Carla felt sure she was the only rich girl to ever work the counter at Glazy’s Ham Depot. Carla hadn’t always been rich. Before Ed, she and her mom had once lived in a minivan for a year, so Carla remembered the ins and outs of being a have-not. Plus, her name was Carla, which was—at most— middle class. Her mother had chosen Carla before she’d understood the power of Margaret or Paige. Because of this, Carla could hold her own at Glazy’s. She parked her black Saab behind the Kmart. She left her Tag Heuer at home by the sink. Ed had gotten her the job because he owned the shopping center Glazy’s was in. He said every rich kid needed one poor job on the books. Carla could write her college essay about it, Ed said.

Carla felt sure she was the only rich girl to ever work the counter at Glazy’s Ham Depot. Carla hadn’t always been rich. Before Ed, she and her mom had once lived in a minivan for a year, so Carla remembered the ins and outs of being a have-not. Plus, her name was Carla, which was—at most— middle class. Her mother had chosen Carla before she’d understood the power of Margaret or Paige. Because of this, Carla could hold her own at Glazy’s. She parked her black Saab behind the Kmart. She left her Tag Heuer at home by the sink. Ed had gotten her the job because he owned the shopping center Glazy’s was in. He said every rich kid needed one poor job on the books. Carla could write her college essay about it, Ed said.

—

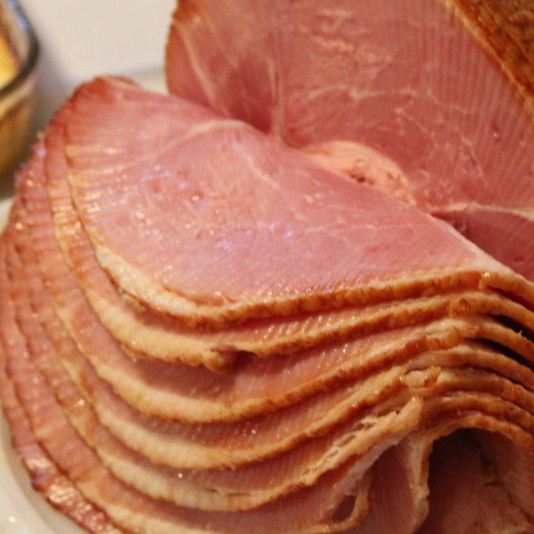

Glazy’s Ham Depot sold glazed hams. Carla’s job was to “reveal” them. She and Tammy and Sonya and Richelle worked the reveals and ran the registers. In the back, guys with blurry tats and small teeth slathered corn syrup, wielded blowtorches. It was almost Christmas. There were tinsel stars taped everywhere. Carla was back in Tennessee from her Rhode Island boarding school where, to her delight, all the boys looked like surfers in houndstooth, but, to her dismay, fucked like they were hammering nails. Richelle showed Carla how to pull back the foil from a ham and sell it.

“The foil’s your panties, the ham is your puss,” Richelle said. Richelle never smiled. “I sell the most hams.”

She pointed to the Employee of the Month pictures on the wall. There were eighteen of Richelle not smiling in her brown apron and brown hat. She had worked at Glazy’s nineteen months.

“Last April, I got an abortion,” she said. “It was Ricky’s. I loved him. Our names went good together. He cried during sex. He bought me a pink ice ring.” Richelle said ice like ass. “If I’d told him about the baby, he woulda made me keep it. But where am I gonna put a baby?” Richelle looked at Carla, unblinking. “Under the goddamn counter like a goddamn ham I’m gonna steal?”

Carla’s only takeaway was that she needed to meet this Ricky. She’d never heard of a guy like him. Ed talked stocks. Her missing father had talked shit. The boys at school didn’t talk at all. Where was this Ricky with his emotions and simulated jewels? Did he know his way around a florist? A Hallmark? A vagina? A heart? Carla knew she should be thinking about college, a career. Shopping centers. But Richelle’s story confirmed what Carla had suspected about herself all along: that she just wanted to be held, to have her hair brushed back from her face. Real estate wasn’t going to look her in the eye and call out her name.

“Did Ricky work here?” Carla asked.

“Naw,” Richelle said. “He worked the Valvoline.” Richelle folded back a portion of gold foil to reveal a flash of pink ham.

“I’ll take it,” a customer said. The customer was an old woman, not even a man. Richelle had talent.

—

There were four Valvolines in town. Carla took her Saab to all of them. She had four different services in four days. At every one, she asked coolly: “Is Ricky working today?” She had no plan if someone said yes. If Ricky was there, what would she say? Richelle told me about you? She needed to keep Richelle out of it.

At the fourth Valvoline, a guy named Gunther told her Ricky now worked the Sonic on Kildeen.

“That motherfucker can roller skate,” Gunther snorted. “You believe that?”

“Wow,” Carla said. “That’s something.”

Gunther looked at the Saab and frowned. “How you know Ricky?”

Carla stumbled in her head. “I sold him a ham.”

Gunther was okay with this answer. “Oh,” he said. “I like ham.”

—

Carla went to the Sonic three times before she found Ricky. He was short, even on skates, and had a shiny, spotted face. Carla watched him weave between cars. He could spin with a tray of food. She imagined his breath in her ear. She imagined him offering her a solitary rose. She saw him with a baby. He could calm that baby down. When Ricky brought Carla the milkshake, Carla looked him right in his eyes and pulled her V-neck sweater to one side to reveal the satin cup of her bra. Ricky’s eyes went big.

“Wait right here,” he said.

Carla watched him skate back inside. She watched him talk to someone, take o/ his hat and apron, skate back to the passenger side of her car. He got into the Saab with his big skates making a fuss of the floormat. He smelled metallic.

“I can take twenty,” he said. “I know a place.”

—

The place was a parking lot. Ricky kept his skates on. Ricky didn’t cry. Ricky could hammer a nail with the best of them. Maybe Richelle was a liar. Maybe this Ricky was the wrong Ricky. One thing was certain: Carla was still poor even though she was rich, and this Ricky was rich even though he was poor. When Carla dropped Ricky back by the Sonic nineteen minutes later, Ricky skated right out of the car and back to his hat and apron. He made it look easy.

—

The next day at Glazy’s, Carla parked her Saab right out front. She wore her Tag Heuer. On her co/ee break, she called around for the morning-after pill. For the rest of the day, Carla did what she always did. She took orders. She made change. She wiped counters. She brought out ham after ham from the warming racks. She peeled back corner after corner of gold foil. She revealed glimpses of pink to the customers. Sometimes the customers nodded and paid. But more often than not, they sent the ham back for a different one. Every time, Carla went to the warming racks and brought back the same ham and pretended it was a new one. Every time, the customers nodded and paid, satisfied.

Whitney Collins received a 2020 Pushcart Prize and a 2020 Pushcart Special Mention, and her story collection, Big Bad, won the 2019 Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. Her stories have appeared or are forthcoming in AGNI, The Pinch, Ninth Letter, Grist, Slice, The Greensboro Review, and Catapult’s Tiny Nightmares anthology, among others. “Ricky” was selected by Deb Olin Unferth as the winner of the 2020 American Short(er) Fiction Prize. Collins lives in Kentucky with her sons.