They install the statue in our backyard, so we know how far we are allowed to roam without risk of pursuit. They plant it along the tree line, wielding chisels and pulleys. We watch from the window, the two of us, his hand on my shoulder. If you want me to explain the height of the statue, there’s the fact that my husband can stand under it for a bit of shade, and as you know, he’s quite tall. When I stand directly behind the statue, I disappear, and I’m quite wide these days.

They install the statue in our backyard, so we know how far we are allowed to roam without risk of pursuit. They plant it along the tree line, wielding chisels and pulleys. We watch from the window, the two of us, his hand on my shoulder. If you want me to explain the height of the statue, there’s the fact that my husband can stand under it for a bit of shade, and as you know, he’s quite tall. When I stand directly behind the statue, I disappear, and I’m quite wide these days.

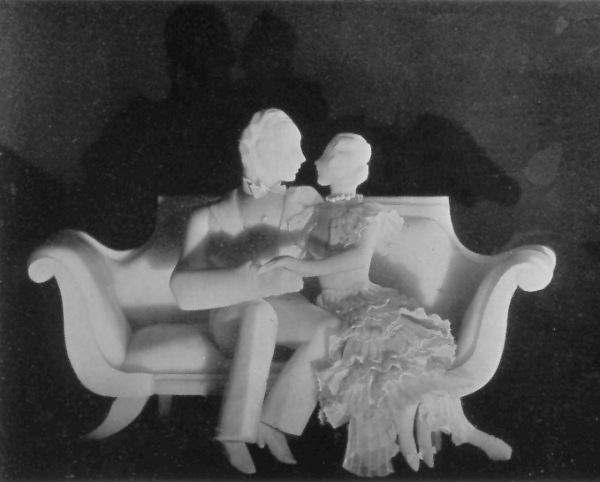

We build replicas of the statue in miniature, to poke fun at our incarceration. On the kitchen table, my husband leaves a small statue made of cheese, speared with a toothpick. I carve one from soap and use it to scrub the outer regions of his back, until it melts into the shape of a smooth, flat skipping stone. He fashions a mold and creates a more permanent series of statues from hot metals. We store them in a box under the bed, like a set of chess pieces, except every piece is the same.

One afternoon, they come to clean the structure on our lawn. They bring buckets of chlorine and large sponges. This is how we know we’re not going anywhere. My husband has an unrealistic obsession with escape, and I have my own struggles. Every morning I walk to my window, hoping for an unobstructed view. Every morning, the pedestrian crossing sign is still blocked from my line of vision. We are no longer pedestrians. We know what we’ve done.

He looks at vacation packages with unhealthy optimism. I leave a miniature statue on his stack of brochures, a threat, a paperweight reminder of our situation. He leaves a retaliatory statue on the book I’m reading, the one about giving birth in captivity. I place a statue on a pillow between us in bed, the sharp side pointing up. After a particularly eviscerating fight, I leave a stray statue on the stairs, positioned perfectly for tripping. I think better of this before it’s too late. I’m learning to consider my actions. Really, I am.

I’m sure you’ve heard of the legendary captive who dressed in a statue costume and planted himself on his neighbor’s lawn. He went unnoticed for a full month after his escape, standing perfectly still. How did he scratch his nose? This is one of the questions. I’m sure you’ve also heard what happened to him, next.

My husband and I stop exchanging words in favor of exchanging statues. If he cries, I place the cool metal in his palm. If I laugh, he arranges the statues in a circle around me to prolong and protect the laughter. Even as he packs the essentials for his escape, and dresses in his best disguise, I stand before him silent, dense, and sturdy. I tuck a cluster of our totems in his overnight bag. Their little faces, so forbidding.

Hilary Leichter‘s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Southern Review, n+1, Tin House, Electric Literature, The Atlas Review, VICE, The Kenyon Review, the Indiana Review, and elsewhere. She is a contributing editor at NOON, and a recipient of fellowships from The Edward F. Albee Foundation, the Table 4 Writers Foundation, and Columbia University. She is currently working on a novel about an auction house.