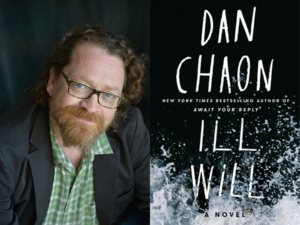

I first came to Dan Chaon’s work years ago via his celebrated story collection Among the Missing; even as a fledgling writer, I recognized that Chaon had the chops for beautiful writing and even greater empathy. Now, Chaon’s newest novel Ill Will showcases a multi-talented writer diving into the deep waters of emotional hazards and physical violence, all set against the backdrop of contemporary America, where our greatest fears and darkest truths lie just beneath the surface. Tonight, he will be receiving the Literary Star Award for Ill Will at American Short Fiction‘s “The Stars at Night” gala. I had the great pleasure of interviewing Chaon about his latest book as well as his approach to writing, experimenting, and American dread.

Alexander Lumans: In your novel Ill Will, there seem to be no significant characters who are solely good. Considering that you titled this novel something as dark as Ill Will, how conscious were you of creating this particular cast of morally flawed characters? What allows your “bad” characters to still be compelling?

Dan Chaon: I’ve always been fascinated by the line between good—>morally flawed—>bad characters and how we interpret them as readers. It’s a variable line, I think—just ask viewers of Dexter, or Breaking Bad. And it’s influenced by our shifting sense of identification and sympathy. I started out feeling like Dustin was the hero of the story, but he eventually became a much more compromised figure; I conceived of Rusty as a villain in the beginning, but I discovered, towards the end, a real sympathy and warmth for him. Ultimately, I think this is why we write—and why we read—to discover empathy where it didn’t exist before—and to discover antipathy, too!

AL: Alternatively, it’s been a long time since I’ve read a novel so centrally concerned with “happiness.” At one point, Dustin’s son Aaron describes him: “he looked like a guy who was pretty happy a couple of years ago and then had all the things he was happy about stripped away.” Do you think of “happiness” as a rich subject in its own right, or is it always meant to be shattered in good storytelling?

DC: Happiness is always a goal, I guess. I think that good storytelling assumes that every character has a different definition of what the term means, and in some ways knowing what makes a character happy defines them.

AL: You’ve mentioned in other interviews that you love writing exercises, and that parts of Ill Will came out of such exercises. Either in your generative or revision processes, did you have specific rules or goals for these sections that helped you craft and ultimately finish them?

DC: My rule is to get past the guardians at the gate. So much of writing is just about actually allowing yourself to write, giving in to the subconscious, shutting off the negative voices and allowing the story to emerge. I find timed writing very useful, and I’d send people to my friend Lynda Barry’s site: Nearsited Monkey.

AL: You employ several different formal trapeze acts in Ill Will: a variety of chapter sizes, shifting points of view, spacing on the physical page, sections and sentences cut off in the middle, even vertically fitting multiple narrative threads onto a single page. Obviously, form is important to you; you’ve previously mentioned Cortázar’s Hopscotch as a major influence. What role should form play in a text? What did you want to accomplish, via formal experimentation, in Ill Will?

DC: For me, formal experimentation is a way to present experience as it is lived—we need to figure out how to express an aspect of contemporary life that doesn’t yet have a form or language. I’m not interested in showing off. I just want to find an accurate way to portray things as they are experienced.

AL: In an interview you gave in Hobart, you mentioned that you love books with strong, propelling plots, but you said that whenever you tried to write plot yourself, you found yourself overcome with shame and then stopped. Yet Ill Will is an incredibly well-orchestrated, well-paced plot. Did expressly writing for plot play a significant role in writing this latest novel?

DC: In some ways, Ill Will is a bouquet to all the horror movies I watched in the 90’s and 00’s, to the serial killer novels I read obsessively, but also, strangely, the plot emerged as I went along. I realized as I was writing that much of the book was being written by my alternate brain, and that I didn’t have to “know” what was going to happen before it happened. It came together in the way dreams come together. Unbidden. That it seems “well-orchestrated” is particularly surprising. Plots are built into us, maybe.

AL: So let’s talk about American dread. Reading Ill Will, I definitely felt more than just twinges of Don DeLillo, Patricia Highsmith, William Maxwell, and Victor LaValle—all writers for whom the quintessential American experience is one of alienation, isolation, and fear. In a contemporary culture where the literary market thrives on police procedurals and woman-as-victim narratives, what is American dread to you and how do you manage to make it new in your work?

DC: I think we are in a condition now where our dread is fully managed by the machine. We are in a state of constant anxiety, but the locus is ever changing. Our fears are sold to us the same way everything else is, it’s targeted like advertising, and that’s the thing that’s new about it. In late capitalism, even our sense of doom is a commodity.

Alexander Lumans was the Spring 2014 Philip Roth Resident at Bucknell University. His fiction has been published in Story Quarterly, Gulf Coast, Cincinnati Review, Blackbird, and The Normal School, among other magazines. He received the 2013 Gulf Coast Fiction Prize, 3rd place in the 2012 Story Quarterly Fiction Contest, and the 2011 Barry Hannah Fiction Prize from The Yalobusha Review. He has received scholarships to Bread Loaf, Sewanee, and RopeWalk Writers’ Conferences. And he has been awarded fellowships to the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, VCCA, Blue Mountain Center, ART342, Norton Island, and The Arctic Circle Residency. He graduated from the M.F.A. Fiction Program at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.