In 2016, there’s something almost anachronistic about creating a list of your favorite LGBTQ books. What kinds of books might qualify for such a list? Must the author identify as gay, bi, lesbian, trans, asexual, or agender to be included? In putting together such a list, don’t you run the risk of unintentionally ghettoizing “LGBTQ books” and further marginalizing authors? These are questions our editors and staff asked ourselves as we set out to celebrate Pride Month by building a list of book recommendations by and about LGBTQ people.

In 2016, there’s something almost anachronistic about creating a list of your favorite LGBTQ books. What kinds of books might qualify for such a list? Must the author identify as gay, bi, lesbian, trans, asexual, or agender to be included? In putting together such a list, don’t you run the risk of unintentionally ghettoizing “LGBTQ books” and further marginalizing authors? These are questions our editors and staff asked ourselves as we set out to celebrate Pride Month by building a list of book recommendations by and about LGBTQ people.

It was a process complicated by the horrifying shooting at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. That attack was all the more troubling because it targeted young LGBTQ people of color during a month when, in recent history, LGBTQ people have publicly celebrated their lives; lives that are constantly imperiled by individuals and systems that work to deny them rights, erase them from the record, threaten their livelihoods and, yes, murder them.

These recommendations, like any collection of recommendations from an arbitrary group of readers, are by no means comprehensive or definitive. What they are is personal, which is in any case perhaps the best way to approach any book by any person, regardless of label or category. They are presented in a spirit of solidarity with our LGBTQ loved ones, friends, colleagues, and fellow readers, and of admiration for their works. We will continue to celebrate writing by and about LGBTQ people every month of the year. For now, as June ends and we move into the second half of 2016, we hope that this list will introduce you to a new book or two, a new voice or two, a new perspective, maybe, and stories that speak to you as they have spoken to us, thus working that most magical of literary charms—connection.

—

Nate Brown, Managing Editor

Happiness, Like Water by Chinelo Okparanta

Chinelo Okparanta’s unadorned prose is the perfect vehicle for telling stories of family trouble, migration, tribulation, and difficult love that appear in her debut collection Happiness, Like Water. Okparanta’s sentences are direct and vivid, and in a story like “America,” in which the protagonist, Nnenna, is desperately trying to travel from her home in Nigeria to the United States where her beloved, Gloria, has gone, it’s that unflinching gaze that keeps the story from seeming sentimental. Instead of drippy romance, Okparanta offers a portrait of a sincere love that’s regretted by her family, shunned by society, and that endures anyway.

Favorite Passage:

“The sun is setting as I make my way down Walter Carrington Crescent. I look up. There are orange and purple streaks in the sky, but instead of thinking of those streaks, I find myself thinking of white snow, shiny metals reflecting the light of the sun. And I think of Gloria playing in the snow—like I imagine Americans do—lying in it, forming snow angels on the ground. I think of Papa suggesting that America would be the best place for me and my kind of love. I think of my work at the Federal Government Girl’s College. In America, after I have finished my studies, I’ll finally be able to find the kind of job I want. I think how I can’t wait to get on the plane.”

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

Few books have punched me so solidly in the gut as A Little Life, which isn’t to say that the book isn’t problematic. First, it’s more or less a novel about incredibly rich people who take their wealth for granted. Second, Yanagihara covers several decades without so much as mentioning broader changes in the culture, technology, entertainment, or social mores. Yanagihara elides details that would seem necessary to effectively tell a different kind of story; which is to say that the story she’s telling is so potent that the world-building undertaken in other long-form, large canvas works is unnecessary here. That potency resides in the excruciating suffering of her protagonist, Jude St. Fancis, and in the abundant, uncompromising love between Jude and his college roommate and best friend, Willem. Jude’s devotion to Willem and Willem’s devotion to Jude is, perhaps, idealized, but what better counterweight to immeasurable suffering is there than an ideal love?

