“Rawer!” said the girl, showing her little pointed incisors.

“Very good,” said Peter Elroy. “Extremely frightening.”

This same weary bleakness shot through with hard-won humor is all over “Juliet,” which boasts a wildly successful first person plural as the voice of a harried library staff shocked by the death of one of their many eccentric patrons, and “The House of Two Three Legged Dogs,” wherein a disillusioned English couple living in the French countryside scrapes desperately by with their houseful of abandoned animals and negotiates their feelings for their son, somewhere in England, set on selling their house out from under them.

Everywhere the living are haunted by the physical objects the dead have left behind. In “Something Amazing,” the aptly titled opening story, even sealing off the undisturbed room of a dead child can’t keep her ghost at bay.

The paint across the door is still tacky. It’s dumb to even be here. Joyce swears she can smell the fiberboard headboard of the bed through the barrier cloth, the scratch-and-sniff stickers on the desk, the old lip gloss, the bubble bath in containers shaped like animals arranged on the dresser top, the unchanged mattress, the dust. The dress from Bloomingdale’s that had been hers and then Missy’s, in striped fabric like a railroad engineer’s hat.

Likewise, the bereaved narrator of “Property,” whose recently deceased young wife—a German museum consultant who took ironic pride in her own lack of belongings—can’t outrun his grief. While she’d carefully arranged the everyday objects of Ezra Pound and Hans Christian Anderson, a duck shaped saltshaker with a chipped beak would be the sole exhibit in the museum of her, but it’s enough to devastate.

“The dead live on in the homeliest of ways,” McCracken writes elsewhere. “They’re listed in the phone book. They get mail. Their wigs rest on Styrofoam heads at the back of closets. Their beds are made. Their shoes are everywhere.”

The long title story that concludes this transcendent collection is a profound distillation of all of the darkness and worry that winds through the previous eight. It’s ends with a note of hope in the unfaltering faith of the father of a twelve-year-old girl existing in a liminal twilight between life and death after an accident in Paris has permanently damaged her brain and taken all he knew of her away, leaving only her body behind as permanent reminder.

McCracken, whose 2008 memoir, An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination, chronicled the still-birth of her own son, writes with authority and wit and a deep understanding of the ramifications of loss. These are sad stories; make no mistake—heady, intoxicating, and sometimes difficult, but always affecting, important, and fearlessly true.

Aaron Teel is the author of Shampoo Horns, one of five novellas in My Very End of The Universe, Five Novellas-In-Flash and a Study of the Form, and winner of the Sixth Annual Rose Metal Press Short Short Chapbook Award. His work has appeared in Tin House, Smokelong Quarterly, Monkeybicycle, Matter Press, North Texas Review, Art Prostitute, and Brevity Magazine among others. He is currently an MFA Fiction Fellow at Washington University in St. Louis