In this weekly series, Intern Alyssa, your fearless reader, will review popular short stories and their film adaptations. We’ll explore what works in each medium and what doesn’t and how exactly the allure of literature can translate to film. Alyssa has no formal training in film, unless subscribing to Netflix and following Roger Ebert on Twitter count as formal training. She would also like to issue one big standing Spoiler Alert now.

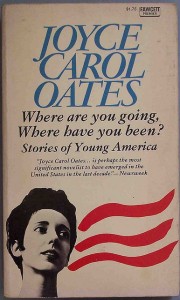

In 1966, twenty-three-year-old Charles Schmid was convicted of killing three girls in the Arizona desert. Schmid, the “Pied Piper of Tucson,” caught the attention ofTime, Playboy, Life—and Joyce Carol Oates, who based her 1966 short story“Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” on Schmid’s murders. Oates’s oft-anthologized story, first published in Epoch Magazine, tells the story of fifteen-year-old Connie’s sexual awakening…sort of. Rebellious and beautiful, Connie spends the summer before her sophomore year of high school sneaking off to a drive-in to flirt with boys. One of those boys, though, turns out to be a creepy older man with the creepy name “Arnold Friend”—and the creepy habit of stalking teenage girls. When he shows up at Connie’s house while the rest of her family is out for the day, he verbally terrorizes her until she “gives in” and leaves her house with him.  Oates’s story is many things: an allegory, a coming-of-age tale, a psychological horror story. I remember reading this story in college and feeling a vague sense of déjà vu, and I wondered if I had read this story before, or if it just eerily tapped into one of my greatest fears as a teenager. Whatever your interpretation, it’s a very effective story. One of the ways in which I think Oates succeeded especially is in establishing a sense of Connie’s isolation, thanks in part to the allegorical ambiguity of the setting and characters. Connie inhabits a nightmarish fairy tale, replete with a cruel mother, a plain but perfect sister, a spectral father, and a golden carriage Cadillac. The structure of the story enhances this somnolent sense, with several sleepy paragraphs of prose describing Connie’s daydreamy life before her final encounter with Arnold Friend. Indeed, on the afternoon that Arnold shows up at her house, Connie awakes, disoriented, from a nap:

Oates’s story is many things: an allegory, a coming-of-age tale, a psychological horror story. I remember reading this story in college and feeling a vague sense of déjà vu, and I wondered if I had read this story before, or if it just eerily tapped into one of my greatest fears as a teenager. Whatever your interpretation, it’s a very effective story. One of the ways in which I think Oates succeeded especially is in establishing a sense of Connie’s isolation, thanks in part to the allegorical ambiguity of the setting and characters. Connie inhabits a nightmarish fairy tale, replete with a cruel mother, a plain but perfect sister, a spectral father, and a golden carriage Cadillac. The structure of the story enhances this somnolent sense, with several sleepy paragraphs of prose describing Connie’s daydreamy life before her final encounter with Arnold Friend. Indeed, on the afternoon that Arnold shows up at her house, Connie awakes, disoriented, from a nap:

…when she opened her eyes she hardly knew where she was, the back yard ran off into weeds and a fence-like line of trees and behind it the sky was perfectly blue and still. The asbestos ranch house that was now three years old startled her—it looked small. She shook her head as if to get awake.

You know how sometimes when you’re dreaming, you think you wake up, but you’ve only woken up in the dream? Everything seems almost normal, except you have this nagging thought that your cat isn’t supposed to be talking, and your house doesn’t have eighteen flights of stairs, and James Franco isn’t actually your boyfriend. That’s how the rest of the story feels: like a bad dream from which we’d like Connie to wake. As Arnold threatens and coaxes Connie out of the house, she becomes more and more disoriented: she no longer recognizes her house, and she dissociates until she feels she is watching herself open the door and leave the house. Whereas lengthy, languid paragraphs occupy the first third of the story, Arnold Friend’s unnerving dialogue makes up the majority. Near the end, Connie tells him, “People don’t talk like that, you’re crazy.” Although Arnold doesn’t physically violate Connie (on the page, at least), his verbal assault is enough to make me cringe and want to look away. It’s incredibly disturbing, and Oates succeeded most in her fearlessness with his character.

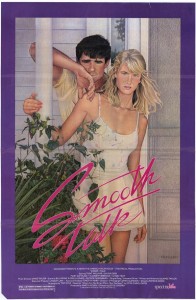

Smooth Talk, Joyce Chopra’s 1985 adaptation of Oates’s story, succeeds largely thanks to its cast and its screenplay—though it doesn’t always go as far as I’d like it to. Laura Dern’s portrayal of Connie is subtle and endearing, and Treat Williams lends to Arnold not just a convincing creepiness but also a disturbing charm. (Mary Kay Place is also great as Connie’s ambivalent mother.) I found the structure of the movie really interesting. At just 92 minutes, it’s on the short side, and a full two-thirds is exposition of sorts: Connie fighting with her mom; Connie and her friends at the beach, at the mall, at the drive-in. Laura Dern is so charming that I enjoyed watching all of these scenes, even if the extras and the score evoked ABC after-school-specials. I suppose it would be difficult to market a movie that’s just an hour of Treat Williams being creepy, and I like Chopra’s choice here. Tom Cole wrote the screenplay, which takes lines verbatim from the story—notably Connie’s mother complaining about Connie’s “trashy daydreams,” a phrase I was happy he used. My biggest complaint with the script is that I don’t think Cole went as far as he should have with Arnold’s dialogue. Although Cole’s Arnold is certainly threatening, he didn’t inspire in me quite the same sense of fear and imminent danger as Oates’s Arnold did. For example, Cole modifies this pivotal line: “I’ll have my arms tight around you so you won’t need to try to get away and I’ll show you what love is like, what it does.” Um, that line alone makes me want to make sure all my doors and windows are locked (they are), even though I’ve read it a million times. In the movie, it’s the still frightening (but somewhat less so), “I’ll hold you so much and tight you won’t need to think about anything or pretend anything and you won’t even want to get away, even if you’re scared.” Similarly, he doesn’t explicitly threaten her parents. imagine the slight softening of Arnold is due to Chopra’s decision to modify the ending of Oates’s story. In Smooth Talk, the viewer sees that Connie makes it out alive, so that the movie ends up feeling like a bit of a morality play: this precocious teenager is punished for daring to explore her sexuality. I find that disturbing, especially in light of the final scenes of the movie, where Connie makes amends with her family and dances with her sister to James Taylor’s “Handy Man,” a callback to an earlier scene in the film. “You wouldn’t feel, like, defiled or anything if I touch you?” Connie asks her sister. She’s smirking, but we know she means it. “Do you still like this song?” she asks her sister a minute later as they dance. It’s a telling, honest moment that reveals the way Connie feels changed after her encounter with Arnold, but the lack of commentary with which it’s presented complicates it for me. Joyce Carol Oates wanted nothing to do with the adaptation, but she praised it once she had seen it and even defended Chopra’s new ending. I thought it was a successful adaptation, too. Like its source material, Smooth Talk is enjoyable, disturbing, complicated, and thought-provoking—even if it does have lots of cheesy synth music. Stray observations:

- Charles Schmid was a gymnast, and Treat Williams does some neat little balancing beam acts on that gold Caddy of his. Not sure if those facts are intentionally related.

- Joyce Carol Oates dedicated the story to Bob Dylan, whose song “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” inspired the title.

- Do you need a creepy Halloween costume idea? You should go as Arnold Friend. He stuffs his boots to make himself appear taller, so you’d be totally comfortable walking around all night.

- Smooth Talk, which no one I know has ever heard of, won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance the year it was released.