Favorite Passage:

“He takes down the shirt he needs, a burgundy plaid woven through with threads of yellow, which Willem used to wear around the house in the springtime, and shrugs it on over his head. But instead of putting his arms through its sleeves, he ties the sleeves in front of him, which makes the shirt look like a straightjacket, but which he can pretend—if he concentrates—are Willem’s arms in an embrace around him. He climbs into bed. This ritual embarrasses and shames him, but he only does it when he really needs it, and tonight he really needs it.”

—

Maurice Chammah, Assistant Editor

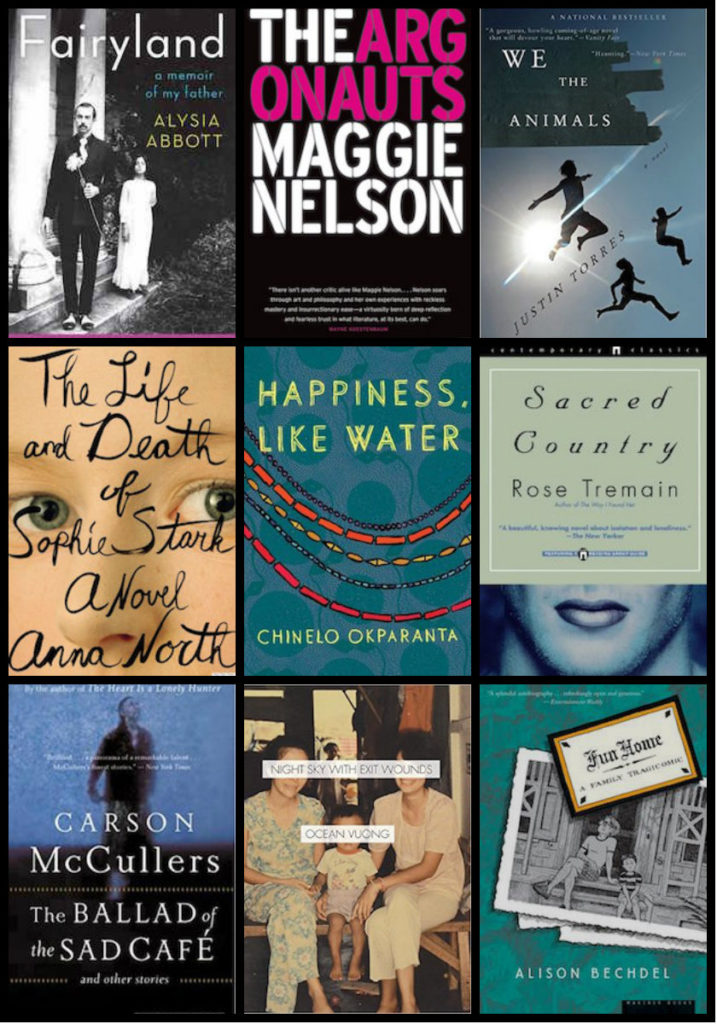

Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father by Alysia Abbott

This book has been on my to-read list ever since I read this vibrant excerpt published by Longreads last year. After her mother died in the early 1970s, Abbott moved to San Francisco with her father, who raised her in the city’s burgeoning hippie community, which included many recently-out men like himself. Drifting between apartments, she witnessed the birth of a rare and special time and place. As she grew older, many of the men she knew growing up, including her father, fell ill with AIDS. Much of her reconstruction of her earliest years comes from her father’s diaries, and she painfully confronts the decisions he made raising her.

Favorite passage:

“Reading about these events in my dad’s journals, it’s hard not to feel angry. My father expressed resentment because I asked him to fix me breakfast when, at age four, I was ‘perfectly capable of doing it alone.’ Maybe Dad couldn’t understand my needs because our life was populated by so many needy wanderers like himself, young people escaping bad homes and bad marriages, all searching for their true selves and open to anything that might further that quest: Hollywood, bisexuality, cross-dressing, meditation, Quaaludes, biorhythm charts, bathhouses, Sufi dancing. Renegades all, but few truly suitable for raising kids, let alone watching them for a night or two.”

—

Jennifer duBois, Contributing Editor

Sacred Country by Rose Tremain

Rose Tremain’s gripping and exquisite sixth novel follows the story of Mary Ward, a child growing up in rural England in the 1950s, who at the age of six realizes that he is a boy. Multiple characters narrate Mary’s twenty-eight year journey toward becoming the adult man Martin; the authority and lyricism of Tremain’s prose is matched only by the range of her empathetic imagination.

We The Animals by Justin Torres

Justin Torres’s debut is a sly, slim, elliptical barnburner of a book. Following three brothers growing up in upstate New York, the novel begins in a nearly choral group narration—out of which one painfully singular consciousness emerges. We The Animals is often gorgeous, sometimes terrifying, and always one-of-a-kind.

The Life and Death of Sophie Stark by Anna North

North’s powerful second novel tells the story of the enigmatic filmmaker Sophie Stark, a woman maddeningly devoted to art above all else. Told from the perspective of the friends, colleagues, and lovers who knew or tried to know her, Sophie Stark is a haunting meditation on what it means to truly understand another person.

—

Alexander Lumans, Assistant Editor

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

The Argonauts is a text of “autotheory” that tightropes between Nelson’s personal experiences (her pregnancy, her relationship with her fluidly gendered partner, and her own sexuality) and her critical eye toward our contemporary culture surrounding gender. The Argonauts takes its title from Roland Barthes, who refers to the legendary Argonauts as they preserved their Argo vessel by slowly replacing each piece of the ship over the course of their long journey, “so that they ended with an entirely new ship, without having to alter either its name or its form.” Drawing from a wide variety other writers, critics, and authorities, including Anne Carson, Judith Butler, and D.W. Winnicott, Nelson intricately reconstructs the Argo of her self-identity with the planks of others’ ideas and words. Yet she also often deconstructs herself and her theories, admitting to the limitations of this form: “I labor grimly on these sentences, wondering all the while if prose is but the gravestone marking the forsaking of wildness (fidelity to sense-making, to assertion, to argument, however loose).”

Favorite passage:

“How to explain—’trans’ may work well enough as shorthand, but the quickly developing mainstream narrative it evokes (‘born in the wrong body,’ necessitating an orthopedic pilgrimage between two fixed destinations) is useless for some—but partially, or even profoundly, useful for others? That for some, ‘transitioning’ may mean leaving one gender behind, while for others—like Harry, who is happy to identify as a butch on T—it doesn’t? I’m not on my way anywhere, Harry sometimes tells inquirers. How to explain, in a culture frantic for resolution, that sometimes the shit stays messy? I do not want the female gender that has been assigned to me at birth. Neither do I want the male gender that transsexual medicine can furnish and that the state will award me if I behave the right way. I don’t want any of it. (Beatriz Preciado). How to explain that for some, or for some at some times, this irresolution is OK—desirable, even (e.g., ‘gender hackers’)—whereas for others, or for others at some times, it stays a source of conflict or grief? How does one get across the fact that the best way to find out how people feel about their gender or their sexuality—or anything else, really—is to listen to what they tell you, and to try to treat them accordingly, without shellacking over their version of reality with yours?”

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

I recently learned about the Bechdel Test for movies. In order for a movie to pass the Bechdel Test, “(1) it has to have at least two women in it, who (2) who talk to each other, about (3) something besides a man.” This is indicative of Alison Bechdel’s fundamental concerns for the identity of women (and gender in general) in today’s society; moreover, this is the jet fuel that powers Bechdel’s investigations into herself. In Fun Home, her celebrated graphic memoir, she writes and illustrates about her own budding sexuality, about emotional abuse, and about the complex relationship with her father who committed suicide. Told in a recursive, labyrinthine manner that weaves together the author’s past, the author’s present, and the murky culture in which both take place, Fun Home navigates the mysterious waters of memory through visual and textual layering that is a sum total of artistry greater than its parts.

—

Rebecca Markovits, Co-Editor

The Master by Colm Tóibín

The novel is an intimate account of a period in the life of the masterful Henry James, beginning with the painful failure, in 1895, of his play Guy Domville—a disastrous attempt to break into the theater scene—and ending, five years later, at the verge of a new century, with Henry mostly withdrawn from public life and about to produce some of the greatest (and densest) novels ever written in English. Tóibín’s writing echoes James’s famous subtlety, but his sympathies lie nearer to his character and are warmer. He locates James’s detachment in part in his repressed sexuality, delicately detailing a complex and in some ways sad man whose turn away from the greater emotional demands of his life is a kind of failure, a failure that nevertheless contributed to the brilliant successes of his books. Tóibín has praised James for “the range of his sympathy and the quality of his prose . . . and for his deep understanding of the strangeness and the wavering nature of motive and feeling in human relationships.” All these strengths are firmly evident here, in his own beautiful novel.

Favorite passage:

A wonderful description of the difficult task of writing a novel: “The work would be at first like breathing on glass in its uncertainty and its delicacy; he would hope that he could see a pattern before the breath was cleared away. And then the labor involved would be rigorous beyond anything he had ever done.”

Maurice by E.M. Forster

Forster wrote this gay romance in 1913, but it was not published until after his death, in 1971. A note found with the manuscript read, “Publishable. But worth it?” The story recounts the coming-to-terms with his homosexuality of an otherwise ordinary, conventional middle-class Englishman, and how that “condition” ends up saving him from the banal confines of his class. The famous command in the epigraph of Howard’s End, “Only connect,” finds its resolution here in the love affair between the stodgy banker, Maurice Hall, and the working-class gamekeeper, Alec Scudder. The relationship is liberating on two fronts: Maurice is as much a critique of the constraints of England’s class system as it is about the human cost of its sexual mores. Forster insisted on the novel’s having a happy ending.

Favorite passage:

On the inside flyleaf of the novel, Forester wrote:

Begun 1913

Finished 1914

Dedicated to a Happier Year

It may be the ultimate “It Gets Better” sentiment, and reading it today, after a year in which this country witnessed both the first nationally-sanctioned same-sex weddings and the recent tragic violence in Orlando, it is impossible not to feel both the hope and the wrenching ache of those lines.

—

Erin McReynolds, Web Editor

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

In this short but dense but riveting book, the erudite and thorough luminary Maggie Nelson deconstructs gender identity as her body makes the transition through pregnancy by her also-transitioning transgender partner. This makes it sound far less poetic, moving, and important than it is—and by God! It is all those things. With sidebar citations of the philosophers, psychologists, and artists who inspire each bend of this journey (I wouldn’t dare call it “meandering” because, while it seems to lose itself happily in trains of thought, it always delivers the reader unto epiphany), you can’t help but feel you’ve become friends with the smartest girl on campus, that person who first opened your eyes to Foucault and Judith Butler, who turned your world on its head in the best possible way.

Favorite passage:

“You pass as a guy; I, as pregnant. Our waiter cheerfully tells us about his family, expresses delight in ours. On the surface, it may have seemed as though your body was becoming more and more ‘male,’ mine, more and more ‘female.’ But that’s not how it felt on the inside. On the inside, we were two human animals undergoing transformations beside each other, bearing each other loose witness. In other words, we were aging.”

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? by Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson‘s adoptive mother has to be, as critic Dwight Garner said, “one of the great horror mothers of English-language literature.” Winterson grows up in a northern English industrial town whose chilly darkness is as oppressive as her mother’s fundamentalism and hateful looniness. Against this backdrop, she struggles to find herself, through reading, through writing, and through a search for her biological mother. But her descent into madness reveals that accepting what one finds is the real and enduring struggle.

Favorite passage:

“The mind wants to heal itself—the psyche seeks coherence not disintegration. The mind then manifests whatever is necessary to work on the job. Going mad is the beginning of a process—it is not supposed to be an end result.”

Adeena Reitberger, Co-Editor

Ballad of the Sad Café and Other Stories, Carson McCullers

In Carson McCullers’s novel The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, she writes, “Maybe when people longed for a thing that bad the longing made them trust in anything that might give it to them.” This dangerous hunger conjures so much of McCullers’s work, including the seven titles in The Ballad of the Sad Café and Other Stories. The curiously lonesome characters in this collection love deeply, often unrequitedly. They flounder in ill-fated triangles; they teach themselves the science behind love, so they can fall into it at will, and with all the wrong things; they soften and then yearn for relationships too far gone. It is a beautiful collection about eccentric outsiders, helpless loners, and the brave and hazardous act of making oneself vulnerable.

Favorite Passage:

“I’m not explaining this right. What happened was this. There were these beautiful feelings and loose little pleasures inside me. And this woman was something like an assembly line for my soul. I run these little pieces of myself through her and I come out complete. Now do you follow me?”

— From “A Tree, a Rock, a Cloud”

Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Ocean Vuong

What else is there to say about this debut poetry collection that has not already been said? Vuong has the “ability to capture specific moments in time with both photographic clarity and a sense of evanescence” (New York Times), his “muscled intuition” (New Yorker) is “a gift” (Li-Young Lee), his book a “stunning introduction” (2016 Whiting Award) and exactly “what you’ve been hoping for” (Kenyon Review). Vuong’s poems are about subjects like war, family, childhood, love, and sex, and their quiet movement and clarity undulates, pulling the reader gently out to meet him. The places he takes you are heady, melancholic, and sublime. “Ocean,” he addresses himself—and maybe also the reader—in the final pages of the book, just before you leave his space and move back into your own, “get up. The most beautiful part of your body is where it’s headed. & remember, loneliness is still time spent with the world.” A tide of contentment. This grateful unbelonging, an invitation.

Favorite Passage:

“Say Surrender. Say Alabaster. Switchblade.

Honeysuckle. Goldenrod. Say autumn.

Say autumn despite the green

in your eyes. Beauty despite

daylight. Say you’d kill for it. Unbreakable dawn

mounting in your throat.

My thrashing beneath you

like a sparrow stunned

with falling. ”

—From “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous”

Stacey Swann, Contributing Editor

Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson

Though I first read Written on the Body almost twenty years ago, it’s never slipped off my list of favorite books. The plot follows the narrator’s love affair with Louise, a married woman, but the gorgeousness of the book is not really in the plot or in the fascinating way it refuses to reveal the gender of the narrator; it’s the language itself and its meditation on love that lit up my brain like no book before it. Though some critics found the vagueness of the gender irritating, it grounds the book in the idea that love—its beauty as well as the pain of its loss (the opening line of the book is “Why is the measure of love loss?”)—is the same maddening and mysterious emotion for everyone.

Favorite passage:

“‘Explore me,’ you said and I collected my ropes, flasks and maps, expecting to be back home soon. I dropped into the mass of you and I cannot find the way out. Sometimes I think I’m free, coughed up like Jonah from the whale, but then I turn a corner and recognise myself again. Myself in your skin, myself lodged in your bones, myself floating in the cavities that decorate every surgeon’s wall. That is how I know you. You are what I know.”

Where You Live by Jill McDonough

McDonough’s poems in this collection take us inside prison classrooms, bars after closing time, and backyards in Boston. There are poems about jokes (“Why are breasts like martinis?”), about love, and about war, all with such beauty and wit and empathy. What I love most are her poems that contain moments of connection with strangers, unexpected compassion and shared humanity in a world that can often lack both. When I’m feeling overwhelmed by intractable bad news, these poems are a consolation. (The end of “Accident, Mass. Ave.” makes me tear up every time.)

Favorite passage:

We aren’t offended, says Josey. We love you. Sometimes

I feel like we’re proselytizing, spreading the Word of Gay.

The cab is shaking with laughter, the poor man

relieved we’re not mad he sort of wants us dead.

The two of us soothing him, wanting him comfortable,

wanting him to laugh. We love our country,

we tell him. And Josey tips him. She tips him well.

— From “Three am”